The Illusion of Free Stuff by David Newhoff

I find it interesting that as angry as we seem to be over ceding political power to corporate interests because they can buy influence, that we are unwittingly going to cede cultural power as well, simply by abdicating our ability to vote with our pocketbooks.

Today my Guest Contributors section pivots away from Shelley and looks to music. One of the true deep thinkers on the interface between the creative community and technology is David Newhoff. David spent over 2 decades working in corporate communications for many clients of every size but of late has transferred his very considerable intelligence to writing and developing theatrical film projects. In his own words, "As an artist, a writer, and a professional in the field of communications, I have always been fascinated by broad subjects related to human psychology, politics, epistemology, history, and of course the matter of whether we’re using technology or it’s using us."

A few years ago, David also began "thinking about a project that would investigate the matter of how well we’ve lived up to the highest aims of the digital age." And so, The Illusion of More as a blog site, was born. I have followed David's writing for many years now. I finally have the chance to help spread the word about him. Today I am offering readers a reprint of an article of his that appeared at IOM in 2014. The fact that it is re-publishable today speaks volumes about the prescience of his writing. Having said that, this site actually specializes in bring to life ideas from years past!!

I have always believed that "free" was an enemy of creativity. I would often say that consumers of content in the digital era should be careful what they wished for. The only real alternative to paying for something yourself is that someone ELSE has to pay for it. Radio is a perfect example of such a model. It is virtually entirely supported by advertising. The consumer "pays" for the product because the cost of the advertising is built into the price of products they purchase. "Free" accordingly, is an illusion. If we place the choice about what does or does not get published into the hands of advertisers, we are most definitely abdicating responsibility for the choice about what we get to read and or listen to. Today many people the world over clamor to get creative cultural products for free. Let's see what David has to say about the subject.

Please follow David in Twitter @illusionofmore and visit his most excellent blog here.

The Illusion of Free Stuff

Yesterday’s New York Times offers a very well-articulated editorial by media writer David Carr on the larger economic cost of free media. Using an example of buying fresh fruit at a neighborhood stand, Carr questions his own instinct to undervalue the price of a bunch of grapes in context to the way in which so much access to “free stuff” has skewed his own perceived value of goods and services in general. In a market like ours, value is reflected as price and always traces back to labor, someone’s labor somewhere. So, I think Carr is right to ask whether or not the steady stream of free stuff in digital space corrupts our perception of value in other sectors of the economy, which can only have a cannibalizing effect on the value of our own labors whatever they may be.

We are taught in basic economics that goods have intrinsic value (i.e. cost of production + some margin of profit), and that they have perceived value (i.e. what the market will bear), with perceived value determining how wide that margin of profit can be. I never formally studied economics, but it seems to me that when perceived value drops below intrinsic value, prices become “artificially” low in the sense that what the market will bear can no longer sustain production of the goods in question. This, of course, depends partly on one’s definition of “sustainability.” If, for instance, the price of socks at Walmart is “artificially” low because it can only be sustained by outsourcing sock production to a country with poverty-level wages and few workers rights, then this is certainly one kind of sustainability, but it is one that includes hidden costs we privileged consumers tend to ignore until it affects us directly. The closer it gets to home (e.g. when we read about Walmart’s own employees working below the poverty line), we pay a little more attention. A little. And of course, prices can also be made artificially high based on perceived value. As anyone who’s ever marketed luxury goods can tell you, a wealthy buyer’s ego is worth several percentage points of mark-up.

One can extol the virtues of technology, invoke examples of historic transformations like the printing press, and cry Progress! from the rooftops in stream-of-consciousness editorials like this one by Bob Leftsetz, whose criticism of Carr reminds me of a slightly demented Kerouac, if Kerouac had hated music. But if we clear away the smoke and dust from all that bluster, we might address the central point which is that the perceived value of a song (and we’ll let song stand for all media) has unquestionably reduced prices (or rates) to unsustainable levels for supporting the production of music itself. So, the consequential question is whether or not we actually care. Quite simply, the perceived value of recorded music was first reduced to zero by piracy (which is neither economic nor technological progress), then it was briefly and only partly resuscitated by digital downloads, and then it was dropped back to effectively zero by streaming services. And one reason we know the perceived price is zero or near zero is that so many tech-utopians keep saying it is while they offer numbskull suggestions like more merchandise, more touring, and “adding value” to replace the inescapable loss of revenue from disappearing sales.

When it comes to a products like albums or a motion pictures, prices are almost always flat so that the financial success of a given product is based entirely on volume of sales (i.e. popularity) and not on perceived or even intrinsic value (i.e. pricing) of each unique product. But in a technological paradigm that has driven prices in the entire category to zero or near zero, champions of the “new models” are quick to say that producers of media will share smaller bits of a much bigger pie because the Internet makes the whole world a potential customer for no more than it costs to reach a local market. Sounds good except for the fact that ten million times almost zero is still…y’know. This argument always reminds me of the old joke about the guy selling cord-wood for less than he buys it wholesale and figures the reason he’s losing money is that he needs a bigger truck.

But of course it’s all just progress, right? Technological innovations that improve efficiency and availability of goods always lower prices for consumers, and there is usually a period of revenue shift from one class of workers to another. It’s an unfortunate byproduct of change, but change is inevitable, so why shouldn’t we just embrace it and quit whining as Lefsetz and others insist we should? Because the transformation is not holistic and because the initial and persistent, catalytic force of piracy normalized a black market, with which no legitimate industry in any sector can ever compete. Both legal and illegal disruptions to media sales occur solely at the distribution end of the supply chain. If the Lefsetz-like utopians were to say that the folks who used to package and ship physical CDs are just victims of natural progress, I’d have to agree; but further upstream in the supply chain that ends with a song in your ear or a movie in front of your eyes is a production process where all the costly labor, expertise, and capital are invested. And when we devalue or become disconnected from the labor, expertise, and capital behind any product in any sector, this has that ripple effect to which I think Carr alludes in describing his gut reaction to the price of a pack of grapes.

Last week, songwriter/composer Van Dyke Parks wrote this editorial about the value of a song in the age of streaming, and I figured a guy like Lefsetz would go for the too-obvious criticism of this quote: “Forty years ago, co-writing a song with Ringo Starr would have provided me a house and a pool. Now, estimating 100,000 plays on Spotify, we guessed we’d split about $80.” The myopic reaction to a quote is to think either that a song should not be worth a house and a pool or that Parks and Starr have enough money; but both reactions entirely miss the economic implications of Parks’s point. If technological change drops the trade value of a popular good from a house and a pool to, say, a really nice car, then we might be looking at a modified but still sustainable market. But if the trade value of a popular good drops from house and pool to less than a basket of groceries, sustainability has been eradicated, and I personally think anyone who views this as virtuous is the same kind of fool as the guy in the joke hauling cord-wood.

Utopians like Lefsetz will say that the popular music and popular artists will still make plenty of money, and guys like Mike Masnick at Techdirt will preach the need for creators to embrace new lines of revenue. And indeed, both are right in a way I personally wish they were not. According to this brief post on Gawker, Grammy-winning pop star Pharrell not only performed at a recent Walmart shareholders meeting but apparently asked the crowd to “put your hands together for Walmart, guys, for making the world a happier place.” In light of Walmart’s track record for its labor practices, my friends and I twenty years ago would certainly have called Pharrell a sell-out. But today, anyone who loves free or almost free music and would still call him a sell-out is not only a tad hypocritical, but isn’t paying attention to what the market looks like when we break the transactional relationship between consumer and producer that ties price back to labor. Pharrell is just one example. We’re seeing a trend of popular artists take gigs to perform for sponsorships, corporate events, or private parties for wealthy individuals; and this move toward patronage by the elite is a direct response to the fact that we the people are no longer a source of revenue. This will probably have the unfortunate effect of turning executives at Walmart or Pfizer or Shell Oil into the new tastemakers, which just personally makes me miss even the sleaziest producer who ever worked for a record label. I don’t know whether or not a PR or communications person from Walmart fed that line about making the world happy to Pharrell, but my experience in corporate communications tells me it could have happened that way. What’s for sure is that such exchanges between execs and pop stars will happen soon, and the pop stars will no longer dictate terms to these big patrons, who are their only paying customers. I find it interesting that as angry as we seem to be over ceding political power to corporate interests because they can buy influence, that we are unwittingly going to cede cultural power as well, simply by abdicating our ability to vote with our pocketbooks.

The Illusion of Free was published by David Newhoff on 9 June 2014. You can find it at www.illusionofmore.com and by following this link.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works.

My Guest Contributor series continues with another article by Anna Mercer. Anna as readers of this space will known has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the British Association for Romantic Studies' the ‘On This Day’ blog. Anna discusses P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ and the inclusion of this poem in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. You can find the original post here.

I think this is an extremely important addition to the Guest Contributors series because it introduces the concept of collaboration. When I was a student in the 1970s and 80s, the idea that Mary had meaningfully collaborated with Shelley* on anything was unheard of. Indeed, the extent of Shelley's involvement in Frankenstein was poorly understood. The modern era has been, however, exceedingly kind to Mary and rather less so for for Shelley. As I have alluded to elsewhere, undergraduates around the world can be forgiven for being literally unaware of a personage by the name Percy Shelley; Mary is all anyone seems to talk about. While on the one hand this may be seen as an much overdue re-balancing of the scales of history, on the other it might be thought of as over-kill. This is where Anna comes in, guiding us through the complicated waters of one of the most interesting literary partnerships in the English language.

I think that today no one should approach the poetry of Shelley without understanding that these two creative people without question influenced one another. This will be a topic for one of my own blogs in the coming months, and I hope Anna will allow me to publish more of her work in this area in the future. Now, an area where Anna and I might disagree would be on the question of whether this poem offers evidence of philosophical idealism. My belief is that even by 1815, Shelley was such a thorough-going philosophical skeptic (in the tradition of Cicero, Hume and Drummond) that this is doubtful. This is, however, a quibble, and with that thought, let's turn to one of the modern experts on the subject of Shelleyan collaboration, Anna Mercer.

* A note on my choice of names. For most of the past two centuries, it has been common to refer to Mary Shelley as "Mary" and Percy Shelley as "Shelley". More recently many writers, such as Anna, now refer to them both by their given names. For my part, what matters is that fact that this is the manner in which they invariably referred to one an other; and so I stick with the old ways. I hope this will offend no one.

The Shelleys and "Mutability" by Anna Mercer

Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, from portraits in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

We are as clouds that veil the midnight moon;

How restlessly they speed, and gleam, and quiver,

Streaking the darkness radiantly!--yet soon

Night closes round, and they are lost forever:

Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings

Give various response to each varying blast,

To whose frail frame no second motion brings

One mood or modulation like the last.

We rest.--A dream has power to poison sleep;

We rise.--One wandering thought pollutes the day;

We feel, conceive or reason, laugh or weep;

Embrace fond woe, or cast our cares away:

It is the same!--For, be it joy or sorrow,

The path of its departure still is free:

Man's yesterday may ne'er be like his morrow;

Nought may endure but Mutability.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ is an example of his extraordinary poetic talent; in particular these lines show his ability to weave together philosophical ideas and striking imagery within a short section of verse. In this way the poem is reminiscent of Shelley’s famous sonnets such as ‘Ozymandias’ and ‘England in 1819’. However, ‘Mutability’ was written before these other works, which were composed in 1817 and 1819 respectively. The exact date of composition for ‘Mutability’ is not known: the editors of the Longman edition of The Poems of Shelley assign it to ‘winter 1815-16 mainly on grounds of stylistic maturity’. However, the opening lines ‘suggest a late autumn or winter night, but this could have been equally well a night in 1814’.

The ‘On This Day’ blog series thus far has focused on the bicentenaries of events from 1815: if the most likely dating for ‘Mutability’ places its composition in the winter of 1815, the poem must have lingered in the mind of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who would include lines from ‘Mutability’ in Chapter II, Vol II of Frankenstein (1818). Mary Shelley did not begin writing this novel (her first full-length work) until the summer of 1816, which she spent with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Claire Clairmont and John William Polidori in Geneva.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. Mont Blanc and the Glacier des Bossons from above Chamonix, dawn 1836.

It is interesting that we see Percy Shelley’s maturity emerging in ‘Mutability’, as the editors of the Longman Poems of Shelley establish. This maturity can be understood as Shelley’s fine-tuning of his philosophical expressions into a more coherent idealism. The poem’s almost universal application to any ‘man’ who lives on to the ‘morrow’ may be why Mary Shelley chose to place two stanzas (ll.9-16) in her first novel. They appear just before Victor Frankenstein reencounters his creation for the first time since its ‘birth’. He sets off on a precipitous mountain climb to the glaciers of Mont Blanc – alone – in an attempt to combat his anxiety and melancholy state of mind:

The sight of the awful and majestic in nature had indeed always the effect of solemnizing my mind, and causing me to forget the passing cares of life. I determined to go alone, for I was well acquainted with the path, and the presence of another would destroy the solitary grandeur of the scene.

Victor’s view of the valley, the ‘vast mists’, and the rain pouring from the dark sky, prompt him to lament the sensibility of human nature. As in P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’, the narrator considers the inconstancy of the mind. This meditation presents a powerful contradiction that inspires both hope and hopelessness by reminding the reader that a potential for change is always present, whether fortunes be good or bad, whether the individual is positively or negatively affected by his/her surroundings. Either way, all might be completely altered over a short space of time as the human mind responds to external influences. Just as Percy Shelley writes ‘Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; / Nought may endure but Mutability’, Mary Shelley’s protagonist considers how ‘If our impulses were confined to hunger, thirst, and desire, we might be nearly free; but now we are moved by every wind that blows, and a chance word or scene that that word may convey to us’. Lines 9-16 of Shelley’s poem are inserted in the novel after this sentence. Percy Shelley read and edited the draft of Mary’s Frankenstein, and Charles E. Robinson (editor of the Frankenstein manuscripts) has described the possibility of the Shelleys being ‘at work on the Notebooks at the same time, possibly sitting side by side and using the same pen and ink to draft the novel and at the same time to enter corrections’. The inclusion of the lines from ‘Mutability’ could even have been a joint decision.

Sir Walter Scott’s favourable review of Frankenstein from 1818 (when the novel was published anonymously) assumes this poetical insert to be the same authorial voice as its surrounding prose: ‘The following lines […] mark, we think, that the author possesses the same facility in expressing himself in verse as in prose.’ But instead, the implication is that Mary’s prose seamlessly leads into Percy Shelley’s verse, and illustrates the unity of their diction and their collaborative writing arrangement at this time.

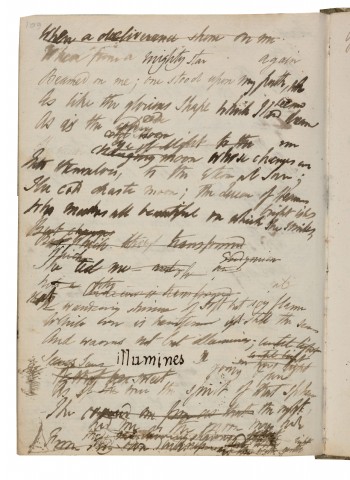

A page from Mary Shelley’s journal (1814) showing both Mary and Percy’s hands. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Mary Shelley’s journal shows that the Shelleys read S T Coleridge’s poems in 1815. Lines 5-8 of ‘Mutability’ indicate the possibility of a Coleridgean interest based on STC’s conversation poem ‘The Eolian Harp’. As Coleridge describes ‘the long sequacious notes’ which ‘Over delicious surges sink and rise’, Percy Shelley writes: ‘Or like forgotten lyres, whose dissonant strings / Give various response to each varying blast’. The Aeolian Harp or wind-harp (named after Eolus or Aeolus, classical god of the winds) is an image that reoccurs in Romantic poetry and prose. However it is significant that P B Shelley used it in common parlance with Mary, i.e. when writing letters. On 4 November 1814, he writes to her:

I am an harp [sic] responsive to every wind. The scented gale of summer can wake it to sweet melody, but rough cold blasts draw forth discordances & jarring sounds.

P B Shelley’s ‘Mutability’ can, in this way, promote discussion of the Shelleys’ creative collaboration. What we know of the Shelleys’ history provides evidence for their repeated intellectual interactions, as Mary Shelley’s journal shows an almost daily occurrence of shared reading, copying, writing and discussion. The Shelleys’ shared notebooks (not just the ones containing Frankenstein) also indicate that they would use the same paper to draft, redraft, correct and fair-copy their works. Beyond the Frankenstein notebooks, there are even instances of the Shelleys altering and/or influencing each other’s compositions in a reciprocal literary dialogue (something my work as a PhD candidate at the University of York is seeking to identify and explore in depth). If ‘Mutability’ was written in winter 1815 (or even earlier), maybe Mary Shelley looked over it, and kept it in mind in relation to her own creative writing – and therefore the poem found its way into her first novel. These details suggest that the Shelleys’ literary relationship was blossoming in the winter of 1815 (exactly 200 years ago), prior to their most significant collaboration on Frankenstein in 1816-1818.

References:

S. T. Coleridge, The Complete Poems ed. by William Keach (London: Penguin, 1997 repr. 2004) p. 87, 464.

Charles E. Robinson (ed.), ‘Introduction’ in Mary Shelley, The Frankenstein Notebooks Vol I (London: Garland, 1996), p. lxx.

Sir Walter Scott, ‘Remarks on Frankenstein’ in Mary Shelley: Bloom’s Classic Critical Views (New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008) p. 93.

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein: A Norton Critical Edition ed. by J. Paul Hunter (London: 1996 repr. 2012) pp. 65-67.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, ‘Mutability’ in The Poems of Shelley Vol I ed. by Geoffrey Matthews and Kelvin Everest (London: Longman, 1989) pp. 456-7.

William Godwin: Political Justice, Anarchism and the Romantics

Yet at least in the permanence of the printed word Godwin’s influence on Shelley remains. It is most apparent in Shelley’s political poems, which echo Godwin’s views on the state and his anarchistic vision of society.

Guest Contributors continues with Simon Court's brilliantly concise discussion of William Godwin's influence of the romantic poets. This account contains generous quotes from Godwin himself, and students of Shelley will no doubt hear much of Godwin in Shelley's poetry. But Godwin's influence was not limited to Shelley's political poetry, it can also be seen throughout Shelley's extensive philosophical prose.

Now having said that, it would be tempting to reduce Shelley's "intellectual system" to a rehashed amalgam of Godwin's thinking; many scholars have made this mistake. The fact is that while Shelley was influenced by Godwin, he a sophisticated philosopher in his own right - not an abject disciple. For example, Godwin had, as Simon points out, an incredibly "optimistic view of human nature." He quite literally believed that the world could be changed just by talking people into the change - no revolution required! He was a perfectibilist, and we can definitely see that tendency in the younger Shelley. But as Shelley grew in intellectual power, he came to see the world in a much more nuanced way.

As Terence Hoagwood points out, "Shelley advocates explicitly the active political displacement of [tyrannous structures] with another political structure: such a political advocacy is inimical to Godwin." (Hoagwood 6) Indeed, Prometheus Unbound also seems to point directly to some kind of revolution while veering away from any utopian resting place - both anathema to Godwin.

All of this is fodder for another blog post. For now, let's turn to Simon's account of Godwin's impact on Shelley and the Romantics. Remember: CONTEXT IS EVERYTHING!

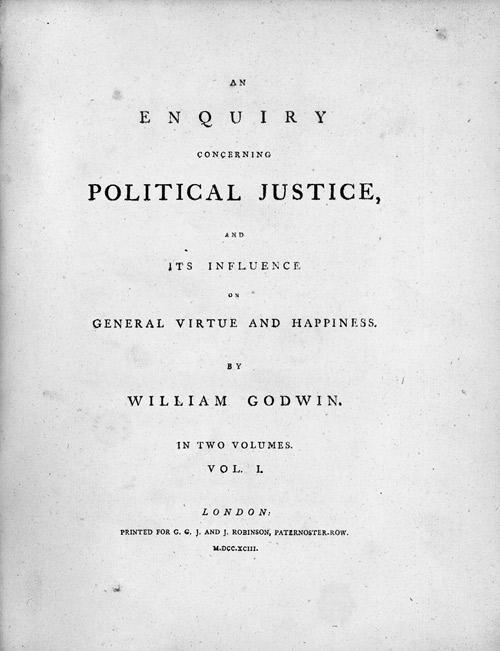

William Godwin: Political Justice, Anarchism and the Romantics, by Simon Court

William Godwin, painting by William Henry Pickersgill

William Godwin was a major contributor to the radicalism of the Romantic movement. A leading political theorist in his own right as the founder of anarchism, Godwin provided the Romantics with the central idea that man, once freed from all artificial political and social constraints, stood in perfect rational harmony with the world. In this natural state man could fully express himself. This idea was first articulated in An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, published in 1793, and was immediately seized upon by Coleridge as an inspiration for his misplaced venture into ‘pantisocracy’. Later, it heavily influenced Shelley in his political poems.

Mary Wollstonecraft, by John Opie, 1797

Godwin’s impact was personal as well as intellectual. He married Mary Wollstonecraft, whose Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) was one of the earliest feminist texts. He was good friends with Coleridge and later became the father-in-law of Shelley when his daughter, Mary, married the poet in 1816. Yet despite the idealistic ambitions of his principles, Godwin singularly failed to match up to them in his own life, behaving particularly hypocritically towards Mary and Shelley.

Godwin’s political views were based on an extremely optimistic view of human nature. He adopted, quite uncritically, the Enlightenment ideal of man as fully rational, and capable of perfection through reason. He assumed that “perfectibility is one of the most unequivocal characteristics of the human species, so that the political as well as the intellectual state of man may be presumed to be in the course of progressive improvement”. For Godwin, men were naturally benevolent creatures who become the more so with an ever greater application of rational principles to their lives. As human knowledge increases and becomes more widespread, through scientific and educational advance, the human condition necessarily progresses until men realise that rational co-operation with their fellows can be fully achieved without the need for state government. And, Godwin thinks, the end of the reliance on the state will also herald the disappearance of crime, violence, war and poverty. This belief in the inexorable perfectibility of man and progress towards self-government knew no bounds. Thus we find Godwin speculating that human beings may even eventually be able to stop the physical processes of fatigue and aging: for if the mind will one day become omnipotent, “why not over the matter of our own bodies….in a word, why may not man be one day immortal?”

On the other side of this sparkling coin lies the corrosive state, and here Godwin asserts that the central falsehood, perpetuated by governments themselves, is the belief that state control is necessary for human society to function. Rather, Godwin claims, once humanity has rid itself of the wholly artificial constraints placed upon it by the state, men will be free to live in peaceful harmony. For Godwin, “society is nothing more than an aggregation of individuals”, whereas “government is an evil, an usurpation upon the private judgement and individual conscience of mankind”. The abolition of political institutions would bring an end to distinct national identities and social classes, and remove the destructive passions of aggression and envy which are associated with them. Men will be restored to their natural condition of equality, and will be able to rebuild their societies in free and equal association, self-governed by reason alone.

Godwin’s utopian portrayal may be highly radical, but he was not a revolutionary. He believed political revolutions were always destructive, hateful and irrational – indeed, the immediate impulse to write Political Justice came from the murderous bloodshed in the recent French Revolution. And whilst Godwin never called himself an anarchist – for him, ‘anarchy’ had a negative meaning associated with French Revolutionary violence – his vision was recognisably anarchist. For Godwin, social progress could only be obtained through intellectual progress, which involved reflection and discussion. This is necessarily a peaceful process, where increasing numbers come to realise that the state is harmful and obstructive to their full development as rational creatures, and collectively decide to dissolve it. He was convinced that eventually, and inevitably, all political life will be structured around small groups living communally, which will choose to co-operate with other communities for larger economic purposes.

In addition to the artificial constraints placed on man by political institutions, Godwin identifies the private ownership of land, or what he termed “accumulated property”, as a major obstacle to human progress. And here, like all utopian thinkers, we find that Godwin’s criticism of the present reality proves to be far more convincing that his predictions of the future. For he observes that “the present system of property confers on one man immense wealth in consideration of the accident of his birth” whilst “the most industrious and active member of society is frequently with great difficulty able to keep his family from starving”. This economic injustice leads to an immoral dependence: “Observe the pauper fawning with abject vileness upon his rich benefactor, and speechless with sensations of gratitude for having received that, which he ought to have claimed with an erect mien, and with a consciousness that his claim was irresistible”. For Godwin, only the abolition of private property and the dismantling of the hereditary wealth which goes with it will free mankind from “brutality and ignorance”, “luxury” and the “narrowest selfishness”. Yet once freed:

Every man would have a frugal, yet wholesome diet, every man would go forth to that moderate exercise of his corporal functions that would give hilarity to the spirits: none would be made torpid with fatigue, but all would have leisure to cultivate the kindly and philanthropic affections of the soul, and let loose his faculties in the search of intellectual improvement. What a contrast does this scene present us with the present state of human society, where the peasant and the labourer work, till their understandings are benumbed with toil, their sinews contracted and made callous by being forever on the stretch, and their bodies invaded with infirmities and surrendered to an untimely grave?

In this utopia, or egalitarian arcadia, all the immoral vices of the present world, oppression, fraud, servility, selfishness and anxiety, are banished, and all men live “in the midst of plenty”, and equally share “the bounties of nature” – “No man being obliged to guard his little store, or provide with anxiety and pain for his restless wants, each would lose his own individual existence in the thought of the general good”, and “philanthropy would resume the empire which reason assigns her”. In this agrarian idyll, “the mathematician, the poet and the philosopher will derive a new stock of cheerfulness and energy from recurring labour that makes them feel they are men” (a world, incidentally, in which only “half an hour a day, seriously employed in manual labour by every member of the community, would sufficiently supply the whole with necessaries”).

Another highly radical idea raised by Godwin in Political Justice is the immorality of marriage. For Godwin:

“Co-habitation is not only an evil as it checks the independent progress of mind; it is also inconsistent with the imperfections and propensities of man. It is absurd to expect that the inclinations and wishes of two human beings should coincide through a long period of time. To oblige them to act and to live together, is to subject them to some inevitable portion of thwarting, bickering and unhappiness. This cannot be otherwise, so long as man has failed to reach the standard of absolute perfection.”

As such “the institution of marriage is a system of fraud”, and “the worst of all laws”. Moreover, “marriage is an affair of property, and the worst of all properties” (although this didn’t prevent Godwin marrying twice, first Mary Wollstonecraft in 1797 and then Mary Jane Clairmont in 1801). Inevitably, Godwin asserts, the institution of marriage will be abolished with all the other types of “accumulated property” in the new, free society. And although sexual relationships will continue because “the dictates of reason and duty“ will regulate the propagation of the species, “it will [not] be known in such a state of society who is the father of each individual child”, because “such knowledge will be of no importance”, with the “abolition of surnames”.

The vision of political society portrayed in Political Justice served as a direct and immediate inspiration for the Romantic ‘pantisocrats’ Coleridge and Southey, and contributed to their youthful flirtation throughout 1794 with the idea of migrating to North America to set up a rural commune (see Coleridge and the Pantisocratic pipe-dream). On a personal level, Coleridge first met Godwin and wrote the appreciative poem ‘To Godwin’ in 1794, but it was from 1799 onwards, when Godwin’s public reputation had waned, that they became good and mutually supportive friends (see Coleridge and Godwin: A Literary Friendship ).

By contrast, Shelley’s personal relationship with Godwin was far more turbulent: beginning in adoration but ending in despair. In 1811, Shelley started corresponding with Godwin, who was now a bookshop owner with a modest income, and offered himself as both an admirer and provider of financial support, which Godwin accepted in equal measure. A year later they met. Unsurprisingly, Shelley took Godwin’s pronouncements on marriage and ‘free-love’ to be a rational justification for him abandoning his first wife Harriet and eloping to Europe with Godwin’s sixteen-year-old daughter Mary, in July 1814. But Godwin reacted as furiously and as disapprovingly as any protective father would, and he refused to see Shelley and Mary on their return (whilst still being prepared to demand that money be sent to him under another name, to avoid scandal). By August 1820 Shelley was in such extreme debt himself, having previously obtained credit on the (false) assumption that he would soon inherit the family estate from his father, that he was finally forced to refuse Godwin’s constant demands for money, writing “I have given you ….the amount of a considerable fortune, & have destituted myself.” Within two years Shelley was dead.

Yet at least in the permanence of the printed word Godwin’s influence on Shelley remains. It is most apparent in Shelley’s political poems, which echo Godwin’s views on the state and his anarchistic vision of society. For instance, in The Masque of Anarchy (1819), which was written as a response to the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, Shelley describes how non-revolutionary, passive resistance can morally defeat tyrants, and how men can become free:

“Then they will return with shame,

To the place from which they came,

And the blood thus shed will speak

In hot blushes on their cheek:

Rise, like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number!

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you:

Ye are many – they are few!”

A tax lawyer by profession and living with a novelist and two cats, Simon Court indulges his passion for history by diving into the Bodleian Library at every opportunity. He has previously written about the English Civil War and has also written a biography of Henry VIII for the ‘History in an Hour’ series. When not immersed in the past he can be found in the here and now, watching Chelsea Football Club.

This post first appeared on the blog of the Wordsworth Trust on 4 October 2015

Works Cited

Hoagwood, Terrence. Skepticism and Ideology: Shelley's Political Prose and its Philosophical Context from Bacon to Marx. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1988. Print

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Revolutionary Ireland - by Sinéad Fitzgibbon

On the evening of 12 February 1812, Shelley arrived in Ireland after a long and difficult crossing, accompanied by his young wife, Harriet, and her sister, Eliza. Taking first-floor lodgings at 7 Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) in the centre of Dublin, Shelley turned his considerable energies to the task of finding a printer prepared to facilitate the publication of his recently-completed pamphlet, An Address to the Irish People. [You can find the text here] This was no small task considering the tract contained sentiments which could very well be viewed as seditious by the British authorities. Nonetheless, find a printer he did and by the end of his first week, Shelley had in his possession 1,500 copies of his address.

My Guest Contributors series continues with an excellent article by the prolific writer and blogger, Sinéad Fitzgibbon. Sinéad is a non-fiction author and literary critic. Her work has appeared in publications as diverse as the LA Review of Book's Marginalia Review, Books Ireland magazine, the Jewish Quarterly, and All About History magazine, among others. She also writes for the Wordsworth Trust's Romanticism blog. You can find her on Twitter, FaceBook and at her own blog spot, here. Sinéad's article on the revolutionary politics of the youthful Shelley provides an important foundation for everything that you will read in this space about Shelley. I make the point in my essay, "Shelley in the 21st Century" that Shelley's political and philosophical views are woefully misunderstood.

As recently as 1973, Kathleen Raine in Penguin’s “Poet to Poet” installment of Shelley omitted important poems such as Laon and Cythna as well as most of his overtly political output. And she did so with considerable gusto and stating explicitly that she did so “without regret”. In the most widely available edition of his poetry, the editor, Isabel Quigley, cheerfully notes, "No poet better repays cutting; no great poet was ever less worth reading in his entirety" and goes on to suggest, wrongly, that Shelley was a more than anything else a "Platonist'; somebody didn't do their homework.

In fact politics, as Timothy Webb has noted, was probably the dominating interest of Shelley's life; and his political engagement gets off to a roaring, if somewhat misfiring, start in 1812. If you intend to study Shelley, you better understand that and you better understand his philosophy or his "intellectual system", as he called it. Anna Mercer in her article "Teaching Percy Bysshe Shelley" writes, "If I teach a seminar exclusively on P. B. Shelley, the premise will be: read his prose, gather the philosophy, and understand how that is projected in verse in a way that is inimitable." Exactly, if only that were how he was taught.

And now on to the main attraction: Sinéad Fitzgibbon on Shelley and Revolutionary Ireland.

Sinéad Fitzgibbon

Ireland at the turn of the 19th century was a country in a state of flux. Tensions between the oppressed Catholic majority and the wealthy Anglo-Irish ruling class, known as the Protestant Ascendancy, had reached an all-time high. This was due in large part to the continuing existence of some onerous and prejudicial Penal Laws, which were a failed attempt by British authorities to extirpate the Roman religion from Irish shores. Consequently, republican sentiment, mainly among Catholics but also among a few liberal-minded Protestants, was on the rise as the disaffected population, inspired by the American War of Independence and the French Revolution, increasingly strained against the yoke of British rule. The year 1791 had seen the beginning of Society of United Irishmen, an organisation founded with the express aim of bringing liberty, fraternity, and equality to Irishmen of all creeds. The United Irishmen were not, however, to replicate the achievements of their French counterparts; a planned rebellion for May 1798 was foiled by the British authorities, and its leader, Theobald Wolfe Tone, was arrested and condemned to death.

Theobald Wolfe Tone, 1791

Politically, the reaction of the British Government to the growing republican threat was swift; the small degree of legislative independence enjoyed by Ireland was revoked, and the Irish Parliament in Dublin was disbanded by the Act of Union of 1801. Henceforth, Ireland was to be ruled directly from Westminster. In reaction to this, a militant nationalist by the name of Robert Emmet attempted to re-group and re-arm the United Irishmen and mount an attack on Dublin Castle, the organisational hub of British rule in Ireland. But this addendum to their story was to be short-lived. Emmet’s rebellion of 1803 was yet another failure and he too was to lose his life for treason. It was into this Ireland, riven with deep religious divides and trembling with frustrated republicanism, that the idealistic, nineteen-year-old Percy Bysshe Shelley sailed in 1812, determined to champion the cause of the subjugated Irish nation.

Dublin City Plan, 1812

It is difficult to say exactly when Shelley’s interest in Irish affairs was first awakened, although it was certainly in evidence before his expulsion from Oxford. There can, however, be no doubt as to why the plight of the Irish people so engaged him. Shelley was a radical thinker, an egalitarian dedicated to the cause of fairness, a second-generation Romantic hugely influenced by the liberal writings of the likes of Mary Wollstonecraft and Thomas Paine, and an avid disciple of William Godwin. In Ireland, he had a found a cause which appealed to his enlightenment sensibilities, representing as it did the quintessential struggle for justice and freedom.

On the evening of 12 February 1812, Shelley arrived in Ireland after a long and difficult crossing, accompanied by his young wife, Harriet, and her sister, Eliza. Taking first-floor lodgings at 7 Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) in the centre of Dublin, Shelley turned his considerable energies to the task of finding a printer prepared to facilitate the publication of his recently-completed pamphlet, An Address to the Irish People. [You can find the text here] This was no small task considering the tract contained sentiments which could very well be viewed as seditious by the British authorities. Nonetheless, find a printer he did and by the end of his first week, Shelley had in his possession 1,500 copies of his address.

Shelley's "Address to the Irish People", 1812

According to Harriet, Shelley took “great pains to circulate” his pamphlet. Unperturbed by the poor paper quality, the almost-illegible print, and the profusion of typos, copies were mailed to the homes of many of the country’s leading radicals and liberals. Others made their way to Shelley’s supporters and friends in England, including Godwin. About sixty were sent to pubs throughout Dublin, while the remainder were distributed by hand on the city’s crowded streets. With typical exuberance, Shelley even took to flinging some out of the window in Sackville Street onto the heads of passers-by below.

The young would-be revolutionary had high hopes that this treatise would make an impact on the people of Dublin, particularly on its target audience, the working class. In an advertisement taken out in the Dublin Evening Post, Shelley left the reader in no doubt as to the aims of his pamphlet; he declared that “…it is the intention of the Author to awaken in the minds of the Irish poor a knowledge of their real state, summarily pointing out the evils of that state, and suggesting rational means of remedy.” He counselled the country’s working classes to show restraint and toleration in their dealings with their Protestant masters, while also advocating a patient, measured and peaceful approach to their demands for emancipation. “Temperance, sobriety, charity and independence will give you virtue,” he insisted, “and reading, talking, thinking and searching will give you wisdom; when you have those things you may defy the tyrant.”

Shelley was, no doubt, entirely genuine in his desire to educate the ‘lower orders’ of Irish society on the realities of their oppressed situation, but in writing this pamphlet, he made two fundamentally erroneous assumptions. In the first instance, he took it for granted that the Irish poor needed to be told about the true nature of their oppression, and secondly, he failed to realise that they would hardly be prepared to accept instruction from a fresh-faced aristocratic Englishmen.

These were not the only problems with Shelley’s treatise. The condescending and sanctimonious tone was a miscalculation, as was its length – at twenty-two pages, the Address was far too long and verbose to hold the attentions of those he most wished to reach, despite his efforts to adopt a style that “the lowest comprehension could read.” It had also escaped Shelley’s notice that he was, in fact, preaching to the converted. The disastrous United Irishmen campaigns had convinced many in Ireland that militancy would not further the nationalist cause, and the tide of public opinion was already turning, with the help of the rabble-rousing Daniel O’Connell, to the idea of campaigning for parliamentary reform by means of purely peaceful political agitation.

Daniel O'Connell

Neither were Shelley’s politics without inherent contradiction; his stated admiration of the militant Robert Emmet (as espoused in the elegiac poem, On Robert Emmet’s Grave, most likely written during his visit to Dublin, and highlighted by his public visit to Emmet’s tomb in March) undermined the non-violent approach he advocated in his pamphlet. All in all, despite it being well-intentioned, An Address to the Irish People was seriously flawed, and although its author initially declared that it had “caused a sensation of wonder in Dublin,” its impact was negligible. Ultimately, it served only to highlight the naivety and confused principles of its author.

There was one upside, however; Shelley’s Address brought him to the attention of Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Committee, a group dedicated to the peaceful campaign for the abolishment of penal laws. He was invited to speak at a public meeting of the Committee on 28 February at the Fishamble Street Theatre, alongside O’Connell himself. Taking to the stage, Shelley spoke for over an hour, with much of his speech being a reiteration of the ideas expressed in his pamphlet. The reaction of the audience was equivocal, with Shelley himself admitting “my speech was misinterpreted… the hisses with which they greeted me when I spoke of religion were mixed with applause when I avowed my mission.” Nonetheless, he pressed ahead with the publication of two more pamphlets, Proposals for an Association (which called for the establishment of non-violent organisations for the advancement of political ideas) and a Declaration of Rights (copies of which were pasted all over the streets of Dublin). Neither publication was any more successful than his first effort.

The young poet must surely have been disappointed with Dublin’s lacklustre response to his revolutionary efforts. In the end though, it was William Godwin who proved to be Shelley harshest critic. While Godwin had disagreed with much of the content of An Address to the Irish People, he was horrified by Proposals for an Association, and strongly rebuked his protégé in a letter dated 18 March. “Shelley,” he wrote, “you are preparing a scene of blood! If your associations take effect […] tremendous consequences will follow, and hundreds, by their calamities and premature fate, will expiate your error.” This letter heightened Shelley’s growing sense of despondency, and finally convinced him of the futility of his Irish endeavours. He replied to Godwin, “I have withdrawn from circulation the publications wherein I erred & am preparing to leave Dublin.” And that, as they say, was that.

Percy, Harriet and Eliza left Dublin on 4 April 1812. While it might be tempting to say that Shelley’s first foray into real-life revolutionary politics was a failure, it would in reality be far too simplistic to do so. In the words of Shelley’s biographer, Richard Holmes, the young poet had arrived in Ireland as an ‘untested revolutionary’; over the course of his seven weeks in the country, he gained a harsh but valuable lesson in political reality. He left somewhat chastened, but very much the wiser. Indeed, it is a testament to his strength of character and his unshakeable belief in his principals that the Irish adventure did nothing to diminish Percy Bysshe Shelley’s enthusiasm for, and dedication to, the cause of justice, fairness and freedom.

This post was originally posted at The Wordsworth Trust blog on26th March 2014

Teaching Percy Bysshe Shelley, by Anna Mercer

As an undergraduate at the University of Liverpool, I was given A Defence of Poetry to read for a seminar that – and this sounds hyperbolic, but is in reality no exaggeration – I now realise in retrospect changed my life.

My Guest Contributor series continues with an article by Anna Mercer. Anna has studied at the University of Liverpool and the University of Cambridge. She is now in her third year as an AHRC-funded doctoral candidate at the Centre for Eighteenth Century Studies, University of York. Her research focuses on the collaborative literary relationship of Percy and Mary Shelley. She won the runner-up Keats-Shelley Prize in 2015 for her essay on the Shelleys, which has just been published in the Spring 2016 issue of the Keats-Shelley Review.

Anna has given me permission to reprint an article that was originally published as part of the ‘Teaching Romanticism’ series on Romantic Textualities. You can find Anna's own website here. Anna writes extensively on the Shelleys and her articles appear regularly on the web, including this gem from the blog at The Wordsworth Trust: "In the Footsteps of the Shelleys" Here she recounts a visit she made to Lerici, where Shelley died almost 200 years ago. I wasinterested in that post because my father had made a similar pilgrimage decades ago. I have an upcoming blog planned that will cover the peculiar circumstances of my father's and my own divergent interests in Shelley.

However, I am particularly interested in Anna's post here because it complements my own interest in how Shelley is taught. I believe Shelley (and Romantic studies) in general will need to undergo a virtual revolution if we are to start seeing him taught properly. You can find some of my own thoughts on this (and compare them to Anna's) in the Shelley Section in my article "Shelley in the 21st Century"

Here is her article:

I will be teaching undergraduates for the first time in Spring 2015. One anxiety I have is that new readers may come to the works of the ‘big’ Romantic poets with presumptions about their iconic status and therefore their work. Shelley has had perhaps one of the most unsettled critical histories of any Romantic figure: Matthew Arnold infamously branded him an ‘ineffectual angel’ in 1881, and although this misrepresentation has gradually and persistently been disproved in scholarship, the Romantics as a group of aristocratic, white, male, imaginative authors (of course, they all are not always these things, but Shelley is), writing 200 years ago, can sorely influence a new reader’s judgement of them. Surely it is important to establish that Shelley was actually philosophical, radical and political, as well as capable of writing beautiful verse effusions.

One of the critical minds responsible for establishing Shelley’s power was Kenneth Neill Cameron, who in 1942 wrote that ‘the key to the understanding of the poetry, in fact, is to be found in the prose’. More recent Shelley scholarship presents these works side by side, such as in the Norton critical editions. As an undergraduate at the University of Liverpool, I was given A Defence of Poetry to read for a seminar that – and this sounds hyperbolic, but is in reality no exaggeration – I now realise in retrospect changed my life. All of those famous phrases, ‘A Poet is a nightingale who sits in darkness, and sings to cheer its own solitude with sweet sounds; his auditors are as men entranced by the melody of an unseen musician, who feel that they are moved and softened, yet know not whence or why’, ‘for the mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness’, and of course, ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World’, struck me. I don’t believe I had any predetermined disposition towards Shelley and his writing; in fact, I knew nothing of Shelley before I picked up Duncan Wu’s excellent anthology for the first time as a nineteen year old, and I had never studied the long eighteenth century before.

Connecting prose with poetry in Romanticism is a critical understanding that is long established, obviously originating from the Romantics themselves. I do not know if the poems are taught in universities in isolation, but this should not be the case: and especially not with Shelley. Comparably, we know that one way of getting readers interested in the style of Lyrical Ballads is to read Wordsworth’s preface, or that to understand aspects of Coleridge’s poetics is to read the Biographia Literaria. Directing students towards Shelley’s prose gives them a wealth of understanding unparalleled by reading the verse alone, even with the abundance of criticism available.

As a research student, whose thesis focuses on both Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley, I have contemplated my aspiration to present these two inextricably linked authors in a way that is inspiring, equal, and above all relevant to (both of) their turbulent critical histories. It is appropriate here (and especially as I believe as both Shelleys should be read very closely together) to say that Frankenstein by Mary Shelley can be interpreted in such a vast variety of ways that the text occasionally eclipses its author’s voice: the notorious night of ghost story telling in Geneva in 1816 dominates perceptions of Mary Shelley’s creativity as a writer.

The relevant problem here is how then to introduce students to P. B. Shelley, whose reputation precedes him, both as a ‘Romantic’ poet, and as an individual present during that night in Geneva. The biographies of P. B. Shelley, and Mary Shelley, often overshadow the reason why they are established literary figures in the first place.

I do not pretend that the Shelleys’ turbulent lives did not in fact attract my own attention as a new literature student some years ago. Adolescent genius, forbidden love, undeniable intellect, and the combination of scholarship and drama contribute to the Shelleys’ intrigue. Yet Mary Shelley’s insight into her husband’s poetry is necessarily literary, and reminds us why we are interested in him at all: because of his poetic genius. In her 1839 Preface to P. B. Shelley’s Poetical Works, she explains how ‘his poems may be divided into two classes’:

"the purely imaginative, and those which sprung from the emotions of his heart. […] The second class is, of course, the more popular, as appealing at once to emotions common to us all."

This is the complexity of the poetry of P. B. Shelley, and what has to be conveyed to new readers. He can, in some verses, portray the beautiful in the everyday misery:

When the lamp is shattered

The light in the dust lies dead—

When the cloud is scattered

The rainbow’s glory is shed.

When the lute is broken,

Sweet tones are remembered not;

When the lips have spoken,

Loved accents are soon forgot. (‘When the Lamp is Shattered’, 1-8)

I remember hearing this poem for the first time in a lecture by Prof. Kelvin Everest; he explained its stunning intricacy as both relatable and idealistic. The poem on first reading has that Romantic simplicity from which the complexity must be extracted. It is therefore at once accessible and challenging. Shelley also has many poems, which are commonly misread assimply personal but in actuality are far more complicated than that.

Page from the original manuscript copy of Epipsychidion

The intense erotica of Epipsychidion, for example, is a unique anarchic poem of its times: ‘We shall become the same, we shall be one / Spirit within two frames’ (573-4). Anarchy leads us last, but not least, to Shelley’s political poetry, which reverberates through the public consciousness to this day. The Mask of Anarchy has become a powerful statement for the proletariat and the city of Manchester. Maxine Peake’s theatrical performance of the poem in 2013 exemplifies this. Examining these variants of P. B. Shelley’s poetry can deliver to a student the intrigue and unique power unrivaled in its particular diversity.

If I teach a seminar exclusively on P. B. Shelley, the premise will be: read his prose, gather the philosophy, and understand how that is projected in verse in a way that is inimitable. The beauty of teaching Shelley is that – I hope – you can take one sonnet, or even a short fragment, and the ‘power’ will be evident. The final lines of ‘Mont Blanc’ present in blank verse a stunning force by which the 23 year-old P. B. Shelley’s epistemology explores the relationship between mind and landscape. Addressing the mountain, he contemplates:

Mont Blanc yet gleams on high: – the power is there,

The still and solemn power of many sights,

And many sounds, and much of life and death.

In the calm darkness of the moonless nights,

In the lone glare of day, the snows descend

Upon that Mountain; none beholds them there,

Nor when the flakes burn in the sinking sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them: – Winds contend

Silently there, and heap the snow with breath

Rapid and strong, but silently! Its home

The voiceless lightning in these solitudes

Keeps innocently, and like vapour broods

Over the snow. The secret strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the infinite dome

Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!

And what were thou, and earth, and stars, and sea,

If to the human mind’s imaginings

Silence and solitude were vacancy? (127-144)

This article that was originally published on 12 March 2015 as part of the ‘Teaching Romanticism’ series on Romantic Textualities. It is reprinted with permission of the author and Romantic Textualities.

Frankenstein: Mystery, Monster, Myth - by Lynn Shepherd

In her poem The Choice Mary Shelley talks of the “strange Star” that had been “ascendant at [her] birth”, in a reference to the comet that had then been seen in the skies. Whatever “influence on earth” that particular celestial phenomenon might have exercised, I doubt any novel was ever conceived under a stranger star than her own “hideous progeny”, Frankenstein. And how familiar the tale of this tale now is.

This week I have the pleasure of introducing my Guest Contributor series with an article by Lynn Shepherd. I am particularly lucky because Lynn is a widely published and respected author who has kindly given me the permission to reprint one of her articles.

Lynn Shepherd graduated in English from Oxford in 1985 and then worked in London for five years before moving to Guinness PLC to work first in finance and then in public relations. During that time she created the Water of Life environmental and humanitarian programme, which is still running, and has brought clean drinking water to over five million people in Africa in the last five years alone.

She returned to Oxford for a doctorate in 2003, and during that time lectured on the 18th-century novel. Her thesis was published by Oxford University Press in 2009 as Clarissa's Painter: Portraiture, Illustration, and Representation in the Novels of Samuel Richardson.

Lynn is also the author of four novels, the award-winning Murder at Mansfield Park, Tom-All-Alone’s (The Solitary House in the US), and A Treacherous Likeness which is a fictionalised version of the dark and turbulent lives of Mary and Percy Shelley (published as A Fatal Likeness in the US). Her most recent book, The Pierced Heart, is inspired by Bram’s Stoker’s Dracula. She is a trustee of The Wordsworth Trust and runs their Romanticism blog.

Lynn Shepherd

“When I placed my head upon the pillow, I did not sleep…. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me…. I saw – with shut eyes but acute mental vision – I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world. … On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story….”

In her poem The Choice Mary Shelley talks of the “strange Star” that had been “ascendant at [her] birth”, in a reference to the comet that had then been seen in the skies. Whatever “influence on earth” that particular celestial phenomenon might have exercised, I doubt any novel was ever conceived under a stranger star than her own “hideous progeny”, Frankenstein. And how familiar the tale of this tale now is.

We are on the banks of Lake Geneva, in the summer of 1816. Wild storms have been raging about the Villa Diodati, and after a night telling ghost stories with Lord Byron, his doctor, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, the young poet who was soon to become her husband, the 18-year-old Mary Godwin has been disturbed by a chilling vision of a scientist destroyed by his own presumptuous ambition. It is a vision which will evolve eventually into Frankenstein, one of the most enduring novels of the 19th century, and the source of a terrifying modern myth. Mary’s account of its inception is so convincing that modern-day researchers have even attempted to date the precise hour of her vision by the appearance of the moon (between two and three in the morning of 16th June, according to one astronomer).

But is this really how the book came into being? The key point to remember here is that this account comes from a preface to the novel which was not added until 1831, some 15 years after the events described, by which time three of the four witnesses to Mary’s announcement were already dead – Byron of a fever in Greece, Shelley by drowning, and the doctor John William Polidori by his own hand. Who could have come forward to contradict her? Certainly not the one other person present that night: Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont, whose affair with Byron was at its height that summer. But what Mary couldn’t possibly have known was that Polidori kept his own account of those weeks at the Diodati – an account not published until 1911 – in which he makes no mention at all of Mary declaring to the company that she had “thought of a story”.

The ‘Frankenstein summer’ plays a central role in my own novel, and it is only one of many tantalising questions that still persist about Shelley’s book. Indeed, I have just raised one of the most intriguing of them in the very grammar of that last sentence. I called Frankenstein “Shelley’s book”, but which Shelley was it? Could a teenage girl, however well-educated, really have produced so powerful a story, especially when nothing she wrote in later life comes anywhere near it? And given that Percy Bysshe Shelley allowed his publisher to believe the book his own, and wrote a preface for it in 1818 which can scarcely be read any other way, surely he is by far the more credible candidate? You can certainly make the case for his authorship – and many people have.

Clearly we don’t know what early drafts of the book might have since been lost, but the manuscript that survives shows extensive changes and additions in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s hand; nor does the fact that the rest of it is in Mary’s writing prove anything in itself, since it could easily have been a fair copy of an earlier version, or one written to his dictation. The changes we see in the Bodleian Library manuscript show Percy making not just substantial but substantive amendments, sharpening the style and themes of the book in a way that tallies with what we know of his own preoccupations, and even his own history. For example, the horrifying vision of the monster at the window after Elizabeth’s death seems to be an uncanny echo of an episode in Shelley’s own life, long before he met Mary, when he was the victim of an apparent assassination attempt in Wales, and saw his assailant at the window. (Yet another incident in Shelley’s life which is fraught with unanswered questions, and another inspiration for my own novel).

Page from the manuscript of Frankenstein showing extent of collaboration between Mary and Percy. Percy's edits, additions and emendations are in darker ink. (On display at the Bodleian).

In her 1831 preface Mary insisted that “I certainly did not owe the suggestion of one incident, nor scarcely of one train of feeling, to my husband”, but one might well respond that surely she is protesting too much; in my own view the very least one can say is that Frankenstein was a creative collaboration. How far that extended – at what point ‘collaboration’ might have become ‘joint authorship’ – is a moot point, and one we are never likely to resolve barring the discovery of more documentary evidence. But what we do absolutely know, without question, is that Mary was not the sole and only author of this book.

The philosophical preoccupations of Frankenstein are certainly Shelleyan (and by that I mean him, not her). The novel’s subtitle is The Modern Prometheus, and Percy Bysshe Shelley later wrote a verse play Prometheus Unbound, taking the same mythical figure as his central character. The reference to Prometheus in Frankenstein evokes the theme of secret or forbidden knowledge which is picked up in the first pages of the framing narrative, where Walton’s desire to voyage to “lands never before imprinted by the foot of man” prefigures Frankenstein’s attempt to “unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation” and “pursue nature to her hiding-places”. The difference between them, of course, is that Walton seeks only to discover what is already there; Frankenstein, by deadly contrast, seeks to usurp the divine prerogative and fashion “a new species [which] would bless [him] as its creator”.

Frankenstein certainly generated one new species, a whole new genre of literature which we now call ‘science’ fiction, but the text itself is not much possessed by science. There is no attempt – not even much interest – in imagining how Frankenstein actually makes his monster. The novel concentrates instead on the moral and metaphysical consequences of such an act, and most particularly the responsibilities of the creator to the created, and the ties that bind them together which are “only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of [them]”. Indeed the plot is driven by Frankenstein’s attempt to escape, repudiate or destroy those ties, and the power and terror of the novel lies in the fact that the more he struggles to do so, the more inexorably he and his creature begin change places: the hideous monster becoming through the acquisition of language a “sensitive and rational animal”, while the honourable and gifted scientist degenerates into a “self-devoted” monster of egotism who either cannot or will not take responsibility for the murderous consequences of his own hubris. The irony here is incisive: Frankenstein rejects his creation as a “monstrous image… endued with the mockery of a soul”, but we perceive only too clearly that, like Adam fashioned in the image of God, this creature is indeed a “filthy type” of its creator, but one where the resemblance lies, in Spenser’s words, “not in outward shows, but inward thoughts“.

Dedication by Mary to Lord Byron of a copy of Frankenstein. (On Display at the Bodmer Foundation, Geneva)

Creature and creator alike become at the last outcasts, wandering the frozen northern wastes, and the monster that once pursued Frankenstein becomes in its turn the pursued. It is impossible, for me at least, to ignore the parallels here with Percy Bysshe Shelley – Percy Bysshe Shelley who described himself as “an exile & a Pariah” and “an outcast from human society”; Percy Bysshe Shelley who was obsessed by the idea of pursuit from an early age, and whose poetry is pervaded by what his biographer Richard Holmes calls “ghostly following figures” and dark demonic antitypes of the self.

Frankenstein is not without its (many) defects, and it may be worth pointing out that Percy Bysshe Shelley’s own youthful attempts at fiction are without exception deplorable. In Frankenstein, the insert narrative of Felix and the ‘Arabian’ is over-long, slows the pace, and adds very little; much of the language is ponderous; and the characters of Elizabeth and Frankenstein’s father little more than ciphers. The monster’s ability to acquire language to such a pitch of eloquence strains belief, and the construction of the plot relies far too heavily on improbable coincidence (as the writer Scott Pack’s publisher’s letter to Mary Shelley wittily observes).

It is flawed, yes, but it is also forceful and unforgettable. Because there are images and ideas here that will stay with you forever. The frozen plains of ice where Frankenstein hunts down his monster and sees “the print of his huge step on the white plain”; the creature’s awakening on that dreary November night when it first opens its “dull yellow eye”; the monster’s painful coming to consciousness and self-consciousness, and the tale it tells of how its natural “ardour for virtue” and desire for love is corrupted by the treatment it receives, and its brutal rejection by the one man who ought to have “render[ed] him happy”. And last, and above all, the way the book captures and articulates for the very first time what has since become perhaps the ultimate terror of the modern age: the power over life itself.

This post was originally written for the Writers’ Choice series run by the late Norman Geras and reposted to the Wordsworth Trust's blog on 1 January 2015

- Mary Shelley

- Frankenstein

- Mask of Anarchy

- Peterloo

- Anna Mercer

- Michael Demson

- William Godwin

- Coleridge

- An Address to the Irish People

- Byron

- Richard Carlile

- Jonathan Kerr

- Pauline Newman

- Mutability

- Epipsychidion

- Thomas Paine

- Mont Blanc

- Mark Summers

- Paul Foot

- George Bernard Shaw

- Chartism

- Diodati

- Timothy Webb

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Defence of Poetry

- William Wordsworth

- Queen Mab

- free media

- Daniel O'Connell

- Vindication of the Rights of Women

- Ginevra

- Jacqueline Mulhallen

- Edward Dowden

- Robert Southey

- Chamonix

- James Connolly

- Edward Aveling

- Claire Clairmont

- Levellers

- England in 1819

- Lynn Shepherd

- To Autumn

- Alastor

- Ozymandias

- Francis Burdett

- Kenneth Neill Cameron

- Thomas Kinsella

- Tess Martin

- Geneva

- Proposal for an Association

- Cenci

- Kathleen Raine

- Richard Emmet

- Martin Bodmer

- Sonia Liebknecht

- Radicalism

- Keats-Shelley Association

- Trotsky

- Isabel Quigley

- Alien

- Michael Gamer

- Maria Gisborne

- World Socialism Web Site

- Theobald Wolfe Tone

- Butcher's Dozen

- Percy Shelley

- Freidrich Engels

- Milton

- Blade Runner

- ararchism

- Paul Bond

- Rosa Luxemburg

- Masks of Anarchy

- Keats-Shelley Review

- John Keats

- Leigh Hunt

- A Defense of Poetry

- Humphry Davy

- perfectibility

- Henry Hunt

- Paradise Lost

- Political Justice

- Shelley Society

- Polidori

- Necessity of Atheism

- David Carr

- The Last Man

- Harriet Shelley

- Eleanor Marx

- Industrial Workers of the World

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Joe Hill

- The Easter Rising

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- Richard Margraff Turley

- Henry Salt

- Buxton Forman

- Lord Sidmouth

- Valperga

- Daisy Hay