Jon Kerr's Tuesday Verse

Selections of Shelley’s Poetry & Prose

Tuesday Verse is a new feature of The Real Percy Bysshe Shelley that brings you close to his poetry and, occasionally, prose. Each Tuesday we will deliver to you a poem or excerpt of a poem which Romantic scholar Jon Kerr will offer some brief thoughts about. Jon will also pair the offering with an image that may offer some context. We welcome suggestions for future posts as well as your own ideas about what you think Shelley is trying to accomplish with his verse. Enjoy!!

Jon is a recently graduated from the University of Toronto with his PhD in English literature with a specialization in the Romantics. He is currently at Mount Alison University in New Brunswick, Canada on a post doc fellowship.

PB Shelley, “To S and C” (1819-20)

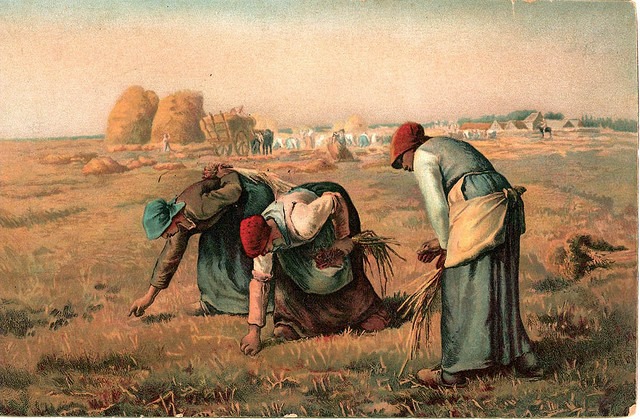

In 1820, Shelley began toying with the idea of publishing (as he put it) “a little volume of popular songs wholly political & destined to awaken & direct the imagination of the reformers.” As with other poems to be included in this collection, “To S. and C.” confronts some of the major events of the day with a bouncy, catchy rhythm, and it offers instruction through a collection of straightforward but powerful similes. Such a style of writing seems to affirm the view that England’s common people, and not just educated elites, have a part to play in the country’s reform movements.

P.B. Shelley, “Ode to Liberty” (1820)

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Men of England”

In Europe’s revolutionary era, the contest over hearts and minds was fought across many cultural arenas. We get a sense of this in “Men of England,” a poem written in the style of the popular songs that, in the England of Shelley’s day, would have been the stuff of riotous sing-alongs in pubs, fairs, and other centres of public life.

P.B. Shelley, “A New National Anthem” (1819 or 1820)

P.B. Shelley, “Sonnet: Political Greatness” (1820 or 1821)

P.B. Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" (1819)

Percy Shelley, “Love’s Philosophy”

A cheeky seduction poem, “Love’s Philosophy” gives us a speaker who attempts to use his arts to capture the heart (and perhaps more) of a love interest: “look around at the world,” he says to his unnamed lover. “Everywhere, you see things coming together, unifying in matter and spirit. Isn’t it a crime against our nature not to do the same?”

However, the poem doesn’t just showcase Shelley’s playful side. It demonstrates the immense influence that all things natural had on many writers of this time.

PB Shelley, Preface to Frankenstein

The Preface to Frankenstein—written by Percy, oddly enough—brings us back to the now legendary moment of inspiration that gave us Mary Shelley’s famous novel: vacationing at Lake Geneva with a circle of friends and fellow writers, the Shelleys are confined indoors due to inclement weather. Reading German horror stories by candlelight, the crew eventually settles on a competition proposed by Lord Byron. The competition is simple: who can write the best horror story? In the months and years ahead, Byron and Percy—the two literary heavyweights of the party—lose interest and take up other projects; Mary, meanwhile, sets to work on what will become Frankenstein, one of the most celebrated English novels of all time.

P.B. Shelley, “To the Lord Chancellor”

As American’s go to the polls today in a series of epochal mid-term elections, Shelley’s To the Lord Chancellor seems a more than appropriate choice for our Tuesday Verse selection. As Timothy Webb once noted, politics was perhaps the consuming passion of Shelley’s life. On the 6 November 1819, right around the time he might have been writing this poem, Shelley wrote to his friends the Gisbornes saying, “I have deserted the odorous gardens of literature to journey across the great sandy desert of Politics; not, you may imagine, without the hope of finding some enchanted paradise.” Shelley was what was known as a perfectibilist, someone who believed in the perfectibility of humans. He even developed a sophisticated political and social theory to compliment this belief. This does NOT mean Shelley was a utopian - he emphatically was not. But he did believe in the gradual evolution of the human species toward something like perfection.

“Time” by Percy Bysshe Shelley

In his life and writings, Shelley was fascinated with the element—water—that would one day take his life. In the above poem, Shelley explores another subject, “time,” by linking it to the great waterways of the world.

P.B. Shelley, "Ozymandias" (1817)

The product of a friendly writing competition between Shelley and his friend Horace Smith, the sonnet “Ozymandias” presents us with a striking image: a hulking, shattered, and half-buried statue of Ozymandias, better known as Ramses II, the famed Egyptian pharaoh

William Blake, "The Tyger" (1794)

Blake’s “Tyger” is a classic of British Romantic poetry, one we couldn’t resist branching out to explore for this week’s Tuesday Verse. Blake’s poem marvels at the tiger, a sublime creature for its ability to excite both awe and terror. However, Blake is equally attracted to the shadowy figure who, hunched over his anvil, forges into being this majestic apex predator, as if from steel and fire. What kind of prime creator, Blake wonders, could have brought to life such a creature, perfect in its killing ability?

P.B. Shelley, "Sonnet: Ye Hasten to the Grave"

In England, the sonnet has often been used to explore themes of transience, death, and immortality. Shelley's "Ye Hasten to the Grave" continues this trend; however, it does so by refocusing attention away from contemplation about death and the afterlife and back toward the pleasures of life in the here-and-now. Shelley partly frames his sonnet as a series of rhetorical questions for the kind of person who seeks to embrace death as part of his or her religious convictions. For such a person, of course, death is not the end of life but rather life's transformation into something new and blissful. In keeping with his atheism, Shelley implies that the belief in such an afterlife is a form of misdirected hope stemming from hubris or conventional thinking (what Shelley calls "the world's livery"). But perhaps worst of all, in seeking out "a refuge in the cavern of grey death," such a person flees not only life's pain but also its pleasure, the "green and pleasant path" that suggests a power and beauty in life's here-and-now.

Even so, it's worth considering that Shelley's poem doesn't actually affirm very much. Even though his position is atheistical, Shelley has given us a poem more interested in asking questions (about life, death, and belief) rather than averring a new doctrine.

P.B. Shelley, "An Exhortation" (1820)

In "An Exhortation," Shelley addresses a question that preoccupied his age: what is a poet? In attempting to answer this question, Shelley uses as his primary metaphor the chameleon, the shape-shifting, colour-adjusting reptile. Readers of the Romantics might know that, funny enough, the chameleon was also central to Keats' understanding of the poet. According to Keats, the poet's distinguishing trait was their ability to write convincingly of any life situation, event, or mindset, an (adapt)ability that stemmed from their deep knowledge of human nature.

P.B. Shelley, from "Julian and Maddalo" (1818-19)

“Julian and Maddalo” is a conversation poem that centres on the relationship between two figures: the aristocratic Maddalo (who resembles Shelley’s friend and fellow poet Lord Byron) and Julian (an idealist who closely resembles Shelley himself). Throughout the poem, the conversations and experiences of the two compatriots touch on subjects that preoccupied both Shelley and Byron in their life and writing. Julian argues for the mind’s power to change itself and the world around it. The far more skeptical Maddalo calls this “Utopian.” The will is not free, says Maddalo; rather, our lives are shaped by forces beyond our control.

P.B. Shelley, “The Flower that Smiles Today” (1821-22)

Likely written in the final year or so of his life, “The Flower that Smiles Today” captures Shelley’s increasing preoccupation with the transience of life and its joys. The final years of Shelley’s life were marked by increasing difficulties, both personal and political: between 1816 and 1819, Shelley and Mary had lost three children, which brought growing strain to their marriage; at the early 1820s came with a series of critical setbacks to England’s reform movement that, just a few years prior, seemed on the verge of creating real change in the country. These issues hang over Shelley’s mutability poems like this one, which ponders how it is possible to survive particular joys—friendship, love, beauty—once we know we can never experience them again.

Some of you might also notice connections, both stylistic and thematic, with some of Byron’s poetry, which often ponders similar questions. Both the Byronic hero and the speaker of Shelley’s poem capture the zeitgeist of Britain’s revolutionary period as it gradually drew to a close: that is, both reflect upon the disappointed hopes that come to people (and societies) that once seemed destined to achieve great things.

P.B. Shelley, “Lines Written During the Castlereagh Administration” (1819-20)

P.B. Shelley, “Mask of Anarchy” (1819)

“The Mask of Anarchy” begins on an unassuming note: Shelley’s claim that his “visions of Poesy” have come to him in a dream might lead the reader to imagine that what follows is a flight into imaginative wonder and away from reality. But as with “Queen Mab,” Shelley’s dream vision does not take us away from the world but forces us to confront its ugliest features. Alluding to the four horsemen of the apocalypse described in the Book of Revelations, the opening of “The Mask of Anarchy” presents four figures who, according to Shelley, were undertaking their own world-destroying fury: Murder, Fraud, Hypocrisy, and Anarchy. Unlike in Revelations, however, these are not abstract forces in a spiritual conflict between good and evil. Shelley gives his evil corporeal form and well-recognized names: Viscount Castlereagh; Lord Eldon; Lord Sidmouth; and the royalty, churchmen, and timeservers of Britain’s establishment class. If the apocalypse is coming, in other words, it will be achieved through Britain’s unholy trinity of “God, and King, and Law.”

In 1819, it might very well have felt like the apocalypse was coming: food shortages, economic turmoil, and widespread civil unrest plagued the realm. But Shelley’s poem also registers some hope. If poets are prophetic figures whose deep knowledge of their times creates knowledge and permits change (ideas explored in the essay “Defense of Poetry”), then Shelley’s dream vision might produce “the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time”—a different, brighter future, in other words.

P.B. Shelley, from “A Defense of Poetry” (1821)