Atheist, Lover of Humanity, Democrat

PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Jeremy Corbyn is Right: Poetry Can Change the World.

When Shelley said poets were the "unacknowledged legislators of the world", he used the term "legislator" in a special sense. Not as someone who "makes laws" but as someone who is a "representative" of the people. In this sense poets, or creators more generally, must be thought of as the voice of the people; as a critical foundation of our society and of our democracy. They offer insights into our world and provide potential solutions - they underpin our future. An attack on creators is therefore an attack on the very essence of humanity.

Fiona Sampson has written an absolutely brilliant article which I urge you to spend some time with and share widely. She opens by referencing Shelley's Defense of Poetry and his famous claim that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world." She also cites The Mask of Anarchy. You can find it here: Jeremy Corbyn is Right: Poetry Can Change the World.

In an other excellent article (From Glastonbury to the Arab Spring, Poetry can Mobilize Resistance) in the same online news source, Atef Alshaer, Lecturer in Arabic Studies at the University of Westminster, looks at other instances of poetry's power in the political context. "Poetry," he notes, "has remained a potent force for mobilization and solidarity." He traces the influence of Shelley to the words of the Tunisian poet, Abu al-Qassim al-Shabbi (1909-1934). He also observes that Shelley's words were "echoed across the Middle East within the context of what has been called the 'Arab Spring'."

It is important, however, to understand what Shelley meant when he said poets were the "unacknowledged legislators of the world." I believe it was PMS Dawson who pointed out that Shelley used the term "legislator" in a special sense. Not as someone who "makes laws" but as someone who is a "representative" of the people. In this sense poets, or creators more generally, must be thought of as the voice of the people; as a critical foundation of our society and of our democracy. They offer insights into our world and provide potential solutions - they underpin our future. An attack on creators is therefore an attack on the very essence of humanity.

Exposure to cultural works also engenders and inculcates empathy. Shelley thought poetry was the greatest expression of the imagination. This was important because as a skeptic he believed that the human imagination was the principle organ we use to understand the world. A defective imagination can lead to dangerous errors. You might, as did Coleridge, look at the sublimity of Mont Blanc and be misled into thinking it was the work of an external deity. And for Shelley, that is the beginning of a great error that would lead to the abdication of personal responsibility and accountability. He would prefer to look upon the sublimity of Mont Blanc and see a "vacancy". This doesn't mean he saw nothing. This simply means that there is nothing there except as we perceive it. In other words we make our own world. If we abdicate responsibility for what happens in the world, we get what we deserve.

I was recently at a ceremony hosted by the Government of Ontario that was intended to honour its most outstanding citizens. One of them was a "reverend" who was foolishly permitted to offer the "invocation." In the course of this she asked us to thank god for the fact that to the extent we had special gifts - we owed it to god. In other words, what "gifts" we have, we have because of god - they were given to us - not earned or developed. This pernicious idea is exactly the sort of nonsense Shelley was rebelling against. I almost turned my back on the podium.

It is therefore a most welcome development that as a result of the recent British election, poetry in general and Shelley in particular have been brought to center stage. Thank you Mr. Corbyn. And let us not underestimate the importance of Shelley to what happened. A general election in one the world's largest democracies was just fought out on ground staked out by Shelley 200 years ago. Labour's motto, "For The Many. Not For The Few", was directly taken from Shelley's "Mask of Anarchy. Read more about the history of this great poem here.

Watch Corbyn citing Shelley at Glastonbury here:

The motto brilliantly captured (or did it create?) an evolving zeitgeist. People are fed up with the current status quo: wealth is concentrating in fewer hands that at almost any point in human history. Shelley knew that. And he found an ingenious manner of expressing that thought. Someone in the Labour Party winged on to this and the rest is history. I firmly believe that motto was responsible for capturing the imagination of youth and bringing them to the polls. Was Shelley worth 30 seats? He may well have been.

But back to "unacknowledged legislators." I think we are better off to think of Shelley's statement as pertaining to all of the creative arts and not just poetry. Shelley was answering a particular charge at a particular juncture in history - his friend Peacock's suggestion that poetry was pointless. Today the liberal arts and the humanities are under a similar attack by the parasitic, cultural vandals of Silicon Valley. Right across the United States, Republican governors are rolling back support for state universities that offer liberal arts education. The mantra of our day is "Science. Technology. Engineering. Mathematics." Or STEM for short. This is not just a US phenomenon. I see it happening in Canada as well. There is a burgeoning sense that a liberal arts education is worthless.

Culture is worth fighting for - for the very reasons Shelley set out. What Shelley called a "cultivated imagination" can see the world differently - through a lens of love and empathy. Our "gifts" are not given to us by god - we earn them. They belong to us. We should be proud of them. The idea that we owe all of this to an external deity is vastly dis-empowering. And it suits the ruling order.

A corollary of this, also encapsulated in Shelley's philosophy, is the importance of skepticism. A skeptical, critical mind always attacks the truth claims of authority. And authority tends to rely upon truth claims that are disconnected from reality: America is great because god made it great. Thus Shelley was fond of saying, "religion is the hand maiden of tyranny."

It should therefore not surprise anyone that many authoritarian governments seek to reinforce the power of society's religious superstructure. This is exactly what Trump is doing by blurring the line between church and state. Religious beliefs dis-empower the people - they are taught to trust authority.

A recent development has been the re-emergence of stoicism - it is the pet ancient philosophy of the "tech bros", the overlords of Silicon Valley. And it is a very convenient one indeed - because it is in effect a slave's philosophy that teaches us to accept those things over which we have no control. And if the companion philosophy is that technological developments are inevitable, then stoicism suits the governing techno-utopian order perfectly. You can read what Cambridge philosopher Sandy Grant has to say about this here.

If there is an ancient philosophy that we need right now, it is skepticism - a philosophy which teaches to to question all authority. Coupled with an empathetic "cultivated imagination", developed through exposure to culture, you have a lethal one-two punch that threatens the foundation of all authoritarians.

We can thank Shelley for piecing this all together. Poets and creators may have been the "unacknowledged legislators of the world" in Shelley's time. But perhaps no longer. Now, let's haul ass to the barricades.

Pecksie and the Elf. What's in a Pet Name?

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, like almost everyone else on the planet, had pet names for one another. She was "Pecksie" and he was "Elf". PB's use of the name "pecksie" has actually attracted controversy. To find out why, I dug into the circumstances in which these names were used and the fascinating origin of "pecksie". Buckle up!

This is me with the Elf on my left and Pecksie on my right at the Bodmer Foundation in Geneva

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, like almost everyone else on the planet, had pet names for one another. She was "Pecksie" and he was "Elf". PB's use of the name "pecksie" has actually attracted controversy. To find out why, I dug into the circumstances in which these names were used and the fascinating origin of "pecksie". Buckle up!

Many years ago, while reading Anne Mellor's biography of Mary Shelley, I encountered her opinion of Percy’s use of a pet name for Mary. The name was “pecksie”. In Mellor’s opinion, this demonstrated “that he did not regard his wife altogether seriously as an author”. Cue my head exploding.

The pet name had appeared twice in the margins of a manuscript copy of Frankenstein that PB and MW had been jointly working on. Nora Crook, one of the foremost Shelley scholars alive today, supplies the details here:

“On the manuscript of Frankenstein are two comments by P. B. Shelley which have become infamous. Writing quickly, Mary Shelley had left off the first syllable of 'enigmatic' and ended up with 'igmmatic' (she was prone to double the letter 'm' while her husband had an ie/ei problem with words like 'viel' and 'thier'). Later she confused Roger Bacon with Francis Bacon. He scribbled 'o you pretty Pecksie' beside the first and 'no sweet Pecksie—twas friar Bacon the discoverer of gunpowder.'”

Most scholars, but not all, looked upon these pet names and comments as benign, even endearing. But remarks such as Mellor's were enough to fuel a controversy that persists to this day.

At this point I think we need to pause and give our heads a collective shake. Are we really having this conversation? Hopefully not. Nora Crook had, I think, a similar reaction and produced a brilliant, accessible, and sensitive essay on PB and MW's relationship, using the pet names as a jumping off point. She begins:

“Whether, however, a young woman who at nineteen could read Tacitus in the original would have felt intimidated by this may be doubted, especially one who called her spouse her 'Sweet Elf'. Between Pecksie and Elf, in terms of diminution, there is, prima facie, little to choose, any more than there is between the protagonists in the Valentine's Day newspaper advertisements where Snuggle Bum pledges love to Fluffkins. Intimate pet-names are almost invariably embarrassing to read. We do not know enough about the contexts in which these arose, whether they pleased or annoyed at the time, whether 'Pecksie' and 'Elf' were pleasant banterings or counters in underground hostilities. It would seem wise to suspend judgement and use them as evidence neither of an unproblematically equal relationship nor of one in which Mary Shelley was subordinated.”

I might also add here that the “young woman” in question was the daughter of no less a personage that Mary Wollstonecraft (the author of Vindication of the Rights of Women) and William Godwin (the author of Political Justice). Intellectually, she was a match for PB.

Even more interesting is the fact that, as Anna Mercer demonstrates, in the Shelley household, the term “pecksie” was applied by each partner to the other! For example, in a letter from 1815, Mary asked Percy to return one of her possessions, if he fails to do so, Mary tells him fondly, "I shall think it un-Pecksie of you".

This suggests that “pecksie” might have been more than just a pet name and rather a term that represented a constellated set of attributes. We might therefore be interested in what exactly it means to be “pecksie”; what behaviours or patterns of conduct fall into the category of “pecksian”? I think I am now in the position to shed some light on this!

So, let’s look at the origin of the term "pecksie". We begin again with Nora Crook suggests that it is "the name of the industrious bird in Mrs. Sherwood's The History of the Robins". Mary Martha Sherwood was an incredibly influential, best selling writer of children's literature in 18th and 19th century England. She was also an inveterate christian evangelist and proselytizer – which makes her books unlikely source material for the atheistical PB Shelley. But is Sherwood the source of the nickname? No.

In this, Crooks is unfortunately mistaken. The author of The History of Robins is not Sherwood, it was in fact Sarah Trimmer as Judith Barbour has pointed out.

And the correct spelling of the little robin’s name is in fact “Pecksy” and not "pecksie". Trimmer was in her own right an extremely famous children's author. Originally titled Fabulous Histories, Trimmers' book was continuously in print and a favourite of parents and children alike until after the First World War. After 1820, the book came to be known as The History of Robins or more simply, The Robins.

Born in 1741, Sarah Trimmer’s first book did not appear until 1780. Fabulous Histories, the book which established her reputation, was published in 1786. Today she is perhaps most famous for her periodical that systematically categorized and reviewed children’s literature: The Guardian of Education. The Hockcliffe Project is a remarkable cache of early children's literature which has recently been digitized. According to the uncredited author of the introductory essay on Sarah Trimmer:

“Trimmer's purpose in her Fabulous Histories was to teach children to behave with Christian benevolence towards all animals. Most of the book is spent inveighing against children and adults who torment animals, and also those who fall into the 'contrary fault of immoderate tenderness to them'. Both were common themes in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century children's (and adult's) literature. So too was the more overarching purpose of teaching the reader his or her place in the grand hierarchy of the universe. The reader learns that humans are at the head of creation, with power over all other living beings. Though this gives them the right to kill other animals and plants for food and to protect themselves, they may not without reason kill or hurt any creature without transgressing against the 'divine principle of UNIVERSAL BENEVOLENCE'.”

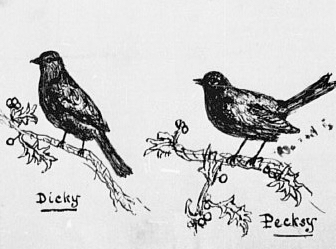

Trimmer aimed to teach these lessons by presenting the reader with two families, one of humans and one of robins. Both families, individually and through their interaction, are a microcosm of society. The reader is meant vicariously to learn the proprieties of family life and of behaviour to other parts of God's creation through the education by their respective parents of the two human children, Harriet and Frederick, and the four robin nestlings, Robin, Dicky, Flapsy and Pecksy. The human family, the Bensons, is fairly typical of the usual inhabitants of moral tales. They are affluent and landed. There is a largely absent father, and a loving if somewhat stern and pontificating mother. And there is one obedient and thoughtful child, Harriet, and another, younger sibling, more imprudent and thoughtless, but good at heart and responsive to a painstaking education. Though the family of robins was constructed on similar lines, with doting but stern parents and a brood which ranged from the docile and considerate Pecksy to the rash and conceited Robin, is was surely their presence which secured the book's lasting popularity.

Which brings us to the question of what it might mean in the Shelley household to be “pecksian”. I do not want to over play this hand, but if it is true that both PB and MW aspired to behave in a manner consistent with a set of "pecksian traits" and reproved one another when they failed to, it is worth while trying to understand what those traits were. It could tell us a surprising amount about the two of them.

Nora Crook would have us believe such behavior would be characterized as “industriousness”. However, having read a fair portion of Fabulous Histories, I think Pecksy’s personality is typified by a very different set of personality traits: she is obedient, amiable, self-effacing, considerate of others, self-sacrificing and a peacemaker.

The four nestlings from Fabulous Histories: Dicky, Pecksy, Flapsy, and Robin.

While the other three baby robins are continually in trouble, Pecksy distinguishes herself by her serene and sweet behavior. She is almost something of a “goody two shoes” who “wished to comply with every desire of her dear parents”. Perhaps not surprisingly, this makes Pecksy somewhat unpopular with her siblings, who grow quite jealous of her and are often reproved for this by their mother. For example:

“A few days after a fresh disturbance took place, all the little robins except Pecksy, in turn committed some fault or other for which they were occasionally punished; but she was of so amiable a disposition that it was her constant study to act with propriety, and avoid giving offence; on which account she was justly treated by her parents with distinguished kindness. This excited the envy of the others, and they joined together to treat her ill, giving her the title of the “pet”, saying that they made no doubt their father and mother would reserve the nicest morsels for their darling.”

Somewhat later we find this exchange between Pecksy and her mother after an incident which led to her being tormented by her siblings:

“‘I have been unhappy my dear mother’, said she, ‘but not so much as you suppose; and I am ready to believe that my dear brothers and sister were not in earnest in the severe things they said of me -- perhaps they only meant to try my affection. I now entreat them to believe, that I would willingly resign the greatest pleasure in life, could I by that means increase their happiness; and so far from wishing for the nicest morsel, I would content myself with the humblest fare rather than any of them should be disappointed.’ This tender speech had its desired effect it recalled those sentiments of love which envy and jealousy had for a time banished; all the nestlings acknowledged their faults, their mother forgave them and a perfect reconciliation took place to the great joy of Pecksy, and indeed of all parties”.

Later, Pecksy brings her mother a spider to eat. Her mother approvingly remarks, “How happy would families be if everyone like you, my dear, Pecksy consulted the welfare of the rest instead of turning their whole attention to their own interest”.

The day eventually arrives when the nestlings must learn how to fly. Several misadventures occur, notably to the headstrong Robin, but not to the observant Pecksy:

"Pecksy was fully prepared for her flight, for she had attentively observed the instruction given to the others and also their errors; she therefore kept the happy medium betwixt self-conceit and timidity indulging that moderated emulation which ought to possess every young heart; and resolving that neither her inferiors nor equals should soar above her she sprang from the ground and with a steadiness and agility wonderful for her first essay, followed her mother to the nest who instead of stopping to rest herself there flew to a neighbouring tree, that she might be at hand to assist Robin should he repent of his folly;…”

Readers familiar with the values both PB and MW came to cherish and extol in their poetry and prose will not be surprised, I think, to see in the character of the little robin called Pecsky an intimation of what was to come. That they themselves strove to behave in a “pecksian” manner and reproved one another when they failed (“I shall think it un-Pecksie of you.”) also tells us something about the value system operating in their home.

And can we go so far as to say PB's closing lines to Prometheus Unbound are pecksian?

To suffer woes which Hope thinks infinite;

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night;

To defy Power, which seems omnipotent;

To love, and bear; to hope till Hope creates

From its own wreck the thing it contemplates;

Neither to change, nor falter, nor repent;

This, like thy glory, Titan, is to be

Good, great and joyous, beautiful and free;

This is alone Life, Joy, Empire, and Victory.

Prometheus Unbound, Act IV, ll 570-578

Too far?? Okay....maybe a wee bit! But you smiled...I know you did.

And there is another value system at operation here: the humane treatment of animals. Trimmer's book was subtitled "The Instruction of Children Respecting Their Treatment of Animals". While Trimmer was no vegetarian (she approved of the killing of animals as long as it was done "not without reason") she nonetheless sought to inculcate in children a benevolence toward animals. Fabulous Histories is an excoriating morality tale in which those who torment animals are harshly punished. For me it is easy to trace a developmental arc for a sensitive child such as PB: from values such as these encountered in childhood, to the full blown vegetarianism of his adulthood.

To me, investigations like this are an eternal delight. We start with an uncharitable aspersion cast at our poet by a critic – all because he used a pet name for his lover. We are led to a delightful essay by a leading Shelley scholar and from thence first to the wrong book, but then to the right one. Along the way, we discover two largely forgotten giants of early children’s literature - Mary Sherwood and Sarah Trimmer. We finally arrive at a little robin – a nestling who embodied a set of character traits that came to be valued and extolled by two of the great writers of the 19th Century. Not a bad excursion. Tell me that wasn't fun!! All aboard for the next one?

Shelley Storms the Fashion World with Mask of Anarchy

In what is surely one of the most unusual but at the same time coolest uses of Shelley's poetry, English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton deployed Shelley's Mask of Anarchy in his recent runway show. The circumstances are quite extraordinary.

In what is surely one of the most unusual but at the same time coolest uses of Shelley's poetry, English fashion designer John Alexander Skelton deployed Shelley's Mask of Anarchy in his recent runway show. The circumstances are quite extraordinary.

First, Skelton's entire clothing line was inspired by, and I am not making this up, the Peterloo Massacre. According to Rebecca Gonsalves,

"Skelton was inspired by the Peterloo Massacre of 1918 [sic], which saw armed cavalry charge into a peaceful pro-democracy protest in Manchester, killing many and injuring hundreds, and in turn inspiring Shelley’s controversial poem."

While Gonsalves has the date of Peterloo wrong (it took place in 1819) she gets the rest absolutely right.

Skelton has to be one of the first clothing designers in history whose clothing line was inspired by a bloody massacre. This might strike many as unusual, but I think it is actually quite an important example of art interfacing with politics and political protest – in a manner Shelley would have whole-heartedly approved.

Skelton, hailing from York, had recently become aware of the events at Peterloo. According to Gonsalves, he was appalled not only by the loss of life and the carnage, but also the fact that two hundred years later, this massacre has not been properly memorialized by the English authorities. If anything it has been swept under the carpet.

From Michael Demson's Masks of Anarchy which you can buy here.

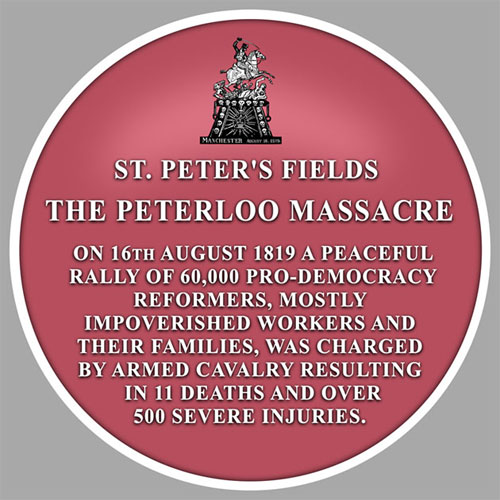

I have written at length about Peterloo in my review of Michael Demon’s graphic novel, “Masks of Anarchy”. It was also referred to by Mark Summers, in his article which I republished here. Briefly the facts are as follows: On the morning of 16 August 1818, a peaceful assembly of some sixty thousand English men, women and children began to gather in what is now St. Peter’s Square in Manchester (hence the name the massacre was popularly given: Peterloo). They did so quietly and with discipline. The protest was organized by the Manchester Patriotic Union and was to feature the famed orator Henry Hunt. Here is Demson's depiction of the event:

Hunt was to speak from a simple platform in front of what is now the Gmex Center. The crowd brought homemade banners that proclaimed REFORM, UNIVERSAL SUFFRAGE, EQUAL REPRESENTATION and LOVE. But before the speeches could begin, local magistrates ordered the local militia (known as ‘yeomanry”) to break up the meeting. This was done with extraordinary violence. As many as 12 protestors died and over 500 were wounded.

In the aftermath, journalists attempting to cover the massacre were arrested and news of the event suppressed. The businessman John Edwards Taylor was so shocked by what had happened that he went on to help set up the Guardian newspaper to ensure that the people would have a voice. Today the massacre still lacks an appropriate memorial despite decades of demand. For years, the event was commemorated only by a blue plaque which described the massacre as follows:

“The site of St Peters Fields where on 16th August 1819 Henry Hunt, radical orator addressed an assembly of about 60,000 people. Their subsequent dispersal by the military is remembered as “Peterloo”.

That the term “dispersal” is used to describe what was a massacre is an unconscionable euphemism. It was only in 2007 that the following plaque replaced it:

You can read about the Peterloo Memorial Campaign here.

According to Michael Scrivener, “the response of the radical leadership to Peterloo was surprisingly timid…the leaders must have been more alarmed than inspired by the revolutionary situation”. Hunt, for example, called for passive resistance in a variety of forms (such as tax resistance) and others sought a Parliamentary investigation. Only Richard Carlile (a radical journalist championed by Shelley and who later did much to keep Shelley’s reputation alive) proposed a meaningful response: he and a few others proposed a general strike – which never materialized. Shelley as we shall see went much further. Scrivener notes: "...the key to understanding the uniqueness of Shelley’s poem is his proposal for massive non-violent resistance.”

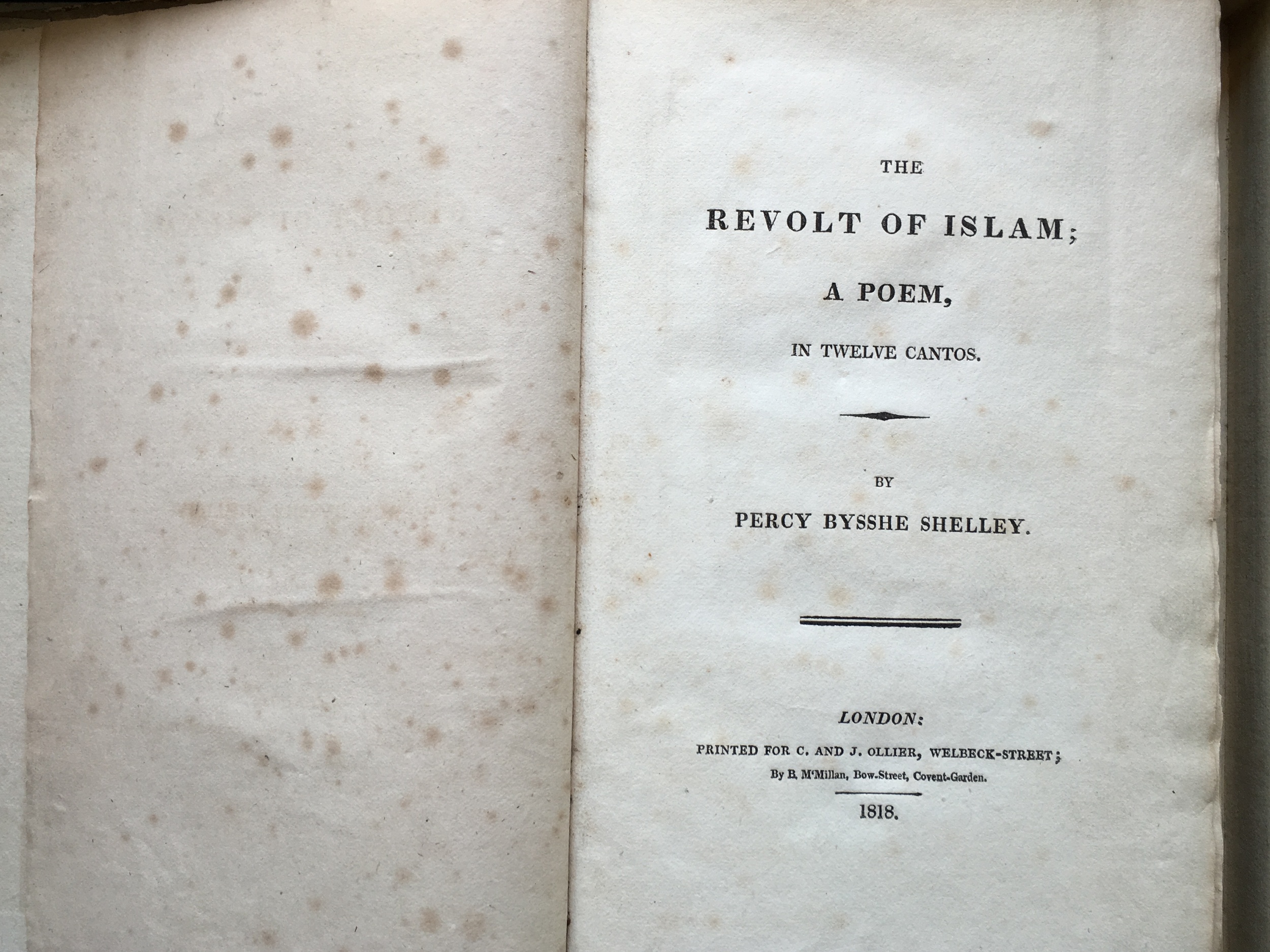

His proposal for non-violent resistance famously appeared in one of the single greatest political poems written in the English language, The Mask of Anarchy.

Skelton became aware of this and so he wove Shelley into the fabric, so to speak, of his fashion show as well. "I wanted to bring light to the blood that was spilled at Peterloo," said Skelton. He was frustrated that the massacre is so poorly remembered today despite its immense significance and resonance in our modern times.

Skelton was also aware that,

“after Peterloo, mass meetings were banned, so people showed their allegiances in discreet ways. The way they would show unity was with one singular thing that was incredibly powerful en masse. One of the most discreet was a ribbon between the first and second buttonhole of their fustian jacket.”

Fustian is a type of cotton cloth that was worn by workers during the 19th century. It was heavy and durable, and according to historian Paul Pickering radical elements of the English working class chose to wear fustian jackets as a symbol of their class allegiance. This was especially marked during the Chartist era. Pickering has called the wearing of fustian "a statement of class without words.” Readers of this blog will remember that Shelley was also a major influence on the Chartists.

This clearly resonated with Skelton who picked up this theme and presented a clothing line with strong historical echoes and overt political overtones. In her review of the show Gonsalves noted that

"Each model was dressed in roughly hewn garments that were snagged, sewn and patched as though they had been worn, and loved, forever. Checks and stripes were mixed and matched, and a limited colour palette focused on earthy brown, rust, cream and mushroom.[There was a] “sense of authentic imperfection to the waistcoats, collarless shirts, thick twills and too-short trousers. This was reinforced by Skelton’s use of street-cast older men who looked like they had lived lives in these clothes rather than simply donned them backstage.”

So where does Shelley come in? Well, it appears that the principle lens through which Skelton came to view the massacre was Shelley’s Mask of Anarchy. So powerfully did Shelley’s poem impress him that he had his models recite the entire 91 stanzas! If you follow this link you will arrive at Skelton’s Instagram account and can watch a rehearsal with one of the models reading from the Mask of Anarchy. It looks fantastic, thought regrettably the audio quality is poor.

All of this reminds us of the extraordinary longevity of Shelley's influence. The Mask of Anarchy was not even published in his lifetime, yet it continues to inspire and influence creators and politically active thinkers to this day. Well done Percy.

Shelley and Pope Francis

In the Mask of Anarchy, Shelley presents the tyrannical government of England as very clearly shown as being propped up by bishops and priests. Indeed, Shelley once characterized religion as the "hand maiden of tyranny". He said this because religion is faith-based and encourages people to discard their skepticism and accept things as they are. This is why the recent mania for "stoicism" is so popular in the alt-right movement. It is probably the LAST ancient philosophy we need to revive today. A point that has been eloquently made by Oxford philosopher Sandy Grant. As tyrants threaten to take the stage around the world, we need to keep a close eye on how religion is being used as a tool to control the people. This is why I think my article from last June on some then topical shenanigans of Pope Francis are apropos at this point in time. Enjoy.

In the Mask of Anarchy, Shelley presents the tyrannical government of England as very clearly shown as being propped up by bishops and priests. Indeed, Shelley once characterized religion as the "hand maiden of tyranny". He said this because religion is faith-based and encourages people to discard their skepticism and accept things as they are. This is why the recent mania for "stoicism" is so popular in the alt-right movement. It is probably the LAST ancient philosophy we need to revive today; a point that has been eloquently made by Oxford philosopher Sandy Grant. As tyrants threaten to take the stage around the world, we need to keep a close eye on how religion is being used as a tool to control the people. We are faced by a new administration in Washington well stocked with evangelical Christians, many of whom are hard-line "dominionists"; Stephen Bannon, Kellyanne Conway and Betsy de Vos are examples. Christian dominionism is a radical ideology whose adherents believe that it is their duty to seize control of the civic institutions and rule the United States as a theocratic Christian state. Dominionists oppose and seek the repeal of the 1st Amendment which enshrined the separation of church and state.

Which brings us to Jorge Gergoglio, otherwise known as Pope Francis.

Gergoglio is probably a very good man, but as pope, he is very fond of highly symbolic gestures that change very little: for example, on the question of gays priests in the church, he has done absolutely nothing except express the sort of benign sympathy that garners headlines. Here is how a sympathetic, beguiled reporter for the New Yorker reacted:

Who am I to judge?” With those five words, spoken in late July [2013] in reply to a reporter’s question about the status of gay priests in the Church, Pope Francis stepped away from the disapproving tone, the explicit moralizing typical of Popes and bishops. This gesture of openness, which startled the Catholic world, would prove not to be an isolated event.

And indeed, the writer was correct. He did step away from disapproving tones, it eas not isolated; but he has done little more. Another example is his non-action on the issue of women priests. Gergoglio has repeatedly stated that women can not and will not be ordained. More recently, we have his attack on the materialism of christmas. Popular to be sure, but what about the materialism of the catholic church itself? Well, he has said nothing.

Gergoglio the news last summer for more non-action on the paedophile priests and their enablers in the Catholic church. The Guardian reported that

"Catholic bishops who fail to sack paedophile priests can [now] be removed from office under new church laws announced by Pope Francis.".

There are more than a few problems with this. The first question has to be, "You are kidding me, they didn't have a rule about this already?" Are we supposed to congratulate the Vatican on introducing a rule that should have been introduced decades ago - or the fact that there even needed to BE a rule? But then critics of the pope pointed out that yes, there already IS a rule. According to the Guardian,

"While acknowledging that church laws already allowed for a bishop to be removed for negligence, Francis said he wanted the “grave reasons” more precisely defined. However, doubts remain about the Vatican’s commitment to tackling the issue."

So what exactly has Gergoglio done? Well, almost nothing it would seem. This attention-grabbing move seems to be window dressing designed to distract attention from actions he has taken recently to actually protect priests accused of covering up abuse. The Guardian:

The move comes shortly after the pontiff moved to defend a French cardinal accused of covering up abuse. Philippe Barbarin, the archbishop of Lyon, is facing criticism for his handling of allegations made against Bernard Preynat, a priest in the diocese who has been charged with sexually abusing boys.

Gergoglio also seems to be moving to maintain in office his financial chief, Cardinal George Pell - a man accused of covering up systemic child abuse in Australia. As the Guardian reports, Pell has improbably denied all knowledge of priests abusing children as he rose through the ranks of the Catholic church. As recently as November last year Pell was still refusing the answer questions about the issue and he is still a cardinal.

Which brings us to Shelley.

Over a year ago, a fellow student in Professor Eric Alan Weinstein’s Open Learning course, “The Great Poems: Unbinding Prometheus” posed the following question to the community.

“I'm wondering what Shelley would've made of the Pope's visit to America (something that was up close and personal for those of you in Philly). I was jazzed by his remarks about climate change, the war economy, social justice and the widening economic divide in this country. Then, boom, I read that he met in secret with Kentucky County Clerk Kim Davis (the elected official who refused to give marriage licenses to gay couples). So I guess the Pope's great compassion for prisoners, refugees, the poor and minorities of all stripes does not extend to gay couples. So much of what he said in public was worthwhile, but what he did in private was revealing and makes me think this holy man has a keen and secular focus on his public image. Interesting to see what was selected for presentation on the outside (I'm not challenging the sincerity of that) and what was kept behind the "veil" that Shelley tells us must be rent.”

I thought this was an excellent question and one that remains worth considering at length.

Shelley was profoundly anti-clerical and an avowed atheist fond of referring to religion in terms such as: “the hand-maiden of tyranny”. He certainly had no truck with the priests of his day, so what might he had thought about the pope’s visit to America -- particularly in light of the pope's latest propagandistic actions? Given the fawning reaction accorded to Gergoglio by American political leaders and even an otherwise skeptical media, my opinion is that Shelley would have been appalled.

Readers approaching Shelley for the first time are often genuinely confused by what they find. In my article "Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat." What did Shelley Mean? I have offered a partial explanation - one which I will elucidate in much greater detail in the future. Most modern readers are genuinely surprised to learn he was a skeptic and an atheist. The reasons for this are complex, but for the purposes of this article, suffice to say that thanks to centuries of sometimes deliberate mis-readings, modern readers expect a somewhat florid, vapid lyrical poet who wore puffy shirts. But what they find is radically different: they find an intensely political writer for whom, according to Timothy Webb, “politics were probably the dominating concern in [his] intellectual life."

The signs can be confusing in other ways because Shelley often used overtly religious language for decidedly atheistical, secular purposes. Missing the irony in his use of religious terminology, many otherwise astute readers have concluded that he was a closet Christian.

But he was not. Shelley was an atheist; he was a skeptic; and he was a philosophical anarchist. He viewed religion as perhaps the most pernicious force in society. As an anarchist and a skeptic he saw religion and its adherence to dogma and tradition as the number one enemy of political reform. As an anarchist and a skeptic he was an opponent of most forms of state government and all forms of religious tradition and dogma. He would have viewed the Catholic church as one of the most corrupt institutions on earth - and one of the most dangerous. He would have been appalled to see the coverage of the pope's visit to America, for reasons I will try to elucidate.

I had exactly the same reaction to the secret meeting pope Francis had with the county clerk as my fellow student did. There is no disguising hypocrisy that is this bold and this brazen. It is fitting that what Gergoglio conceived of as, and desired to be, a secret meeting was nothing of the sort as he was almost immediately betrayed by the clerk's lust for publicity and acknowledgement. It was her own lawyer that leaked the fact the meeting took place - he revealed they planned all along to make the photographs public. I am sure pope Francis would have been very happy to have that secret meeting remain a secret - which also begs the question of exactly how many other secret meeting there were or have been over time.

But back to Shelley. Why would he have been so concerned? Perhaps because Gergoglio's messages were so smoothly, so seductively and so beautifully adapted to the troika of modern woes my fellow student so aptly identified: the environment, the seemingly endless wars we are fighting and the growing divide between rich and poor. The Vatican has achieved enormous mileage from utterly empty gestures such as Gergoglio’s decision not to wear the expensive red shoes favoured by his predecessors.

Pope Benedict wearing red Prada shoes.

The announcement that he now has "rules" to deal with bishops who hide paedophile priests falls into the same category.

I believe that the Gergoglio's messages regarding climate change, war, and poverty are important, but they are also dangerous because they operate to distract us from his failure to address the systemic problems associated with the catholic church. Chief among these is the fact that it is founded on allegedly "sacred texts" that are, as Tim Whitmarsh noted, imagined to be “nonnegotiable contracts with the divine, inspired or authored as they are by god himself.” (Whitmarsh, 28). The Greeks, to whom Shelley looked as a primary source for his philosophical foundation, had no such concept of books that possessed magical properties and which contained the source of ultimate truth. Such beliefs are unique to the world’s monotheistic religions. The pope has been accorded a similarly magical status by the church: edicts promulgated by a pope are believed to be infallible – they can not be questioned or altered – ever.

Late in life my father, a converted roman catholic, lost his faith. The reason for this was the failure of the church to address the systemic sexual abuse of children by priests - and the centuries long cover up. By addressing issues such as climate change and the evils of capitalism, the pope is distracting us from the real problems that are rotting the church. The Vatican is a walled nation state. A critic of the evils of capitalism, Gergoglio sits astride an entity that is awash in obscene amounts of money -- all of it gained through the very capitalist system the pope so disingenuously attacks. The Catholic church owns some of the most valuable property on the planet.

This pope needs to put his own house in order before he comes to the rest of us with homilies on what ails the world. Gergoglio should act to ordain women, cast out his own capitalistic devils, and don sack cloth in order to crisscross the globe begging forgiveness for what the church did to indigenous cultures around the world. The Vatican should institute a truth and reconciliation commission. Gergoglio should renounce his papal “infallibility." The church should pay reparations. Why is it only secular governments that are apologizing to indigenous peoples and paying reparations? As for the sexual abuse scandals? Why is this still an issue? The church has the names. The church knows exactly who did what and to whom. They have files that must fill warehouses. Turn everything over to the police. There is no role for the church in investigating the egregious crimes committed againstchildren. None. The police have experts who deal daily in sexual abuse matters. The pope has the power to turn over everything to the police. He should do it NOW!

Shelley would be dismayed to think that after the passage of 200 years, people in vast numbers yet approach the subject of religion credulously. Many of them still actually believe that a ghost impregnated a virgin.

A poem of Shelley's that I would recommend to those who care to go deeper would be "Peter Bell the Third". This is an unjustly overlooked poem. Is it EVER taught at university? I doubt it. P.M.S. Dawson argues that the subject of this poem is the alienation of society from itself (Dawson, 199). Dawson writes, "The key to this alienation is in Shelley's view the acceptance of religious fictions....Shelley identifies the slavish acceptance of a corrupt religion with devotion to tyrannical social order." (Dawson, 199). Shelley himself pointed to religion as the "prototype of human misrule." Dawson: "God, the Devil and Damnation may be absurd fictions, but men's belief in them has also made them sinister and palpable realities." (Dawson, 200) As Shelley perceptively notes, "'Tis a lie to say God damns." Why? Because we damn ourselves.

Shelley very clearly saw men like Gergoglio as part of the "ghastly masquerade" of the Mask of Anarchy. He even has a line which seemed to anticipate him:

"Next came Fraud, and he had on,

Like Eldon, an ermined gown;

Clothed with the Bible, as with light,

And the shadows of the night,"

Mask of Anarchy (ll 14-15, 22-23)

Works Cited

Dawson, P.M.S. The Unacknowledged Legislator: Shelley and Politics. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980. Print.

Witmarsh, Timothy, Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World. Knopf, 2015. Print

"I am a Lover of Humanity, a Democrat and an Atheist.” What did Shelley Mean?

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.Five explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

Part of a new feature at www.grahamhenderson.ca is my "Throwback Thursdays". Going back to articles from the past that were favourites or perhaps overlooked. This was my first article for this site and it was published at a time when the Shelley Nation was in its infancy. I have noted how few folks have had a chance to have a look at it. And so I am taking this opportunity to take it out for another spin. If you have seen it, why not share it, if you have not seen it, I hope you enjoy it!

The "catch phrase" I have used for the Shelley section of my blog ("Atheist. Lover of Humanity. Democrat.") may require some explanation. The words originated with Shelley himself, but when did he write it, where did he write it and most important why did he write it. Many people have sought to diminish the importance of these words and the circumstances under which they were written. Some modern scholars have even ridiculed him. I think his choice of words was very deliberate and central to how he defined himself and how wanted the world to think of him. They may well have been the words he was most famous (or infamous) for in his lifetime.

Shelley’s atheism and his political philosophy were at the heart of his poetry and his revolutionary agenda (yes, he had one). Our understanding of Shelley is impoverished to the extent we ignore or diminish its importance.

Shelley visited the Chamonix Valley at the base of Mont Blanc in July of 1816.

"The Priory" Gabriel Charton, Chamonix, 1821

Mont Blanc was a routine stop on the so-called “Grand Tour.” In fact, so many people visited it, that you will find Shelley in his letters bemoaning the fact that the area was "overrun by tourists." With the Napoleonic wars only just at an end, English tourists were again flooding the continent. While in Chamonix, many would have stayed at the famous Hotel de Villes de Londres, as did Shelley. As today, the lodges and guest houses of those days maintained a “visitor’s register”; unlike today those registers would have contained the names of a virtual who’s who of upper class society. Ryan Air was not flying English punters in for day visits. What you wrote in such a register was guaranteed to be read by literate, well connected aristocrats - even if you penned your entry in Greek – as Shelley did.

The words Shelley wrote in the register of the Hotel de Villes de Londres (under the heading "Occupation") were (as translated by PMS Dawson): “philanthropist, an utter democrat, and an atheist”. The words were, as I say, written in Greek. The Greek word he used for philanthropist was "philanthropos tropos." The origin of the word and its connection to Shelley is very interesting. Its first use appears in Aeschylus’ “Prometheus Bound” the Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound. Aeschylus used his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered philanthropy to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”.

What do the words Shelley chose mean and why is it important? First of all, most people today would shrug at his self-description. Today, most people share democratic values and they live in a secular society where even in America as many as one in five people are unaffiliated with a religion; so claiming to be an atheist is not exactly controversial today. As for philanthropy, well, who doesn’t give money to charity, and in our modern society, the word philanthropy has been reduced to this connotation. I suppose many people would assume that things might have been a bit different in Shelley’s time – but how controversial could it be to describe yourself in such a manner? Context, it turns out, is everything. In his time, Shelley’s chosen labels shocked and scandalized society and I believe they were designed to do just that. Because in 1816, the words "philanthropist, democrat and atheist" were fighting words.

Shelley would have understood the potential audience for his words, and it is therefore impossible not to conclude that Shelley was being deliberately provocative. In the words of P.M.S. Dawson, he was “nailing his colours to the mast-head”. As we shall see, he even had a particular target in mind: none other than Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Word of the note spread quickly throughout England. It was not the only visitor’s book in which Shelley made such an entry. It was made in at least two or three other places. His friend Byron, following behind him on his travels, was so concerned about the potential harm this statement might do, that he actually made efforts to scribble out Shelley’s name in one of the registers.

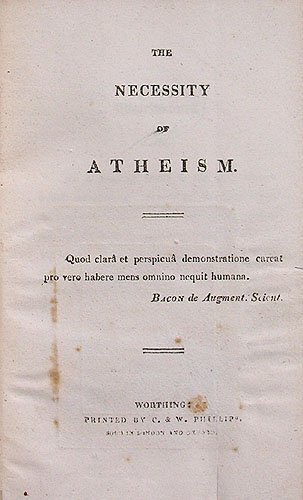

While Shelley was not a household name in England, he was the son of an aristocrat whose patron was one of the leading Whigs of his generation, Lord Norfolk. Behaviour such as this was bound to and did attract attention. Many would also have remembered that Shelley had been actually expelled from Oxford for publishing a notoriously atheistical tract, The Necessity of Atheism.

Shelley's pamphlet, "The Necessity of Atheism"

While his claim to be an atheist attracted most of the attention, the other two terms were freighted as well. Democrat then had the connotations it does today but such connotations in his day were clearly inflammatory (the word “utter” acting as an exclamation mark). The term philanthropist is more interesting because at that time it did not merely connote donating money, it had overt political and even revolutionary overtones. To be an atheist or a philanthropist or a democrat, and Shelley was all three, was to be fundamentally opposed to the ruling order and Shelley wanted the world to know it.

What made Shelley’s atheism even more likely to occasion outrage was the fact that English tourists went to Mont Blanc specifically to have a religious experience occasioned by their experience of the “sublime.” Indeed, Timothy Webb speculates that at least one of Shelley’s entries might have been in response to another comment in the register which read, “Such scenes as these inspires, then, more forcibly, the love of God”. If not in answer to this, then most certainly Shelley was responding to Coleridge, who, in his head note to “Hymn Before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni,” had famously asked, “Who would be, who could be an Atheist in this valley of wonders?" In a nutshell Shelley's answers was: "I could!!!"

Mont Blanc, 16 May 2016, Graham Henderson

The reaction to Shelley’s entry was predictably furious and focused almost exclusively on Shelley’s choice of the word “atheist”. For example, this anonymous comment appeared in the London Chronicle:

Mr. Shelley is understood to be the person who, after gazing on Mont Blanc, registered himself in the album as Percy Bysshe Shelley, Atheist; which gross and cheap bravado he, with the natural tact of the new school, took for a display of philosophic courage; and his obscure muse has been since constantly spreading all her foulness of those doctrines which a decent infidel would treat with respect and in which the wise and honourable have in all ages found the perfection of wisdom and virtue.

Shelley’s decision to write the inscription in Greek was even more provocative because as Webb points out, Greek was associated with “the language of intellectual liberty, the language of those courageous philosophers who had defied political and religious tyranny in their allegiance to the truth."

The concept of the “sublime” was one of the dominant (and popular) subjects of the early 19th Century. It was widely believed that the natural sublime could provoke a religious experience and confirmation of the existence of the deity. This was a problem for Shelley because he believed that religion was the principle prop for the ruling (tyrannical) political order. As Cian Duffy in Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime has suggested, Prometheus Unbound, like much of his other work, “was concerned to revise the standard, pious or theistic configuration of that discourse [on the natural sublime] along secular and politically progressive lines...." Shelley believed that the key to this lay in the cultivation of the imagination. An individual possessed of an “uncultivated” imagination, would contemplate the natural sublime in a situation such as Chamonix Valley, would see god at work, and this would then lead inevitably to the "falsehoods of religious systems." In Queen Mab, Shelley called this the "deifying" response and believed it was an error that resulted from the failure to 'rightly' feel the 'mystery' of natural 'grandeur':

"The plurality of worlds, the indefinite immensity of the universe is a most awful subject of contemplation. He who rightly feels its mystery and grandeur is in no danger of seductions from the falsehoods of religious systems or of deifying the principle of the universe” (Queen Mab. Notes, Poetical Works of Shelley, 801).

He believed that a cultivated imagination would not make this error.

This view was not new to Shelley, it was shared, for example, by Archibald Alison whose 1790 Essays on the Nature and Principles of Taste made the point that people tended to "lose themselves" in the presence of the sublime. He concluded, "this involuntary and unreflective activity of the imagination leads intentionally and unavoidably to an intuition of God's presence in Creation". Shelley believed this himself and theorized explicitly that it was the uncultivated imagination that enacted what he called this "vulgar mistake." This theory comes to full fruition in Act III of Prometheus Unbound where, as Duffy notes,

“…their [Demogorgon and Asia] encounter restates the foundational premise of Shelley’s engagement with the discourse on the natural sublime: the idea that natural grandeur, correctly interpreted by the ‘cultivated imagination, can teach the mind politically potent truths, truths that expose the artificiality of the current social order and provide the blueprint for a ‘prosperous’, philanthropic reform of ‘political institutions’.

Shelley’s atheism was thus connected to his theory of the imagination and we can now understand why his “rewriting” of the natural sublime was so important to him.

If Shelley was simply a non-believer, this would be bad enough, but as he stated in the visitor’s register he was also a “democrat;” and by democrat Shelley really meant republican and modern analysts have now actually placed him within the radical tradition of philosophical anarchism. Shelley made part of this explicit when he wrote to Elizabeth Hitchener stating,

“It is this empire of terror which is established by Religion, Monarchy is its prototype, Aristocracy may be regarded as symbolizing its very essence. They are mixed – one can now scarce be distinguished from the other” (Letters of Shelley, 126).

This point is made again in Queen Mab where Shelley asserts that the anthropomorphic god of Christianity is the “the prototype of human misrule” (Queen Mab, Canto VI, l.105, Poetical Works of Shelley, 785) and the spiritual image of monarchical despotism. In his book Romantic Atheism, Martin Priestman points out that the corrupt emperor in Laon and Cythna is consistently enabled by equally corrupt priests. As Paul Foot avers in Red Shelley, "Established religions, Shelley noted, had always been a friend to tyranny”. Dawson for his part suggests, “The only thing worse than being a republican was being an atheist, and Shelley was that too; indeed, his atheism was intimately connected with his political revolt”.

Three explosive little words that harbour a universe of meaning and significance.

1816: The Message of Diodati

Percy and Mary Shelley joined Byron in Geneva for part of the summer of 1816. They spent much of their time at Byron's residence: the Villa Diodati. It was there that some of the most important ideas of the Romantic era were conceived. Can we distill one of the core principles? I think we can. Join me for the first installment of my exploration the life and times of the extraordinary Percy Bysshe Shelley. Episode One - 1816: The Message Of Diodati

Percy and Mary Shelley joined Byron in Geneva for part of the summer of 1816. They spent much of their time at Byron's residence: the Villa Diodati. It was there that some of the most important ideas of the Romantic era were conceived. Can we distill one of the core principles? I think we can. Join me for the first installment of my exploration the life and times of the extraordinary Percy Bysshe Shelley. Episode One - 1816: The Message Of Diodati

Note to viewers. This episode of The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley is a "pilot". It may be a little rough around the edges, but based on what I learned from its production, I can guarantee better production values going forward. Please subscribe to my channel and leave me your comments. If you have an idea for an episode, I would love to hear it. Thank you and enjoy!

Percy Bysshe Shelley In Our Time.

MASSIVE, NON-VIOLENT PROTEST. FROM SHELLEY TO #WOMENSMARCH

Shelley imagines a radical reordering of our world. It starts with us. Are we up for the challenge? Shelley was. Take the closing words of Prometheus Unbound and print them out. Pin them to your fridge, memorize them, share them with loved ones and enemies alike. Let them inspire you. Let them change you. And never forget he was 27 when he wrote these words and dead with in three years.

Shelley, who among poets was one of the most supremely political animals, described the condition of England in 1819 in a manner which should make us fear for our future. Around the globe tyrants and demagogues are taking power or going mainstream and entire civilizations are subject to theocratic dictatorships. If we don't want our future to look like this, we will need to organize and resist:

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,—mud from a muddy spring;

Rulers who neither see nor feel nor know,

But leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

A people starved and stabbed in th' untilled field;

An army, whom liberticide and prey

Makes as a two-edged sword to all who wield;

Golden and sanguine laws which tempt and slay;

Religion Christless, Godless—a book sealed;

A senate, Time’s worst statute, unrepealed—

Are graves from which a glorious Phantom may

Burst, to illumine our tempestuous day.

England 1819, Percy Bysshe Shelley

Jonathan Freedland, writing in the Guardian, has some surprisingly Shelleyan proposals and suggestions to avoid this potential future. The Guardian's coverage has in general been superb. This can be contrasted with some of the coverage of Trump's inauguration address in the New York Times. One article (see insert) referred to Trump’s demagogic, xenophobic anti-intellectual inaugural diatribe as “forceful.” This is a disgraceful, shameful euphemism.

Freedland, and the Guardian, on the other hand have called a spade a spade.

What fascinated me about Freedland’s article was the language he used. It struck me as distinctly reminiscent of Shelley – particularly in the many passages that focus on resistance and nonviolent protest. It was redolent of the Mask of Anarchy:

"So what should those who have long dreaded this moment do now? For some, the inauguration marks the launch of what they’re already calling “the resistance”, as if they are facing not just an unloved government but a tyranny. Note the banner held aloft by one group of demonstrators that read simply: “Fascist.”

"Placards and protests will have their place in the next four years. But those who want to stand in Trump’s way will need to do more than simply shake their fists. The work of opposition starts now."

And if people don’t think that what we are facing is a potential tyranny, we need look no further than the fact that Trump began signing executive orders immediately – the first one designed to role back the Affordable Care Act. Neither arm of the government has even had the opportunity to consider how to do this or with what what it should be replaced. In addition, he has ordered the creation of a missile defense system aimed squarely at southeast Asia, and created a new national holiday to celebrate “patriotism” – a euphemism no doubt for his own for Trumpian brand of xenophobic jingoism. Are you worried yet? This is day ONE.

Freedland goes on to set out what he sees are the principal ways opposition to Trump can be organized:

“At the front of the queue, as it were, are the press. There’s no doubt Trump sees it that way. With Clinton out of the way, the media has become his enemy of choice. The media’s very existence seems to infuriate him. Perhaps because it’s now the only centre of power he doesn’t control. With the White House and Congress in Republican hands, and the casting vote on the supreme court an appointment that’s his to make, it’s no wonder the fourth estate rankles: he already controls the other three.

That puts a great burden of responsibility on the press. Trump has majorities in the House and Senate, so often it will fall to reporters to ask the tough questions and hold the president to account. And it won’t be easy, if only because war against Trump is necessarily a war on many fronts. Just keeping up with his egregious conflicts of interests could be a full-time job, to say nothing of his bizarre appointments, filling key jobs with those who are either unqualified or actively hostile to the mission of the departments they now head. It’s a genuine question whether the media has sufficient bandwidth to cope.”

I agree on all counts. And we would do well to ruminate on one of the many reasons we are in this mess in the first place. We are here because Silicon Valley’s right wing brand of cyberlibertarianism has attacked some of the very foundations of our democracy and marginalized the left. The media has been hamstrung. And while we still have vibrant top-line outlets such as the Guardian and the NYTimes, local news has virtually ceased to exist. And social media has simply NOT replaced this – a point Freedland also makes. I think we need to usher in an era of mass civil disobedience and protest and that includes fighting back at corporations like Google who seek to dominate the way we see the world. My message to Millennials would be to remind them that, no, you do not simply have to accept things the way they are and slavishly follow brands. Once upon a time it was cool to say “fuck you” to corporations and “the man.” Here is Freedland:

“But that will count for nothing if there is not a popular movement of dissent, one that exists in the real world beyond social media. Some believe the mass rally is about to matter more than ever. Trump, remember, is a man who gets his knowledge of the world from television, and who is obsessed by ratings. How better to convey to him the public mood of disapproval than by forcing him to see huge crowds on TV, comprised of people who reject him?

And this will have to be backed by serious, organized activism. The left can learn from the success of the Tea Party movement, which did so much to obstruct Barack Obama. That will force congressional Democrats to consider whether they too should learn from their Republican counterparts, thwarting Trump rather than enabling him."

The title of Freedland’s article is this:

"Divisive, ungracious, unrepentant: this was Trump unbound"

Peter Paul Reubens, Prometheus Unbound. 1611-12.

I am fascinated by this because it seems to be a possibly ironical reference to Shelley's great poem, Prometheus Unbound whose villain, Jupiter shares many characteristics with Trump. In Shelley’s poem, however, it is the hero, Prometheus, who is unbound and overthrows Jupiter. Here it is the forces of darkness that have been unbound. Prometheus Unbound is a mythic drama, so we should not look to it for the sort of political commentary we saw in his short poem England 1819, quoted above. But it does have some startling imagery which describes the sort of world we could live into if we stand by and let fascists like Trump assume total control. The poem opens with a sort of monologue in which the hero, Prometheus, is speaking to Jupiter (Zeus). Prometheus describes a world:

Made multitudinous with thy slaves, whom thou

Requitest for knee-worship, prayer, and praise,

And toil, and hecatombs of broken hearts,

With fear and self-contempt and barren hope.

There are some wonderful touches here and does the description of Jupiter not fit the thin-skinned, praise-seeking Trump perfectly? What a great phrase: “knee-worship” -- is that not exactly what Trump seeks from his “deplorables” in fact from all of us? And isn’t the phrase “hecatombs of broken hearts” gorgeous! The word hecatomb refers to an ancient Greek practice of sacrificing an enormous number of oxen and has come to mean an extensive loss of life for some cause. Here Shelley harnesses the term to conjure an image of a world filled with people who are afraid, who have given up and whose hearts are broken – pointless sacrificed.

The most important insight that comes, however, from Prometheus Unbound, is that we create our own monsters; that we enslave ourselves. And when we think of how Trump became President, I think it is important that we agree that in many ways we are all responsible for this.

Hotel Reigister from Chamonix in which Shelley declared himself to be an atheist and "lover of mankind."

Shelley had also famously declared that he was a "lover of humanity, a democrat and atheist.” I have written about this here and here. These are words of enormous power and significance; then as now. The words, "lover of humanity", however, deserve particular attention. Shelley did not write these words in English, he wrote them in Greek: 'philanthropos tropos". This was deliberate. The first use of this term appears in Aeschylus’ play “Prometheus Bound”. This was the ancient Greek play which Shelley was “answering” with his own masterpiece, Prometheus Unbound.

Aeschylus uses his newly coined word “philanthropos tropos” (humanity loving) to describe Prometheus. The word was picked up by Plato and came to be much commented upon, including by Bacon, one of Shelley’s favourite authors. Bacon considered philanthropy to be synonymous with "goodness", which he connected with Aristotle’s idea of “virtue”. Shelley must have known this and I believe this tells us that Shelley was self-identifying with his own poetic creation, Prometheus.

Shelley had deliberately, intentionally and provocatively “nailed his colours to the mast” knowing full well his words would be widely read and would inflame passions. So, when he wrote those words, what did he mean to say? He meant this I think:

I am against god.

I am against the king.

I am the modern Prometheus.

And I will steal the fire of the gods and I will bring down thrones and I will empower the people.

No wonder he was considered a threat.

Not only did he say these things, he developed a system to deliver on this promise.

Part of his system was based on his innate skepticism, of which he was a surprisingly sophisticated practitioner. And like all skeptics since the dawn of history, he used it to undermine authority and attack truth claims. As he once said, "Implicit faith and fearless inquiry have in all ages been irreconcilable enemies. Unrestrained philosophy in every age opposed itself to the reveries of credulity and fanaticism."

Let us now talk a little about his political theory and bring ourselves up to the present.

"And who are those chained to the car?" "The Wise,

"The great, the unforgotten: they who wore

Mitres & helms & crowns, or wreathes of light,

Signs of thought's empire over thought; their lore

"Taught them not this—to know themselves; their might

Could not repress the mutiny within,

And for the morn of truth they feigned, deep night

"Caught them ere evening."

Triumph of Life 208 – 15

These words are from his last great poem. We see in this passage a succession of military, civil and political leaders all chained to a triumphal car of the sort Roman generals were fond using when they celebrated victory.

The triumph of Lucius Aemellias Paullus

But Shelley adds a twist. In his poem, these rulers are now themselves slaves. This helps us understand a curious idea of Shelley’s which has confused many of his readers. And that is the idea that the tyrant who enslaves men is himself becomes a slave. This is because they are slaves to all their baser instincts. We can clearly see Trump in this picture. As the character Asia shrewdly notes in Act II of Prometheus Unbound: “All spirits are enslaved who serve things evil.”

Now, Shelley saw a way to avoid this. And it is tied closely to his theory of the imagination and his understanding of the nature of people. Shelley believed that we did not have to be slaves of our baser instincts the way Trump is. His cure is the education of the imagination; something it is difficult to imagine Trump having ever undertaken as it is widely believed he has almost never read a book.

The great Shelley scholar, PMS Dawson wrote that Shelley believed “the world must be transformed in imagination before it can be changed politically.” This imaginative recreation of existence is, said Dawson, both the subject and the intended effect of Prometheus Unbound.

This is a wonderful idea: Shelley’s poem not only maps out a scheme to reinvent ourselves and therefore change to world, but also, simply by reading the poem we will have started out on our journey. This underlines the importance of the arts to making our world a better place. I think of Obama’s statements about the importance of books to him while he held the presidency. And then I think of the rumours that Trump intends to act to wipe out support for the arts. I think of the manner in which the right wing cyberlibertarian “religion” of silicon valley has attacked the very foundation of art – the ability of our creators to earn a decent living.

One of the central teachings of Prometheus Unbound then is that only someone devoid of the liberty of self-rule can become a tyrant and enslave others. Gaining control over our baser instincts therefore becomes central to the advancement of society (this also explains why Shelley clung so tenaciously to his idea of the perfectability of humanity. In Act III of the poem we clearly see the protagonist’s ascent to the “autonomy of self-rule” as an example for mankind to follow.

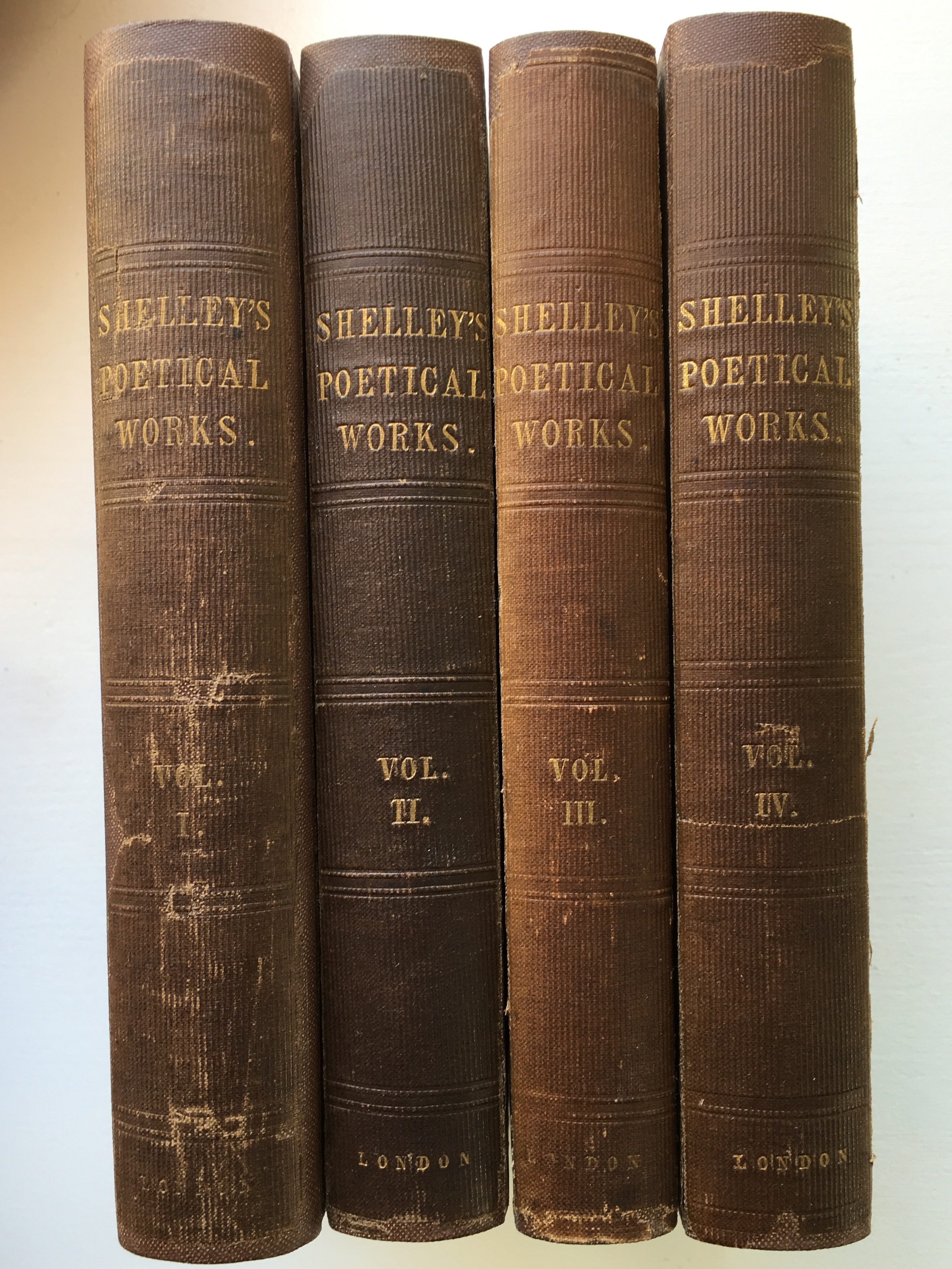

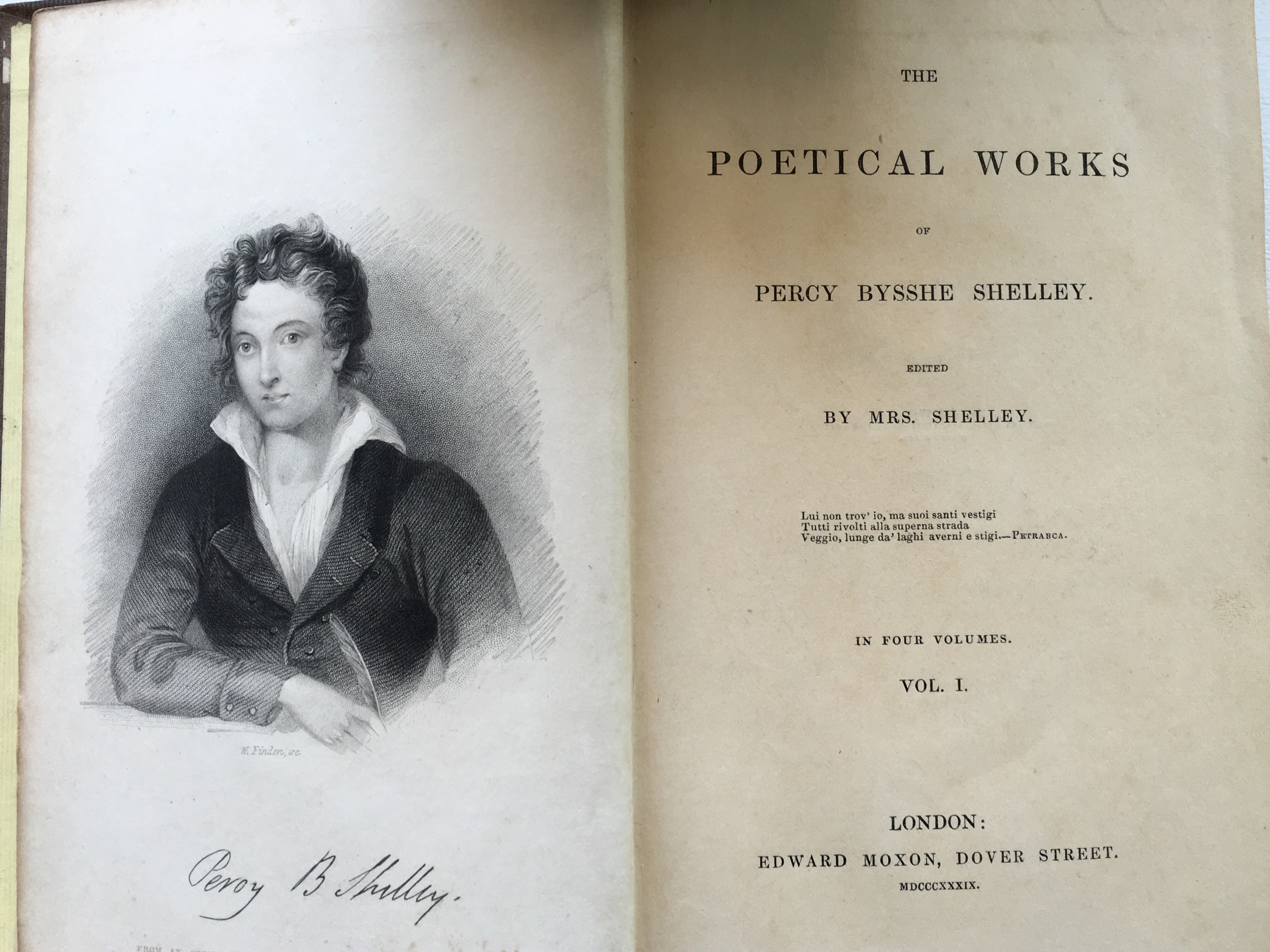

Finden's reimagining of Shelley drawn from the Curran portrait.

Shelley’s purpose in all his poetry is to help us (or cause us) to enlarge our imaginative apprehension of the world to such a point that there are no limits or inescapable evils. I think he believed that this is the role of all art. We need to be able to see different worlds, alternate worlds so that we can order our own world more equitably. Contrast this with Trump’s barbaric cry that America is only for Americans and that he will implement strategies which will benefit only Americans. This type of xenophobia, coupled with what amounts to a war on knowledge and the arts, is designed to create an environment in which tyranny becomes perpetual.

Shelley, however, is not a poet of gloom and dystopia. Shelley believed in humanity, he believed that we all have in us the power to be better and to make a better world. Indeed, the whole of Act 4 of Prometheus Unbound celebrates man’s birth into a universe that is alive because it is apprehended imaginatively.

Shelley did not, however think this would happen overnight. He was a gradualist, though I think even he would be surprised at just how gradual change can be. I often think that the thing which would shock him most about our modern world is not rockets and computers, but the fact we are still living in a priest and tyrant ridden world in which wealth is concentrated more than ever in a few hands. But he also believed that in moments of crisis, progress can emerge from conflict. Which is exactly where we are now. Exactly how we extract progress from our current crisis is up to us.

But I hope that we can see a glimpse of the future in these extraordinary pictures from around the world of the massive women's marches. Women are employing the very tactics that Shelley proposed two centuries ago:

'And these words shall then become

Like Oppression's thundered doom

Ringing through each heart and brain,

Heard again-again-again-

'Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number-

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you-

Ye are many-they are few.'

These words have inspired generation of protesters and leaders, including Gandhi. Today, as Freedland also points out, the threats are so multifaceted that they threaten to overwhelm us. As facile as this might sound, I think we need to believe in ourselves and in human nature. We need to resist, we need to organize, we need to keep the arts alive. It will not be easy. This is a theme explored by Michael Demson in his graphic novel that celebrated Shelley other great political poem, The Mask of Anarchy. I reviewed it here.

At the end of Prometheus Unbound come three stanzas of the most exquisite poetry ever written. In the first stanza Shelley forecasts the end of tyranny. He sees an abyss that yawns and swallows up despotism. And he sees love as transcendent. Now the moment we start to talk about the role of "love" in this I think some people might roll their eyes. But don’t. Shelley is thinking more about empathy than romantic love here. And nurturing empathy within us may be one of the greatest challenges our time. Certainly, Trump and his “lovely deplorables” have utterly failed in this regard. Shelley then goes on to itemize the psychological characteristics which will ensure that the tyrant once deposed, does not return.

Shelley imagines a radical reordering of our world. It starts with us. Are we up for the challenge? Shelley was. Take the closing words of Prometheus Unbound and print them out. Pin them to your fridge, memorize them, share them with loved ones and enemies alike. Let them inspire you. Let them change you. And never forget he was 27 when he wrote these words and dead with in three years:

This is the day, which down the void abysm

At the Earth-born's spell yawns for Heaven's despotism,

And Conquest is dragged captive through the deep:

Love, from its awful throne of patient power

In the wise heart, from the last giddy hour

Of dread endurance, from the slippery, steep,

And narrow verge of crag-like agony, springs

And folds over the world its healing wings.

Gentleness, Virtue, Wisdom, and Endurance,

These are the seals of that most firm assurance

Which bars the pit over Destruction's strength;

And if, with infirm hand, Eternity,

Mother of many acts and hours, should free

The serpent that would clasp her with his length;

These are the spells by which to reassume

An empire o'er the disentangled doom.

To suffer woes which Hope thinks infinite;

To forgive wrongs darker than death or night;

To defy Power, which seems omnipotent;

To love, and bear; to hope till Hope creates

From its own wreck the thing it contemplates;

Neither to change, nor falter, nor repent;

This, like thy glory, Titan, is to be

Good, great and joyous, beautiful and free;

This is alone Life, Joy, Empire, and Victory.

Shelley's poetry has changed the world before; let them change it again.

What Shelley, Star Trek and Buffy The Vampire Slayer Have in Common: Humanism!!

Shelley was after all, the man who, translating Lucretius, wrote, “I tell of great matters, and I shall go on to free men's minds from the crippling bonds of superstition.” However, were Shelley "beamed" to the present by Scotty, I think he would be very surprised to learn that "belief in the supernatural" was not already a thing of the past. He would be shocked to see the humanist agenda in retreat not in the face of benign, religious belief systems, but rather radical, intolerant, orthodox fundamentalism of all varieties. I think he would be profoundly unsettled by the realization that 200 years after the publication of Frankenstein and Prometheus Unbound, a secular, humanistic society was still an imagined future that was the subject of science fiction.

I offer a very short post today on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of one of the few GREAT humanist television programmes. Now, I will admit off the top, that I am a huge fan and always have been. But until today, I am not sure I made the connection between Shelley and Star Trek. But now I know what it is - both Shelley and Star Trek's creator, Gene Roddenberry were humanists to the core.

There is nice article on the subject of Star Trek's humanistic vision by the CEO of the British Humanist Association, Andrew Copson which can be found here. The BHA is a terrific organization that among other things sponsors a programme of annual lectures that explores humanism and humanist thought as expressed through literature and culture. The 2016 Darwin Day lecture, for example, was given by the redoubtable Jerry Coyne. Coyne, an indefatigable advocate for evolution and atheism, is also a fan of Shelley, and made these comments about him in a recent article:

Shelley could be seen as the first “New Atheist,” since he argued that the idea of God should be seen one that requires supporting evidence. The frontispiece of my book Faith Versus Fact starts with a quote from the 1813 edition of the pamphlet:“God is an hypothesis, and, as such, stands in need of proof: the onus probandi [burden of proof] rests on the theist.”

One of the characteristics of “New Atheists”, as I see it, is their framing of religious “truths” as questions subject to empirical and rational examination (i.e., science construed broadly). Although Shelley wasn’t a scientist, I adopted him as an Honorary Scientist (and honorary New Atheist) for making the statement above.

Coyne has also spoken admiringly of and drawn attention to this blog, for which I am grateful.