Ginevra: A Shelley-Inspired Animation by Tess Martin and Max Rothman. By Jonathan Kerr

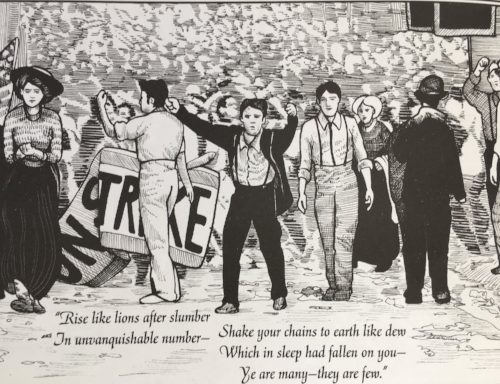

As Shelley enthusiasts, we are living through very exciting times. The bicentenaries marking the Shelleys’ legendary summer at Villa Diodati, the publication of Frankenstein, the Peterloo Massacre, and the composition of some of P.B.’s finest writing have brought with them a whole slew of Shelley commemorations. The 2017 Shelley Conference—the first of its kind since 1992—offered fascinating new perspectives for understanding the Shelleys and the issues that most dearly affected them. New graphic novels by Michael Demson and “Polyp” recreate some of the most pivotal events shaping Percy’s life and writing; feature-length films (here and here), a television production, and even a fashion show have found innovative ways to reimagine the Shelleys' life and times. Whether you’re a Shelley specialist, a costume-drama fanatic, a history buff, or a casual reader, the wave of interest in the Shelleys will certainly have something for you!

Michael Demson's graphic novel Masks of Anarchy (2013) tells the story of the Peterloo Massacre and Shelley's response to it.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down and talk with two filmmakers who have contributed something truly remarkable to the Shelley revival. Tess Martin and Max Rothman have created Ginevra (2017), a short animated film that beautifully recreates one of Percy’s poems (also titled “Ginevra”) about the marriage and death of a young Italian woman. Created in cut-out animation with a voiceover narrator reciting lines from the original poem, Ginevra reimagines Shelley’s story, picking up where blanks appear in the unfinished manuscript. As it does so, it takes Shelley’s story in a bold, imaginative new direction.

I want to get to what Tess and Max had to say about "Ginevra"—what attracted them to Shelley, and what made them want to recreate this little-known poem. First, however, I want to introduce you to Ginevra herself, and to the legend that has fascinated storytellers from the Renaissance to the present.

Over the centuries, the story of Ginevra has come together like an old wall, the kind you might see lining the streets of an ancient city. Early stories—our wall’s base—first emerge over the Renaissance as a Florentine legend about a woman named Ginevra degli Almieri. There were many stories of Ginevra circulating, but the most important one to Shelley, and the animation film it inspired, comes down to us from Marco Lastri's L'Osservatore Fiorentino, first published in 1776-78. In Lastri's telling, Ginevra is betrothed by her father to a nobleman named Francesco Agolanti. Ginevra lives unhappily with her husband for several years until, one day, relatives find her collapsed and unresponsive. Thinking that Ginevra has died, relatives arrange a funeral and lay the young woman to rest in a cathedral. Ginevra is not dead, however; after awakening in her tomb, Ginevra manages to escape the crypt and quickly heads for home. What follows is surprisingly comic by the standards of urban legends: thought to be a ghost by both her husband and father, Ginevra is refused entry to both households and left an exile on Florence’s streets. She eventually visits Antonio, her former lover, who promptly takes the destitute woman in. Ginevra’s husband, soon informed of the recent turn of events, angrily petitions a Florentine court for restitution; however, since Ginevra had been declared legally dead, the marriage had already been nullified. Ginevra, meanwhile, has been given “second life,” and is free to remarry. She and Antonio marry and, according to Lastri's story, live happily ever after.

"Ginevra degli Almieri," a Renaissance urban legend, tells of the burial and "afterlife" of a Florentine woman. (Caption: Antoine Wiertz, The Premature Burial, 1854.)

Mary and Percy read Lastri's strange tale, in addition to other Italian legends about premature entombment and "resurrection." A cursory glance through whatever Shelley volume may reside in your library will give you a sense of just how deep ran Shelley's appreciation for Dark Age tales of horror and the macabre!

As Shelley engages with this particular story, he transforms it in really interesting ways. Unlike Lastri's heroine, Shelley’s Ginevra is not a victim of superstition or medical malpractice; rather, she dies under mysterious circumstances. Shelley writes Ginevra's life and death in a deliberately ambiguous and open-ended fashion: is Ginevra murdered by her husband on account of her love affair with Antonio? Does Ginevra, dejected about her forced marriage, choose to end her life? However we choose to read Ginevra's story, it bears the mark of some of Shelley's most characteristic preoccupations as a writer: the need to confront the weight that age-old customs and their institutions place upon people's self-conception, worldview, and decisions; the challenges involved overcoming power structures and living a self-determined life; and the especially oppressive conditions that European societies placed upon the most vulnerable, like (in Ginevra's case) women and the young.

Whatever we choose to make of Ginevra's mysterious fate, the dirge recited at Ginevra's funeral hints at some sort of rebirth for the heroine. Like Lastri's version of the story, Shelley’s poem gestures to a second life for Ginevra, then, although what that might mean is left unclear. As Shelley cryptically writes,

"She is still, she is cold

On the bridal couch,

One step to the white deathbed,

And one to the bier,

And one to the charnel—and one, oh where?"

Ginevra (2017), the latest addition to our wall, weaves the Renaissance urban legend and the Romantic poem together. In a way, it “completes” Shelley’s poem by filling in scenes where the manuscript breaks off. But it also contributes something totally original to this centuries-old tale. Ginevra might strike you as both very historical and very current. I won’t give you many details about the short film, since I don't want to spoil it; you should watch it for yourself and form your own experience with this little gem. But I will give you a little bit of the discussions I’ve recently had with two people from the Ginevra team: Tess Martin, the director, and Max Rothman, the producer. Tess and Max opened up about what drew them to Shelley's little-known poem and why they were inspired to complete Ginevra's transition from a bit of Italian folklore, to a forgotten classic of British Romanticism, to a work of animated film.

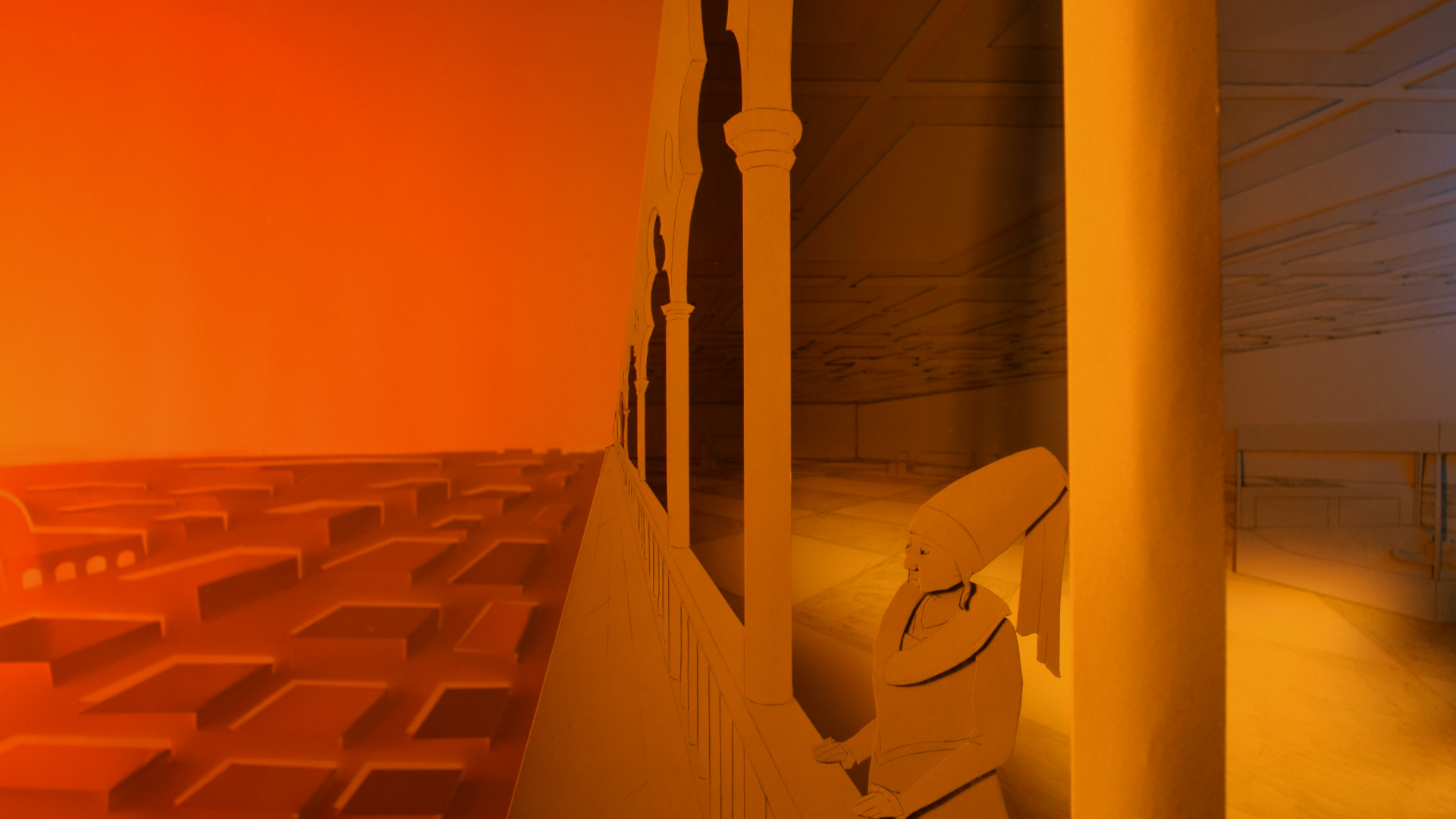

Ginevra came together with the spirit of collaboration in mind—fitting, given the story’s layered history. Shelley's poem first drew the interest of Max, a film producer who previously worked with NBC’s news department. He mentioned to me that the poem was perfect for the Campfire Poetry Project, a new initiative he’s working on that brings older poetry together with new art forms like animation, painting, and dance. The poem has a brooding atmosphere that Max recognized would lend itself nicely to visual illustration (the beautiful stills included below give you a nice idea of this); the unfinished poem also has a number of gaps that could free up an animator to take the story in interesting new directions.

A still from Ginevra.

Max brought the poem up with Tess, the director behind Ginevra. Shelley’s poem was one of 10 or 12 they discussed working on together. She, like Max, was attracted to the poem’s cliff-hanger ending. “It is interesting to think how Shelley would have finished his poem had he himself not died suddenly at sea,” she said. “In his poem, a bride dies on her wedding night. Would he have had her resurrect?”

More from Ginevra.

After doing some research into Shelley’s “Ginevra” and the Italian folk stories that inspired it, Tess set to work adding her own unique angle to the story. Ginevra’s fate is very different in all three versions, but all three also deal, in one way or another, with Ginevra’s rebirth into a new kind of life. I brought up with Tess how preoccupied Shelley was with forms of Old World tyranny, and particularly with the violence that marriage institutions permitted men to inflict against women and children—The Cenci, “Ginevra,” and Queen Mab all come to mind. Is this something that Tess wanted to explore as she depicted Ginevra’s death and rebirth? “Definitely there’s a feminist angle,” she told me, something that Tess also noticed in the Renaissance urban legend. In the original story, Ginevra finds a way to avoid her forced marriage, although “she still had to marry someone”; by contrast, something far more independent and strange awaits Tess’s Ginevra.

Max noted how interested he is in the overlap between the older kinds of stories told by poets and the newer techniques adopted by today’s filmmakers. “They’re working with the same storytelling archetypes we use now,” he says. In Ginevra’s case, the overlap is thematic as well. There’s something sadly current about Tess and Max’s animation, despite the old feel of Shelley’s language and the film’s Renaissance setting. All fairy-tales (and Ginevra certainly has a fairy-tale quality, despite its R-rating!) are timeless to one degree or another, since they are “about people trying to escape oppressors and be free,” Tess says.

Tess mentioned to me that for version of Ginevra's story, she wanted to evoke the tale's original Renaissance setting.

Tess had Blade Runner (1982) in mind when creating Ginevra.

When I asked Tess about whether she had any other films in mind when making Ginevra, she gave me an interesting one: Blade Runner. It surprised me initially, but it made more sense the more I thought about it. In Blade Runner, the more we look at the hyper-modern (or futuristic) problems encountered by the movie’s central figures, the more we realize that these problems—colonialism, gender inequality, the hubristic desire for too much knowledge or power—are in fact very old ones. It is just this interplay between history and the present that might have attracted Shelley to the first stories told about Ginevra degli Almieri. Shelley’s writing often captures the paradoxical sense that his period is both liberated from, and dominated by, history. This paradox also follows the story of Ginevra through the ages: a proto-feminist and victim of Old World violence, her story evokes both hope and fear about people's prospects for leading self-determined lives and creating change in the world.

How then would Shelley have finished his poem? Would Ginevra have emerged triumphant, liberated from her time and evolved into something "rich and strange" (to borrow lines from Shelley's epitaph)? Would Shelley have given us "Ginevra Unbound"? Or would the poem capture the possibility that history might be too strong for any one hero to combat on their own?

I, for one, am happy that these questions are left unresolved in Shelley's great, mysterious poem. From the gaps and fragments of Shelley's original have emerged new, exciting ways of engaging with his story. Tess and Max have returned to a classic Shelley poem, but they have also taken their heroine into bold and unpredictable territory. Looking back, in other words, has enabled them to imagine a new kind of future—for Ginevra, certainly, and perhaps for others as well. This, I think, would have made the Romantic rebel proud.

Jonathan Kerr is a university teacher and writer. He has recently completed his PhD from the University of Toronto with specialization in Shelley and other Romantics.

Tess Martin is an animator and film writer based in the Netherlands. She has received numerous grants, prizes and artist residencies in support of her work, which can be seen at festivals and in galleries worldwide. Learn more about Tess’ work here.

Max Rothman is a producer, editor, and filmmaker based in New York. He is the founder of Monticello Park Productions, a film production company that works with established and emerging auteurs from around the world. You can find more about Max’s work here.

Since its premiere in 2017, Ginevra has screened at a number of prominent film festivals and won several awards in film animation. Watch and learn more about Ginevra here.

"Ginevra," left incomplete on Shelley's death in 1822, was first published in Posthumous Poems (1824), a collection of Percy's poetry put together by Mary Shelley. You can read the poem in its entirety here.