Let Fury Have the Hour - Shelley and The Clash

Let Fury Have the Hour - Shelley and The Clash

On 8 May 1970 the Beatles issued their final album and broke up - the music that I had grown up with was, I thought, finished and the world was unraveling. Ah youth. I was not yet 16. Then, when I was barely 18, the chess and hockey started - and things really went nuts.

In the summer of 1972 the American Bobby Fischer faced Boris Spassky, a Russian, in a chess (chess!!!!) match that came to be known as the “Match of the Century”. It dominated newspaper headlines for months. Without question this will be looked back on as the most famous chess match ever played - though not necessarily because of the chess - though it was brilliant. Garry Kasparov, a subsequent world champion, explains why:

“I think the reason you look at these matches was not so much due to the chess factor but rather the political element. This was inevitable because in the Soviet Union chess was treated by the Soviet authorities as a very important and a useful ideological tool to demonstrate the intellectual superiority of the Soviet communist regime over the West. That is why Spassky’s defeat was treated by people on both sides of the Atlantic as a crushing moment in the midst of the cold war”.

“Then the chess and hockey started - and things really went nuts.”

Spassky (left) and Fischer in 1972

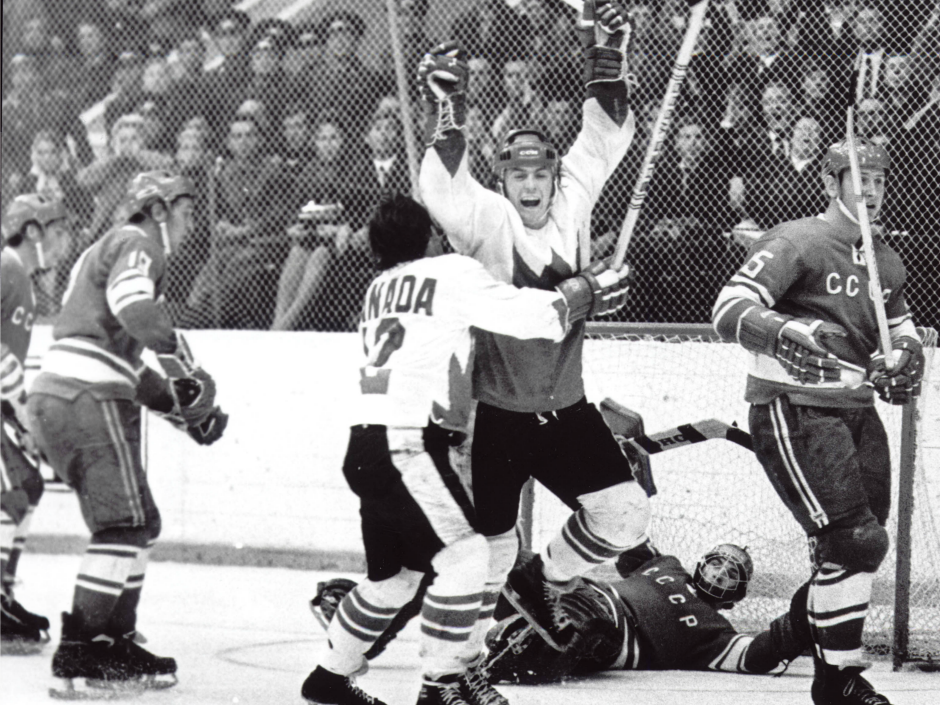

Spassky had barely resigned the match on 31 August 1972 when a mere 2 days later a very different and far more physical cold war contest began. On 2 September 1972 Canada and the Soviet Union squared off in what came to be known as the Summit Series. For decades the Soviets had dominated international hockey largely because the Canadian had never “iced” their professional players. For the first time, our best would face their best. 26 grueling days later the series ended with a dramatic last minute goal - Canada had defeated the Soviet Union. I know exactly where I was.

In that same summer, the Black September terrorists kidnapped and murdered Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. Then came an oil embargo that roiled the world. Next came Nixon’s epic disgrace and resignation. Over the next few years we would learn about the deaths of millions of Cambodians at the hands of the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot. During this same period wars erupted across Africa as former colonial states fought for independence in places like Rhodesia and South Africa.

In 1978 we were shocked by the mass suicides in what was called Jonestown. We were also introduced to the concept of serial killers thanks to the predations of David Berkowitz (the “Son of Sam”) and Ted Bundy. The threat of nuclear disasters also dominated our world culminating in Three Mile Island accident in 1979. The soundtrack for much of this period was a bizarre mishmash of “prog rock” and disco. Below the surface, however, we took shelter with Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith and holdovers from the late 60s.

Paul Henderson scores the winning goal with seconds left.

I am not going to suggest that the 1970s were uniformly terrible. Every era has its good and its bad. The chess was terrific and Canada’s national hockey team accomplished what was thought to be impossible. Mother Theresa won the Nobel peace Prize. Arthur Ashe won Wimbledon. Hank Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s home run record. Louise Brown became the world’s first test tube baby. Secretariat blew away the field to win the Triple Crown. Billie Jean King beat that fool Bobby Riggs. Some amazing movies got made: Clockwork Orange, The French Connection, Chinatown, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Taxi Driver, and Alien. And musically, the decade went out in a blaze of rock and roll we called punk.

Somehow, during all of this confusion, I managed to come of age and become a man. I graduated from high school in 1973 and eventually went to University. I fell in love, out of love and back in love. I cemented friendships which have endured to this day. But what sustained me for the latter part of this decade was a couple of things: my love of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s and music - specifically, punk rock.

“ Let fury have the hour, anger can be power - The Clash”

I was young and fairly revolutionary in my thinking. I was studying English literature - Shelley and Blake were my heroes. I liked them because they opposed the status quo - they fought the system. Much like Shelley, I could not abide Wordsworth - not because of the poetry - but because he became a backsliding, reactionary, counter-revolutionary. He became as, Mary Shelley so succinctly put it, a “slave”. And there is nothing that youthful rebels despise more than seeing their heroes back-silde into conformity.

In the 1970s, Shelley was still an outcast in the academic community – his reputation had been almost irreparably damaged by the likes of Eliot and Leavis. It was only just then in the process of being resuscitated thanks to scholars such as Milton Wilson (with whom I had the luck to later complete my masters at the University of Toronto), the great Kenneth Neill Cameron and Eric Wasserman. To study Shelley was almost an act of rebellion in and of itself. He was a lot of very cool things: atheist, vegetarian, philosophical anarchist, feminist, anti-monarchist, republican and lots more. He was seriously rock and roll.

One of my favourite bands from the era was Buzzcocks, an English outfit fronted by a man named Pete Shelley. Pete had been born as Peter McNeish; but when he took to the stage he changed his name to honour his favourite romantic poet. I was enthralled by this idea and when I wrote my masters thesis, I included three musical epigraphs: two from the Sex Pistols and one from Buzzcocks. It was perhaps a stretch - however in my youthful rebellious mind I thought it was apt.

But was it really so far-fetched to tie together punk music and romantic poetry? To test this, I thought I would be fun to have a quick glance at one of the classics of the era to see if there are, in fact, any Shelleyan overtones. That classic? Clampdown by The Clash from the album London Calling. Let’s dig in.

To make this work, you really need to do me a favour. You need to follow this link or this one or this one and give the song a few listens. When you are done that, come on back and let’s continue.

Clampdown is a song about the loss of youthful ideals. Written by Joe Strummer, one of the band's most fiercely anti-establishment members, the song charts the manner in which this can happen. And just as Shelley understood importance of language, so too did Strummer. He laments the manner in which society teaches its "twisted speech to the young believers"; the manner in which youthful revolutionary instincts are dulled by an inculcated appetite for money and the acquisition of luxuries.

We will teach our twisted speech

To the young believers

We will train our blue-eyed men

To be young believers

“You grow up and you calm down - you’re working for the clampdown. - The Clash”

The tendency of revolutions to fail to bring about meaningful change and progress was always a concern for Shelley; it is one of the reasons I think he was almost obsessed with language. I am not sure that, apart from Shakespeare, there has ever been a writer who not only understood the power of language, but who mastered it so completely. Words can free us; words can enslave us. Professor Michael O’Neill in his keynote address to the Shelley Conference 2017 digs into how Shelley uses language to challenge custom and habit; or, as O’Neill puts it, to "invite [his readers] to reconsider the world in which we live." This, to me, strikes at the heart of Shelley’s entire output; this was a man who believed that poetry (or more generally cultural products) could literally change the world. I have written about this here and here.

In the case of Clampdown, Strummer castigates the youth of all generations, alleging, "You grow up and you calm down / You're working for the clampdown. For his part, he imagines a revolutionary resistance to the state:

The judge said five to ten-but I say double that again

I'm not working for the clampdown

No man born with a living soul

Can be working for the clampdown

How familiar does this start to sound? I hear echoes of Prometheus facing down the Jupiter in Act 1 of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. Both speakers see themselves as martyrs. In Clampdown, the protagonist is charged by the police for an act of rebellion against the state. At his trial, he defies his judge and asks for his sentence to be doubled. Then, spitting with anger:

Kick over the wall cause governments to fall

How can you refuse it?

Let fury have the hour, anger can be power

D’you know that you can use it?

“Kick over the wall cause governments to fall. - The Clash”

The state, however, is seen as cunning and subversive. It gets inside your head, it coerces you subtly; wears you down, urges conformity. Why fight the system? You will never win. At this point I hear the furies from Act 2 of Prometheus Unbound taunting Prometheus. Strummer himself imagines a subversive internal dialogue that erodes the will to resist:

The voices in your head are calling

Stop wasting your time, there's nothing coming

Only a fool would think someone could save you

Even the members of one's own class are not to be trusted:

The men at the factory are old and cunning

You don't owe nothing, so boy get runnin'

It's the best years of your life they want to steal

He then moves to the accusatory crescendo of the song:

You grow up and you calm down

You're working for the clampdown

You start wearing the blue and brown

You're working for the clampdown.

“Shelley was a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism - Marx”

Joe Strummer

And once this happens the conversion is complete. Youthful rebellion is replaced by aging complacency and conformity - the young rebellious Wordsworth becomes the old reactionary Wordsworth. The revolution, in other words, fails. It seems to me that there are some surprising echoes here of both Prometheus Unbound and Shelley's own life. The voices inside Joe Strummer’s head are the Clash's version of Mercury and the Furies. We all hear them. Unlike Shelley, however, Strummer had no real sense of the perfectibility of man. He saw only chaos and degradation – the endless cycles of revolution-tyranny-revolution. Shelley saw a way out. Not so Joe Strummer.

Shelley, drawn by Edward Williams (If only PBS had a publicist!)

As a young man, despising Wordsworth as a sellout and extolling Shelley as a revolutionary, I clung to the message of Clampdown: which I took to be: "Don't grow up and turn into your old man; don't conform." Be Shelley, not Wordsworth. Now, of course, there was one flaw in my thinking. Shelley died before he had a chance to turn into a Wordsworth; before the voices in his head subverted his revolutionary impulses. And he has detractors who suggest that had he not died, this is exactly what would have happened - he would have grown up and become a proper Tory.

Possibly. But maybe not. Not everyone is destined to become a Wordsworth. Think for example of the great crusading journalist (and Shelleyan) Paul Foot. I wrote about him here. Or what about Ursula Leguin (another Shelleyan). Leguin and Foot never for a minute surrendered their ideals. I like to think Shelley would never have surrendered them either, would never have worked for the clampdown. And I am not alone, here is what Karl Marx said:

"The real difference between Byron and Shelley is this: those who understand and love them rejoice that Byron died at 36, because if he had lived he would have become a reactionary bourgeois; they grieve that Shelley died at 29, because he was essentially a revolutionist and he would always have been one of the advanced guard of socialism."

But those voice in our heads........they keep calling - don’t they. Shelley knew that. Contrary to what many think, Shelley was not a utopian and Prometheus Unbound is not his vision of utopia. Have a close look at Act 3. After the forces unleashed by Demogorgon oust Jupiter, Demogorgon does not vanish - Shelley envisages that he retires to a cave beneath the world from whence he may be called forth again in the event the revolution fails. This underscores Shelley’s lifelong skepticism: you can fight for change, you can win, but you can just as easily lose everything you have gained down the road. The only cure? Eternal vigilance and an ever-renewing revolutionary imagination.

The rebellious spirit of the romantic poets is really not so far removed from that of the punk rock musicians of the 1970s and 80s. This is why the study of poets like Shelley (in particular) can offer so much to us today. There is a commonality of spirit, a sort of intellectual esprit de coeur, that unites them - that unites are true revolutionaries. And they all tell us one thing: we grow old at our own peril.

“Let fury have the hour, anger can be power”.