Guest Contributors

My goal when I established this site was not just to afford an outlet for my own writing on various subjects, but also to draw attention to what others have to say. I hope that every week I will be able to offer readers fresh ideas and perspectives not only by poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, but also those in his circle: Mary, Claire Clairmont, Byron, Keats, Leigh Hunt and others.

What Shelley Means to Me

Allow me to introduce you to Oliver. Oliver popped up one day on my twitter feed. Oliver’s pronouns are they/their and they are a high school student living in Michigan. Oliver has an incredible passion for poetry and Shelley in particular. Oliver started asking for book recommendations - and they devoured them. They started doing research and bringing new findings and perspectives to our twitter feeds. Oliver started engaging with a large cross-section of the online Shelley community - ranging from amateur fans to some of the most respected academic authorities in the world!

Shelley in a Revolutionary World

There’s something in the Romanticism of Percy Shelley that seems always on the verge of breaking down the gate-posts of history and gusting into our world. The archival shackles in which the academic humanities prefer to keep their spectral versifiers and yawping hobgoblins enclosed seem especially frangible and ill-suited to the reluctant baronet’s “sword of lightning, ever unsheathed, which consumes the scabbard that would contain it.” Shelley is present in our efforts to meet and counteract the predicaments of our moment (from the mendacious mis-rule of government elites to the devastation of natural habitats for profit) in a way that Wordsworth, scrummily in awe of Nature and his own perception of it, is not – or at least, not so fluently.

Eleanor Marx Speaks!!! "Shelley's Socialism"

This is a Marxist evaluation of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley by Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling. It was delivered as a speech to the Shelley Society in April of 1888. This is the only complete and authoritative version of the speech that is available on line. It is almost impossible to find in a printed format.

The Peterloo Massacre and Percy Shelley by Paul Bond

Paul Bond’s essay is nothing less than a tour de force encapsulating and documenting Shelley’s reception by the radicals of his own era down to those of today. His article is wonderfully approachable, sparkles with erudition and introduces the reader to almost the entire radical dramatis personae of the 19th Century. I think it is vitally important for students of PBS to understand his radical legacy. And who better to hear this from than someone with impeccable socialist credentials: Paul Bond.

‘Your sincere admirer’: the Shelleys’ Letters as Indicators of Collaboration in 1821

The Shelleys’ collaborative literary relationship never had a constant dynamic: as with the nature of any human relationship, it changed over time. In Dr. Anna Mercer’s research she aims to identify the shifts in the way in which the Shelleys worked together, a crucial standpoint being that collaboration involves challenge and disagreement as well as encouragement and support. Dr. Mercer suggests despite speculation about an increasing emotional distance between Mary and Percy, the shift in collaboration is not so black-and-white as to reduce the Shelleys’ relationship to one simply of alienation in the later years of their marriage.

Paul Foot Speaks: The Revolutionary Percy Bysshe Shelley!!!

This is Paul Foot’s speech to the London Marxism Conference of 1981. His objective is to reconnect the left with Shelley. He does so in a surprising and original manner which is altogether convincing. Foot ably and competently traces the evolution of the modern left and demonstrates how it became disconnected from “the masses,” from real people with real-world concerns and issues. He longs for the “enthusiasm” that Shelley brought to the table. If ever there was a convincing “call to arms” that involves educating one’s self in the philosophy of a poet dead for 200 years, this is it.

“What Art and Poetry Can Teach Us about Food Security”: A TED Talk on John Keats and John Constable by Professor Richard Marggraf Turley.

Ginevra: A Shelley-Inspired Animation by Tess Martin and Max Rothman. By Jonathan Kerr

I recently had the opportunity to sit down and talk with two filmmakers who have contributed something truly remarkable to the Shelley revival. Tess Martin and Max Rothman have created Ginevra (2017), a short animated film that beautifully recreates one of Percy’s poems (also titled “Ginevra”) about the marriage and death of a young Italian woman. Created in cut-out animation with a voiceover narrator reciting lines from the original poem, Ginevra reimagines Shelley’s story, picking up where blanks appear in the unfinished manuscript. As it does so, it takes Shelley’s story in a bold, imaginative new direction.

Professor Michael Demson on the Real-World Impact of Shelley's Writing. A Summary by Jonathan Kerr.

Shelley’s poetry, Michael Demson argues, gave American workers a kind of writing that helped them to understand the political and economic forces to which they were subjected. “The Mask of Anarchy” was especially important in this context: written in easy-to-understand language, this poem attacks the power imbalances that helped to keep the powerful empowered and the poor disenfranchised. The conditions that made this sort of thing possible when Shelley lived—corrupt legal systems, unequal access to education, and working conditions that kept labourers underpaid and vulnerable—remained largely unchanged a century later in America. This is why, Demson alleges, a poem like “The Mask of Anarchy” could act as such a catalyzing force for New York’s industrial workers, not only providing common people with a language for understanding their problems, but also helping them to build a sense of community.

Frankenstein, a Stage Adaptation. Review by Anna Mercer

The last stage production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein I saw was a wonderful experience. The Royal Opera House’s ballet version of the novel was captivating and reflected the text’s themes of pursuit and terror with a striking intensity.[i] I’m always wary of adaptations of things I love, but after my positive experience at the ballet in London, I decided to go along to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein when I was visiting New York. This new production by Ensemble for the Romantic Century was held in the Pershing Square Signature Center, a lovely venue. But the play itself was a disappointment overall, with only a few redeeming features.

The Politics of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Shelley is a poet and thinker whose ideas have uncanny application to the modern era. His atheism, humanism, socialism, feminism, vegetarianism all resonate today. His critiques of the tyranny and religious oppression of the early 19th century seem eerily applicable to the early 21st century. He is the man who first conceived the concept of massive, non-violent protest as the most appropriate and effective response to authoritarian oppression. I have written about this in Shelley in our Time and What Should We Do to Resist Trump? But it may come as a surprise to many to learn Shelley also turned his mind to issues such as economics and the English national debt.

Today, the British government frames the argument around national debt by referring to the need for ‘us’ to make sacrifices or the fact that ‘we’ have been living beyond ‘our’ means and need austerity to survive economically. Despite evidence to the contrary, this ideology resonates with many people who think that in some way, we are all responsible for the financial crisis. We live within this widespread, false ideology, and some of us fight against it. However, a look back to the nineteenth century reveals that this fight was already taking place, and that capitalism was employing many of the tricks it still uses today. Jacqueline Mulhallen looks at the political life of the radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in her new biography and reveals that there was much more to him than first meets the eye.

Keats’s Ode To Autumn Warns About Mass Surveillance

John Keats’s ode To Autumn is one of the best-loved poems in the English language. Composed during a walk to St Giles’s Hill, Winchester, on September 19 1819, it depicts an apparently idyllic scene of harvest home, where drowsy, contented reapers “spare the next swath” beneath the “maturing sun”. The atmosphere of calm finality and mellow ease has comforted generations of readers, and To Autumn is often anthologised as a poem of acceptance of death. But, until now, we may have been missing one of its most pressing themes: surveillance.

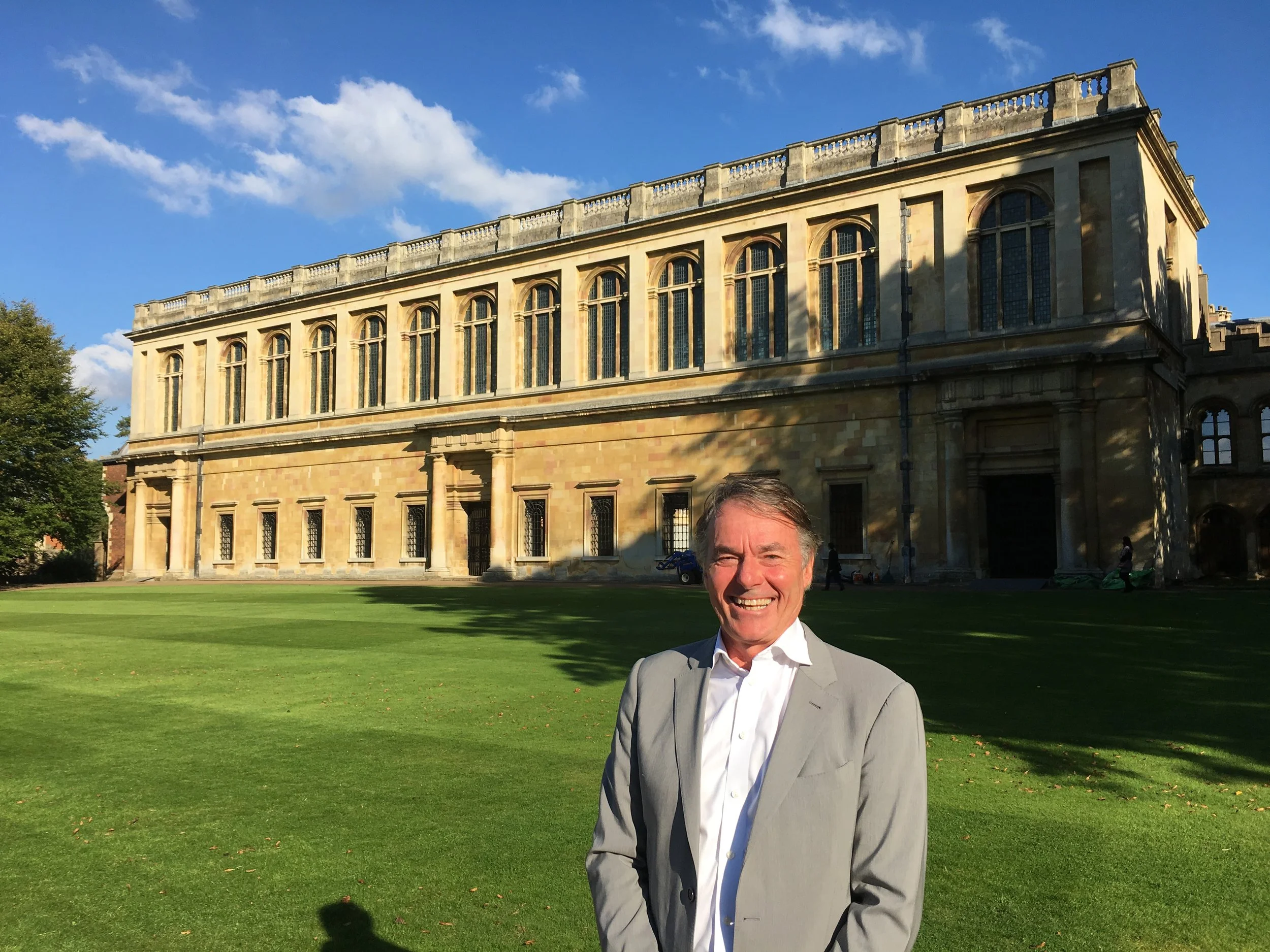

Why the Shelley Conference? By Anna Mercer

The Shelley Conference takes place in London at Institute for English Studies on the 15th and 16th of September. The keynote speakers are Prof. Nora Crook, Prof Kelvin Everest and Prof. Michael O’Neill. The conference is open to everyone - which is just how Shelley would have liked it. He would have also liked the fact that he and his wife are treated as co-equals and creative collaborators. I myself am honoured to be part of the conference and will be speaking on what I call "Romantic Resistance" - Shelley's strategies for opposing political and religious tyrannies. They are surprisingly applicable to our times! Here is co-organizer Anna Mercer on how this amazing conference came

Sir Humphrey Davy and the Romantics - an Online Course

Professor Sharon Ruston of Lancaster University is offering a free online course through Future Learn called "Humphry Davy: Laughing Gas, Literature, and the Lamp". These types of course are fun and informative. If you are interested in Shelley you will want to learn more about Davy because Shelley studied him closely. Shelley was one of the last great polymaths - he was well versed with a range of subjects that dwarfs most of his famous contemporaries. Science was one of them. To understand Shelley fully, you need to understand his interest in science - this course can help you to do this.

David, or The Modern Frankenstein: A Romantic Analysis of Alien: Covenant by Zac Fanni

I was very excited to hear that Shelley's poem Ozymandias features prominently in the new movie in the Alien franchise: Alien: Covenant. The poem's theme is woven carefully into the plot of the movie, with David (played again by Michael Fassbender) quoting the famous line, "Look on my works ye mighty and despair." What immediately drew me to Zac Fanni's excellent article was his discussion of the Ozymandias scene. However, what I found amounted to so much more. We are offered a kaleidoscopic array of classic romantic allusions including some which are more obvious, for example Frankenstein and Rime of the Ancient Mariner; and some that are decidedly less so: Shelley's Alastor makes an unexpected appearance!

Shelley Lives - Taking the Revolutionary Poet Shelley to the Streets.

Last fall Mark Summers did something absolutely fantastic: HE ACTUALLY TOOK SHELLEY'S POETRY TO A STREET PROTEST. Read his moving account of his experience. There are lessons for all of us in his experience. I think Mark's article is one of the most important I have published - and every student or teacher of Shelley needs to pay close attention to what Mark did. The revolutionary Shelley would be ecstatic!

Revolutionary Politics and the Poet. By Mark Summers

What I love about Mark Summers' writing is his ability to put Shelley in the context of his time, and then make what happened then feel relevant now. Both Mark and I sense the importance of recovering the past to making sense out of what is happening today. With madcap governments in England and the United States leading their respective countries toward the brink of authoritarianism, Shelley's revolutionary prescriptions are enjoying something of a renaissance; and so they should, we need Percy Bysshe Shelley right now!

In the Footsteps of Mary and Percy Shelley. By Anna Mercer

One of the great things about studying Shelley is where it can take you if you are intrepid. In the course of his short life he traveled to Ireland, Wales, Scotland, Devon, France, Switzerland and Italy - and some of the places he visited are among the most sublime and picturesque in Europe. Join Anna Mercer for a trip to Shelley's Mont Blanc!

The Political Fury of Percy Bysshe Shelley - by Mark Summers

The real Shelley was a political animal for whom politics were the dominating concern of his intellectual life. His political insights and prescriptions have resonance for our world as tyrants start to take center stage and theocracies dominate entire civilizations. Dismayingly, the problems we face are starkly and similar to those of his time, 200 years ago. For example: the concentration of wealth and power and the blurring of the lines between church and state. Some of you will have read my review of Michael Demson's history of Shelley's Mask of Anarchy. Guest contributor Mark Summers comment on the Mask says it all: "Disgustingly the only thing we need to update from Mask is the cast of villains, the substance is unchanged!." For Castlereagh read Rex Tillerson; for Eldon read Michael Flynn, for Sidmouth read Stephen Bannon and for Anarchy itself, we have, of course Trump:

Frankenstein at the fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva, review by Anna Mercer

The Frankenstein exhibition at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Geneva provides a journey, in which you first encounter the Shelleys’ works, and then the connections within those works to Geneva itself. We are presented with contemporary scenes of Geneva (in order to understand the Swiss town as Mary would have seen it), and the more unchanging forms of the French Alps.