Images and stories from around the world

AUDIO VISUAL PRESENTATIONS

Art in the Time of Pandemic

A short while ago, I sat down over a zoom call with the two masterminds behind a gorgeously shot 14 minute film that is a celebration and commemoration of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, Ode to the West Wind. It is called “Human O.A.K.”. An actor, producer and director, the multi-talented Ulisse Lendaro is the Italian creative genius behind the film. Lendaro’s co-production partner is Jitendra Mishra, a producer who has already been associated with the production, distribution and promotion of more than 100 films in different categories in various capacities. Many of them have received worldwide acclamation and recognition in global film festivals. For me it was a thrilling and inspirational conversation that was at times philosophical and at times profoundly emotional. Afterwards, Ulisse wrote me to say that our call had “quenched a thirst in my soul”. I share that emotion. I was so inspired by this conversation and what Lendaro has accomplished that I decided to go far beyond a typical interview and delve deeper into the topics we discussed. I hope you will enjoy what follows and become as inspired as I was. Together we can change our world for the better.

Ulisse Lendaro and Jitendra Mishra

A short while ago, I sat down over a zoom call with the two masterminds behind a gorgeously shot 14 minute film that is a celebration and commemoration of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, Ode to the West Wind. It is called “Human O.A.K.”. An actor, producer and director, the multi-talented Ulisse Lendaro is the Italian creative genius behind the film. Lendaro’s co-production partner is Jitendra Mishra, a producer who has already been associated with the production, distribution and promotion of more than 100 films in different categories in various capacities. Many of them have received worldwide acclamation and recognition in global film festivals. For me it was a thrilling and inspirational conversation that was at times philosophical and at times profoundly emotional. Afterwards, Ulisse wrote me to say that our call had “quenched a thirst in my soul”. I share that emotion. I was so inspired by this conversation and what Lendaro has accomplished that I decided to go far beyond a typical interview and delve deeper into the topics we discussed. I hope you will enjoy what follows and become as inspired as I was. Together we can change our world for the better.

Art in the Time of Pandemic

An Interview With Ulisse Lendaro and Jitendra Mishra

by Graham Henderson

Ulisse Lendaro is an Italian actor, producer and director now living in Vincenza. He first encountered the writing of Percy Bysshe Shelley in high school thanks to his French teacher - it left a profound impression (as Shelley can do!). Ten years later he revisited the poet and then again in 2020 when he was seeking inspiration for a short movie he wanted to make about the effect the pandemic was having on our lives. A very passionate, creative individual, Ulisse believes in the power of art to renew and advance the human race. In the midst of the current crisis he set himself the goal of making a film. He wanted to create a work of art which demonstrated our ability to reinvent and renew ourselves. Ulisse told me that he wanted to use a poem as the narrative foundation of his film - a poem which spoke to the possibilities for renewal and also which demonstrated the resilience of our species. Indeed, he hoped that the mere act of making this film would serve as a beacon of hope, telling me that creators are in effect at “the disposal of humanity to help create a better future”.

But where was he to start? “Believe me”, says Ulisse, “I looked everywhere: Italian poets as well as English poets like Byron and Keats and even Shakespeare.” This is when it occurred to him to look to Shelley. He quickly realized that it was only Shelley that inspired him. It was “the power of his poetry,” he said, “it speaks in a revolutionary way to our times. His words are also perfect for the cinema.” This is a topic I have written about many times. And the poem he settled on was Ode to the West Wind - a poem enjoying its 200th anniversary just now.

Ulisse with his wife Anna Valle and children Ginevra and Leonardo (all of whom appear in the film).

Ulisse went about his task with his characteristic passion and thoroughness. He immersed himself in Shelley’s poetry and his life. Soon his entire family was reading Shelley’s poetry and experiencing the power of the poet’s words to do something Ulisse found quite remarkable - as he put it: “to influence people from generation to generation to generation.” Like me, Ulisse marvelled at Shelley’s fervent desire to change the world through a revolution of the imagination. As Ulisse remarked,

“I read Shelley at different times in my life and he always fascinated me because his poems always acquire new and relevant revolutionary meanings. Shelley was a visionary dealing with universal themes and that's why I think he is so very contemporary.”

“I read Shelley at different times in my life and he always fascinated me because his poems always acquire new and relevant revolutionary meanings — Ulisse Lendaro”

This led Ulisse and I into a discussion about Shelley’s theory of the “cultivation” of the imagination as a moral power — something that sets him apart from all other Romantic writers. A lot of ink has been spilled over what the term “cultivated imagination” actually means, but I think Shelley’s theory was expansive enough to allow for many different coherent explanations.

For me it starts with Shelley’s aversion to the authoritarian political systems with which he was all too familiar. And, much like the Deists of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Shelley looked upon established religion as an enabler of those structures and he looked upon religious faith as little more than superstition. “Religion,” he said, “is the handmaiden of tyranny.” To attack these structures, Shelley relied on skepticism - an ideal tool to undermine entrenched power structures of any kind and in particular religion. Put simply he advocated questioning and undermining all authority.

To replace these structures was an entirely more difficult problem, and one which Shelley would rely on a different programme. Shelley talks and writes a lot about love - to the point that many people think of him primarily as a love poet - a writer of harmless romantic poetry. And indeed, Shelley frequently wrote about romantic love and also sexual love. But mostly when Shelley talked about “love” he was very clearly thinking about that psychological capacity that would come to be known as “empathy”: the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another person. This alone would not suffice for Shelley, however, because Shelley wanted to change the world, to make it better, to help people, and so Shelley’s empathy is always infused with compassion. To change the world, he thought, required an imaginative revolution; people had to learn to see the world very differently - but how? I think of his response to Coleridge’s partially plagiarized poem about Mont Blanc, “Hymn Before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni”:

Ye Ice-falls! ye that from the mountain’s brow

Down enormous ravines slope amain --

Torrents, methinks, that heard a mighty voice,

And stopped at once amid their maddest plunge!

Motionless torrents! silent cataracts!

Who made you glorious as the gates of Heaven

Beneath the keen full moon? Who bade the sun

Clothe you with rainbows? Who, with living flowers

Of loveliest blue, spread garlands at your feet?—

God! let the torrents, like a shout of nations,

Answer! and let the ice-plains echo, God!

God! sing ye meadow-streams with gladsome voice!

Ye pine-groves, with your soft and soul-like sounds!

And they too have a voice, yon piles of snow,

And in their perilous fall shall thunder, God!

Like most of his era, Coleridge believed that God was responsible for all that is beautiful and sublime in our world. In this poem he challenges his readers to look at the natural world and not see the handiwork of god. Shelley, writing his own poem dedicated to Mont Blanc some years later, accepted this challenge and tacitly denounced Coleridge’s worldview. Whatever you think about the plagiarism charge, one thing we do know, Coleridge was never in the “Vale of Chamouni”, he never actually saw Mont Blanc - Shelley was and did. Shelley believed it was essential that we look not for “hand of god” in our lives and demanded that we assume responsibility for not only our actions but the world in which we live. To rely on superstition and external powers is to shirk personal responsibility for our lives.

But to actually see the world differently would require a cultivated imagination that could break the great chain of superstition and reliance on “faith” which inhibits our imagination and holds us hostage to the past. And such an imagination is only possible if we adopt a skeptical view of accepted dogmas and entrenched institutions and cultivate our powers of empathy and compassion. The best way to do that is really quite straightforward - it is done through immersing yourself in the lives and experiences of others - something that can be done though experiencing art in all its formats; I would argue particularly, reading. Ulisse agreed. “I think this is very important,” he said because this is in fact the theme of his film:

“The Oak tree represents the family tree of humanity - it is to this that the little girl in the film is drawn. And it is through literature that she can experience not only the past but the future as well. Reading, literature and art, is the bridge between the past and our future. This is how humanity can regenerate and renew itself.”

“Reading, literature and art, is the bridge between the past and our future. This is how humanity can regenerate and renew itself. — Ulisse Lendaro”

It was for this reason Ulisse selected Ode to the West Wind. A deeply personal poem, the Ode central metaphor is the wind. As Paul Foot noted, “the wind, and everything associated with it, became a series of shifting symbols each connected with Shelley’s ideas [and] his revolutionary inspiration….” The same is true for Ulisse’s cinematic realization of Shelley’s poem. In the film, the wind is the protagonist, a silent, observing presence that interacts with the actors. Shelley’s poem is somewhat despairing. He regrets the ideals of his youth for revolutionary change seem to be ever more out of his grasp. Yet, the poem ends with a call to the wind which he wants to maintain and spread the revolutionary spirit of his words in what Foot called a “mighty agitation which would reach and awaken all humanity.”

Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like wither'd leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish'd hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken'd earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?

His invocation has been answered; though ignored, censored and outcast in his own time, Shelley’s poetry went on to inspire generations of enthusiasts, activists and creators - including Ulisse whose film is a literal response to Shelley’s closing stanzas. I find Ulisse’s reinterpretation of Shelley’s masterpiece to be altogether uplifting and full of hope. Shelley would be profoundly gratified. You will need to see for yourself the manner in which Ulisse has developed the Shelley’s ideas.

Ursula K. Le Guin.

I reminded Ulisse of Shelley’s famous remark in The Defense of Poetry: “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” I have always unpacked this to mean that creators are the representatives of the people. and that their works incarnation of the hopes and desires of humanity. Take this a step further and what Shelley seems to be saying is that creators speak for the people and are therefore an essential if not critical component of the political system. It also makes them a formidable foe of authoritarians, which probably explains why they view writers in particular as such a threat — and often imprison or even kill them. As Ursula Le Guin once remarked, “Dictators fear poets.” My friend Ciaran O’Rourke defined this role particularly well, in his article Shelley in a Revolutionary World, he wrote of James Connolly the famous Irish republican and socialist:

“If Shelley conceived of poets as the unacknowledged legislators of the world”, a great part and purpose of this role lay, for him, in the capacity to perceive and express the radical aspirations of the toiling “many” (in Ireland and farther afield)”.

One of Le Guin’s other well known statements was that “we read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel… is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.” Remarks like this are why I believe Le Guin was a Shelleyan through and through. Her thinking her almost exactly aligns with Shelley - and Ulisse as well — in his film, literature (specifically books), play an essential role in his vision of the renewal of humanity.

“We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel… is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become. — Ursula K. Le Guin”

All of this put the importance of creators in our society in the front and center of our minds, and so our conversation turned to the plight of creators today in the wake of the pandemic. Ulisse talked about dancers he knew who were now unable to dance, shuttered theaters and out of work actors. I pointed to the music community where an entire way of life has been almost destroyed. While both Ulisse and I agreed that art forms such as music and theater will never die, neither of us fully understand what it is into which they will morph.

Something else is clear as well, during the current crisis, the rich are getting fabulously wealthy and the middle class and the poor are being squeezed. This form of inequity is exactly what Shelley himself railed against two hundred years ago. I have often said that I think the things that would shock Shelley the most were he to time travel to our time would not be computers and rockets, but rather that the share of wealth concentrated in the hands of the few has become even greater. He would have expected better of humanity after the passage of two hundred years. We should be ashamed. If Shelley and Ulisse are right about the role of the creator in shaping our future (in fueling our resistance, our renewal and our resilience) then it really feels like the survival of the artistic community becomes increasingly important.

Rabindranath Tagore. 1861 - 1941

There was another undercurrent to our conversation and that is the Indian connection here. Jitendra, Ulisse’s affable, thoughtful production partner remarked that there was in fact strong link between his country and Shelley. I pointed out that Shelley was actually extremely interested in Indian art and poetry. He had read extensively about India and the imagery in Prometheus Unbound was heavily influenced by mythological motifs drawn from there - Stuart Curran writes extensively about this in his book “Shelley’s Annus Mirabilis”. Toward the end of his life he wrote to Hogg remarking that he was thinking of going to India "where I might be compelled to active exertion and enter into an entirely new sphere of action". Later however, he despondently wrote to Byron saying "I feel sensibly the weariness and sorrow of past life.” The idea of doing something new in India had become for him, "I dare say a mere dream".

Jitendra responded by pointing out the fact that Gandhi was fond of quoting lines from The Mask of Anarchy. Shelley, as is well known, was one of the very first writers to express the idea that the most effective response to oppression and force was massive, non-violent resistance. We can not underestimate exactly how revolutionary that would have seemed at the time. Some have guessed that Shelley’s ideas may have been transmitted to Gandhi during the time he spent in England; possibly through the medium of Henry Salt. But the link has never been established. What we can say is that Shelley and Ghandi shared a particular outlook on life at least insofar as pacifism is concerned.

Another influential Indian thinker who was certainly aware of and influenced by Shelley was Rabindranath Tagore (1861 - 1941). He was sometimes described as the “Bengali Shelley” for reasons even a cursory examination of his biography will make plain. The first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (1913), Tagore was a Bengali poet, short-story writer, song composer, playwright, essayist, and painter who was highly influential in introducing Indian culture to the west and vice versa. However, the connection that interested Jitendra the most was between the Tamil poet Subramania Bharati (1882 - 1921) and Shelley. Bharati is perhaps one of India’s most famous poets (and one of the least known outside of its borders). Bharati was phenomenally prolific and influential - he was also a nationalist and revolutionary in his outlook. And one thing we know for certain - he was profoundly influenced by Shelley - to the point he adopted the pen name “Shelley-Dasan” - meaning “disciple of Shelley”. One of his poems, entitled “Wind”, appears to be designed as a meditation on and reinterpretation of Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind. It is infused with a Shelleyan revolutionary spirit - a spirit Bharati has made entirely his own:

Wind, come softly.

Don’t break the shutters of the windows.

Don’t scatter the papers.

Don’t throw down the books on the shelf.

There, look what you did — you threw them all down.

You tore the pages of the books.

You brought rain again.

You’re very clever at poking fun at weaklings.

Frail crumbling houses, crumbling doors, crumbling rafters,

Crumbling wood, crumbling bodies, crumbling lives,

Crumbling hearts —

The wind god winnows and crushes them all.

He won’t do what you tell him.

So, come, let’s build strong homes,

Let’s joint the doors firmly.

Practise to firm the body.

Make the heart steadfast.

Do this, and the wind will be friends with us.

The wind blows out weak fires.

He makes strong fires roar and flourish.

His friendship is good.

We praise him every day. (Translated from the Tamil by A.K. Ramanujan)

Ulisse Lendaro, through the medium of film, is clearly following in this august tradition!

The links between Shelley and India strike me as poorly understood. I was able to locate what seems to be a seminal book by Dr. John G Samuel of the Institute Asian Studies: “Comparative study of the poetry of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792-1822, English Romantic poet, with the poetry of C. Subrahmanya Bharati, 1882-1921, Indian revolutionary poet”. A quick scan of the literature turns up very little in the way of current scholarly investigations of Shelley’s influence on either Tagore or Bharati. Given the current climate in academic romantic circles, this would seem to be a glaring oversight. I welcome my readers to point me in the direction of anything of interest. This is a subject I wish to pursue.

“Creators are at the disposal of humanity to help create a better future. — Ulisse Lendaro ”

Jitendra and Ulisse very kindly provide me with a link to the film's trailer. And I am pleased to be able to share that with you today.

The film is scheduled for release in the new year and I will have many more details which I can provide you with in due course. What I can say is that this is very clearly a work of art that was created in a distinctly Shelleyan revolutionary spirit with great sensitivity and love. The film expressly commemorates the 200th anniversary of the publication of Ode to the West Wind. Human O.A.K. is beautifully scored and the production values are extraordinary — all the more so due to the fact that this was filmed during the pandemic under very difficult circumstances. Ulisse and Jitendra are themselves the embodiment of the revolutionary spirit they so admire in Shelley; a spirit of resistance, resilience, and ultimately renewal. In these difficult times, their film is a breath of fresh air and an inspiration.

“Resistance. Resilience. Renewal.”

Ulisse Lendaro is an Italian director, producer and actor. He received a special mention for his acting from the theater critics at Premio Hystrio in 2004. After appearing for many years in theatrical productions, Lendaro produced a cult horror film directed by Jonathan Zarantonello. In 2017 he directed Imperfect Age, a movie that premiered at the Rome International Film Festival and which was warmly recieved. Produced by Aurora Film and Rai Cinema Imperfect Age was been described by Rolling Stone Magazine as a mix between Black Swan and All about Eve. In 2020 Lendaro directed the short film En Pointe with the participation of Roberto Bolle. The film was entered in the competition at the Giffoni Film Festival in 2020.

https://www.linkedin.com/company/24647461/admin/

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0501764/

https://filmfreeway.com/UlisseLendaro450/photos

Jitendra Mishra is one of the few Indian film producers & promoters who have been able to create a

benchmark in ‘Alternative method of Film Production, Distribution & Promotion’ at international level. Committed towards meaningful cinema, Jitendra has already been associated with the production, distribution and promotion of more than 100 films in different categories in various capacities. Many of them have got worldwide acclamation and recognition in global film festivals like Venice, Cannes, Berlin & Toronto. His recent feature film production ‘The Last Color' has already been selected in more than 50 international film festivals and won 15 awards as of now. The film had a special screening at the prestigious UN

headquarters.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jitendra_Mishra

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm4251856/

A City of Death: The Shelleys and Mont Blanc

In September of 2017 "The Shelley Conference" took place in London, England. It brought together some of the greatest Shelleyans alive, and it introduced to the world a new generation of young scholars brimming with interesting ideas about Mary and Percy. Carl McKeating is one of those young scholars. Carl introduces some startling insights into what and who shaped the impressions the Shelley's formed of Mont Blanc and its environs. Those impressions were to influence some of the most important literature in the western canon: Percy's poem, Mont Blanc and Mary's novel, Frankenstein. Please join Carl for a thrilling, insightful 20 minute excursion to Chamonix in 1816!

Graham with Mont Blanc in the background, 2016.

One of the genuine highlights of the Shelley Conference 2017 was a dynamic presentation by University of Leeds scholar Carl McKeating: "A City of Death: The Shelleys and Mont Blanc." Taking Mary and Percy’s History of a Six Weeks Tour as his focus, McKeating explores what was for me an exciting but hitherto poorly understood aspect of the book: the extent to which Mary’s and Percy’s perceptions of Mont Blanc were influenced and even conditioned by the tour guides they employed.

Carl McKeating.

When I met Carl at the Shelley Conference 2017, I was delighted to discover that we shared a love of the mountains and rock climbing. He has even authored books and articles on the subject. You can learn more about him here. Of his experiences, Carl writes,

I feel my research benefits from the insight offered by a climbing and mountaineering background. I have had a varied career that for the most part has prioritised spending time in mountain ranges. Nonetheless, I momentarily settled down to teach and left my most recent post as a secondary English teacher to commence the PhD at Leeds. I studied at Lancaster University for my undergraduate degree, where the tutorship of the poet Paul Farley was an inspiration for future academic and creative writing.

But before getting to McKeating's great talk (included in audio-visual below), I wanted set the scene a little and share some of my own experiences with a mountain that in some ways can feel a bit anti-climactic after having read all the great literature about it. So, buckle up: we're headed to the Alps!

Mont Blanc seen from Geneva. Copyright Graham Henderson, 2016.

The photograph above provides a view of the Mont Blanc Massif that is identical to that which the Shelleys might have enjoyed from their window in the Hotel d'Angleterre. I say might because the summer the Shelleys spent in Switzerland came to be known as the "Year Without Summer." Cold, dark, rainy - even snowy - the summer of 1816 was exceptionally bad. The unseasonable weather was attributable to a combination of factors. Europe was still in the grips of what today we call the "little ice age". But the conditions were exacerbated by the eruption in 1815 of a massive volcano, Mount Tambora. You can read about it here. It is more likely that the Shelley's saw something like this (perhaps minus the dramatic rainbow!):

View of Mont Blanc Massif, obscured by clouds. Copyright Graham Henderson, 2016.

If you travel to Mont Blanc today, you will have a very different experience from that of the Shelleys, who described the famous Swiss mountain as sublime and infused with supernatural terrors. Today, you can leave Geneva on a modern superhighway and be in your hotel room in just over an hour. Mary and Percy's journey required almost three days on horseback.

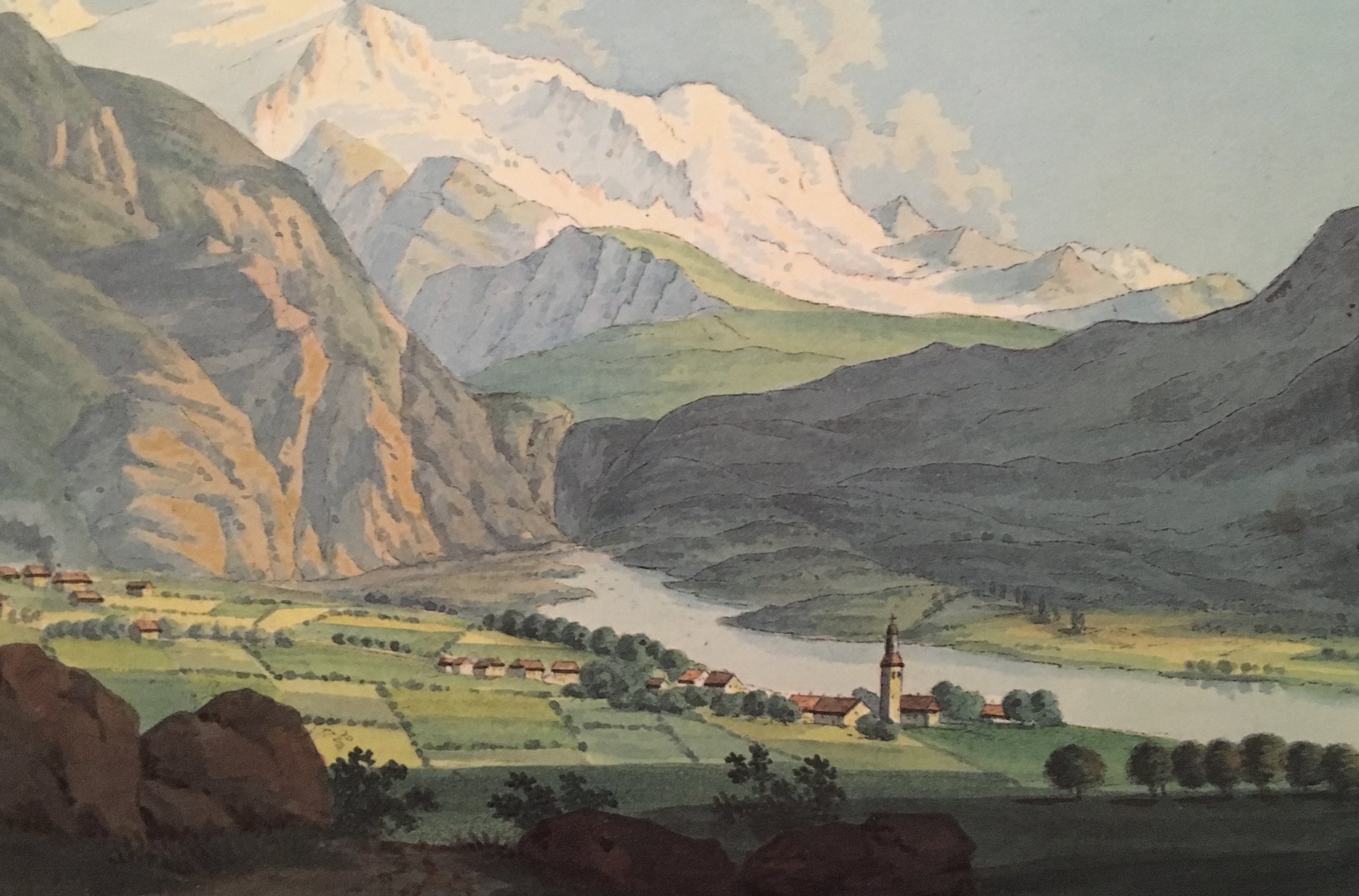

If you wanted to avoid the superhighways and follow the footsteps of the Shelleys instead, you follow the old “Imperial Highway” which takes you through Servox (not shown on the map above). The first part of the journey is through wide open, picturesque countryside with no hint of sublimity. Here is what it would have looked like to the Shelleys when they reached the environs of Bonneville just south of Geneva:

Gabriel Charton, "Saint-Martin". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015

However, the further you go, the more intimations there are of what is to come. For example, I stopped near Oex and walked to the base of the Cascade de l'Arpenaz. Percy Shelley wrote about this place in his letter to Thomas Love Peacock on 22 July 1816. You should carefuly compare it with the image to the right to see how startling accurate Percy's description is:

Cascade de l'Arpenaz. Copyright Henderson

"They were no more than mountain rivulets, but the height from which they fell, at least of twelve hundred feet, made them assume a character inconsistent with the smallness of their stream. The first [i.e. the Arpenaz waterfall] fell from the overhanging brow of a black precipice on an enormous rock, precisely resembling some colossal Egyptian deity. It struck the head of the visionary image, and gracefully dividing there, fell from it in folds of foam more like to cloud than water, imitating a veil of the most exquisite woof. It then united, concealing the lower part of the statue, and hiding itself in a winding of its channel, burst into a deeper fall, and crossed our route in its path towards the Arve."

From there I continued on the Imperial Highway to Servoz. The road climbs up on the shoulder of the valley north of the ravine, reaching a considerable height at Servoz which today is a gorgeous little village where properties are on sale for almost USD $2,000,000. When Shelley visited, it was little more than a hamlet. After Servoz, the road then descends to the valley floor and the valley narrows dramatically. It would have looked like this to Shelley. You can see the ravine of the Arve in the middle distance:

Gabriel Charton, "Servox". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015. The church is still there.

Shortly after you enter this gorge, the river suddenly (and famously) makes a sharp turn to the left which dramatically reveals the Mont Blanc Massif in all of its majesty. Here is what Shelley wrote:

"As we proceeded, our route still lay through the valley, or rather, as it had now become, the vast ravine, which is at once the couch and the creation of the terrible Arve. We ascended, winding between mountains whose immensity staggers the imagination. We crossed the path of a torrent, which three days since had descended from the thawing snow, and torn the road away... From Servoz three leagues remain to Chamouni.—Mont Blanc was before us—the Alps, with their innumerable glaciers on high all around, closing in the complicated windings of the single vale—forests inexpressibly beautiful, but majestic in their beauty—intermingled beech and pine, and oak, overshadowed our road, or receded, whilst lawns of such verdure as I have never seen before occupied these openings, and gradually became darker in their recesses. Mont Blanc was before us, but it was covered with cloud; its base, furrowed with dreadful gaps, was seen above. Pinnacles of snow intolerably bright, part of the chain connected with Mont Blanc, shone through the clouds at intervals on high. I never knew—I never imagined what mountains were before. The immensity of these aerial summits excited, when they suddenly burst upon the sight, a sentiment of extatic wonder, not unallied to madness. And remember this was all one scene, it all pressed home to our regard and our imagination. Though it embraced a vast extent of space, the snowy pyramids which shot into the bright blue sky seemed to overhang our path; the ravine, clothed with gigantic pines, and black with its depth below, so deep that the very roaring of the untameable Arve, which rolled through it, could not be heard above—all was as much our own, as if we had been the creators of such impressions in the minds of others as now occupied our own. Nature was the poet, whose harmony held our spirits more breathless than that of the divinest."

When I arrived in the valley, I encountered the same problem that bedeviled the Shelleys -- Mont Blanc was shrouded with clouds.

The Vale of Chamonix, 2016. Copyright Henderson.

One thing that the modern traveler misses is the thundering of the Arve. The modern roads are far removed from the river and the roar of traffic obscures that of the river itself. One other thing I can tell you is this – pictures do the valley absolutely no justice whatsoever. No picture I have ever seen conveys the manner in which the mountains seem to, as Shelley notes, “overhang” the valley floor. Here is a contemporary painting which offers a view the Shelleys would not have seen because they did not travel to the Col de Voza:

Gabriel Charton, "Le Col de Voza." From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015

Mont Blanc is not even in the picture; it is off to the right. In the foreground, you can see the Glacier des Bossons. Just beyond it lies the spire of the church in Chamonix and then the terminus of the Mer de Glace, which you can see actually encroaches on the valley floor itself. Today these glaciers have long since receded into the mountains.

It is a point worth making that for travelers in the early 19th century, even for those such as the Shelleys who had never seen the Alps, there is an aura of the picturesque that infuses the valley – not the sublime. In other words, the landscape around Mont Blanc is ruggedly beautiful, rather than overwhelmingly powerful, a quality we do find in Shelley's great poem "Mont Blanc." While they were in the valley, the Shelleys had difficulty actually seeing Mont Blanc – and this is not at all unusual. A cloud deck seems to perpetually overhang the valley. But even when you can see it, the mountain is not exactly imposing in-and-of-itself. Here is a photo I took a couple of years back that will give you a better idea of this:

Mont Blanc Massif from Chamonix. Copyright Henderson, 2016.

Mont Blanc is not the sharp peak the left. Nor is it the one on the right. In fact, it is the subtle summit set back from the rest almost dead center of the photograph. Trust me, it does not in-and-of-itself inspire the feelings of awe and dread we encounter in Shelley's poem bearing the mountain's name. It is not at all evident that it is even the tallest mountain. In fact, the reverse seems to be true. The Aguile de Midi looms precipitously above your head in Chamonix – Mont Blanc is a distant and altogether benign presence. Not like Mount Everest, for example. I have stood at North Face Base Camp – and let me tell you, up close Mount Everest looks like a stone-cold killer:

North Face of Mount Everest from Rongbuk. Copyright Henderson, 1994.

There is no doubt that the Shelleys’ minds would have been very much more impressionable than ours are today – and less inured to wild landscapes. They had never actually seen real mountains. Very few travel guides existed that could prepare you for what you were about to see. As I mentioned before, in the 1810s, the Mont Blanc glaciers actually spilled out onto the valley and were menacingly advancing (for an idea of how this might have looked to the Shelleys, see the image below). The Shelleys were also fresh from their stay at the Villa Diodati where they had engaged in a ghost-story competition! Then there was the outlandish weather that was the hallmark of the “Year Without Summer”. All of this may well have perhaps primed then for, shall we say, a heightened experience.

Gabriel Charton, "La Source de l'Arvenon". From Souvenirs Pittoresques des Glaciers de Chamouny, 1821; reprinted by Tony Astil, 2015.

The glacier can not even be seen from Montanvert. It is around the corner having retreated 10 miles thanks to climate change- why am I smiling!? Copyright Henderson, 2016.

This leaves us with an obvious dilemma: if the mountain is somewhat unremarkable, why do the Shelleys write about it as if it were the most imposing, threatening presence in the Alps? This is where Carl McKeating picks up the story, for as he tells us, there was another factor which led to the Shelley’s highly emotional response to what they saw: they were powerfully influenced by their tour guides. As McKeating points out, critics have rarely viewed the Shelleys as tourists, but this is exactly what they were. In fact, in several instances, Percy bluntly complains about the presence of other tourists – demonstrating that the more things change, the more they stay the same!

Both Mary and Percy frame Mont Blanc as a place where supernatural forces lurked and where death was imminent. References to Mont Blanc as the abode of witches appears in Byron’s Manfred, Mary’s Frankenstein and Percy’s "Mont Blanc." Percy at one point records witnessing an avalanche -- in July 1816. McKeating speculates on the role the guides might have played at such a moment. While their duty was to keep the guests safe, they also wanted to take tourists to the most exciting places – places which also might involve an experience of danger.

The guides also regaled their charges with folklore and wild tales. McKeating suggests that much of what we read in the accounts of Mary and Percy is derived directly from stories they were told. Mary often begins an episode with the words, “our guide told us a story….”

McKeating also notes how Percy’s impression of Mont Blanc radically evolved over an extremely short period of time. Before he left, Percy had written to Byron referring to the mountains as “palaces of nature.” By the time he wrote about them in his great poem, they had become “palaces of death.”

McKeating is also one of the most entertaining presenters I have ever seen inside or outside of the academy. You will thank me if you take my advice and spend 20 minutes with him while he spins his own tale of mystery, intrigue, witches......and the palace of death!!!

You can visit Carl's profile here. And this is an overview of the research Carl is undertaking at the University of Leeds:

Mont Blanc was a towering presence in the imaginative geography of British eighteenth and early nineteenth century writing, featuring in poetry, fiction, travel literature, and natural philosophy. My work uses a broadly chronological and geocritical approach to investigate the cultural prominence of Western Europe's highest mountain. The period of my study addresses the 'discovery' of Mont Blanc by William Windham's party of 'Eight Englishmen' in 1741, Mont Blanc's first ascent by the Horace Benedict de Saussure-sponsored Paccard and Balmat in 1786, and the mountain's literary blossoming during the Romantic period when it played a key role in the re-evaluation of mountain topography and the formation of identity for British writers including William Wordsworth, Helen Maria Williams, Mary Robinson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Shelley, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

- A Philosophical View of Reform

- Address on the Death of Princess Charlotte

- Adonais

- Alastor

- Anna Mercer

- Anna Valle

- Byron

- Carl McKeating

- Chamonix

- Ciaran O'Rourke

- Coleridge

- Defense of Poetry

- Earl Wasserman

- Edward Trelawney

- Engels

- Frankenstein

- G. John Samuel

- Gabriel Charton

- Gandhi

- Heidi Thompson

- Hellas

- Hymn Before Sunrise

- James Bieri

- James Connolly

- Jitendra Mishra

- Joseph Severn

- Keats Foundation

- Kelvin Everest

- Larry Henderson

- Manfred

- Mary Shelley

- Mask of Anarchy

- Michael O'Neill

- Michael Scrivener

- Mont Blanc

- Nora Crook

- Ode to the West Wind

- On Christianity

- On Life

- Pandemic

- Paul Foot

- PMS Dawson

- Prometheus Unbound

- Protestant Cemetery

- Queen Mab

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Roland Duerksen

- Rome

- Shelley Conference 2017

- Sir william Drummond

- Skepticism

- Stuart Curran

- Subramania Bharati

- The Cenci

- The Cloud

- The Shelley Conference 2017

- The Sublime

- To Jane With a Guitar

- Tom Mole

- Triumph of Life

- Ulisse Lendaro

- Ursula K Le Guin

- Victorian Literature

- When the Lamp is Shattered

- William Bell Scott